The Bretton Woods Agreement called for each currency’s value to be fixed relative to other currencies. The mechanism for maintaining these rates, however, was to be intervention by governments and central banks in the currency market.

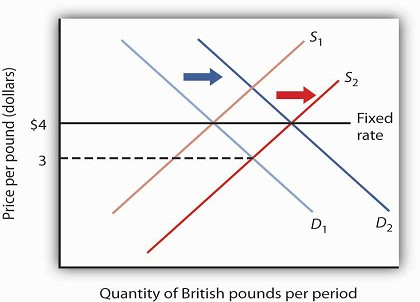

Again suppose that the exchange rate between the dollar and the British pound is fixed at $4 per £1. Suppose further that this rate is an equilibrium rate, as illustrated in Figure 30.5. As long as the fixed rate coincides with the equilibrium rate, the fixed exchange rate operates in the same fashion as a free-floating rate.

Initially, the equilibrium price of the British pound equals $4, the fixed rate between the pound and the dollar. Now suppose an increased supply of British pounds lowers the equilibrium price of the pound to $3. The Bank of England could purchase pounds by selling dollars in order to shift the demand curve for pounds to D2. Alternatively, the Fed could shift the demand curve to D2 by buying pounds.

Now suppose that the British choose to purchase more U.S. goods and services. The supply curve for pounds increases, and the equilibrium exchange rate for the pound (in terms of dollars) falls to, say, $3. Under the terms of the Bretton Woods Agreement, Britain and the United States would be required to intervene in the market to bring the exchange rate back to the rate fixed in the agreement, $4. If the adjustment were to be made by the British central bank, the Bank of England, it would have to purchase pounds. It would do so by exchanging dollars it had previously acquired in other transactions for pounds. As it sold dollars, it would take in checks written in pounds. When a central bank sells an asset, the checks that come into the central bank reduce the money supply and bank reserves in that country. We saw in the chapter explaining he money supply, for example, that the sale of bonds by the Fed reduces the U.S. money supply. Similarly, the sale of dollars by the Bank of England would reduce the British money supply. In order to bring its exchange rate back to the agreed-to level,

Britain would have to carry out a contractionary monetary policy.

Alternatively, the Fed could intervene. It could purchase pounds, writing checks in dollars. But when a central bank purchases assets, it adds reserves to the system and increases the money supply. The United States would thus be forced to carry out an expansionary monetary policy.

Domestic disturbances created by efforts to maintain fixed exchange rates brought about the demise of the Bretton Woods system. Japan and West Germany gave up the effort to maintain the fixed values of their currencies in the spring of 1971 and announced they were withdrawing from the Bretton Woods system. President Richard Nixon pulled the United States out of the system in August of that year, and the system collapsed. An attempt to revive fixed exchange rates in 1973 collapsed almost immediately, and the world has operated largely on a managed float ever since.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the United States had redeemed dollars held by other governments for gold; President Nixon terminated that policy as he withdrew the United States from the Bretton Woods system. The dollar is no longer backed by gold. Fixed exchange rate systems offer the advantage of predictable currency values—when they are working. But for fixed exchange rates to work, the countries participating in them must maintain domestic economic conditions that will keep equilibrium currency values close to the fixed rates. Sovereign nations must be willing to coordinate their monetary and fiscal policies. Achieving that kind of coordination among independent countries can be a difficult task.

The fact that coordination of monetary and fiscal policies is difficult does not mean it is impossible. Eleven members of the European Union not only agreed to fix their exchange rates to one another, they agreed to adopt a common currency, the euro. The new currency was introduced in 1998 and became fully adopted in 1999. Since then, four other nations have joined. The nations that have adopted it have agreed to strict limits on their fiscal policies. Each will continue to have its own central bank, but these national central banks will operate similarly to the regional banks of the Federal Reserve System in the United States. The new European Central Bank will conduct monetary policy throughout the area. Details of this revolutionary venture are provided in the accompanying Case in point.

When exchange rates are fixed but fiscal and monetary policies are not coordinated, equilibrium exchange rates can move away from their fixed levels. Once exchange rates start to diverge, the effort to force currencies up or down through market intervention can be extremely disruptive. And when countries suddenly decide to give that effort up, exchange rates can swing sharply in one direction or another. When that happens, the main virtue of fixed exchange rates, their predictability, is lost.

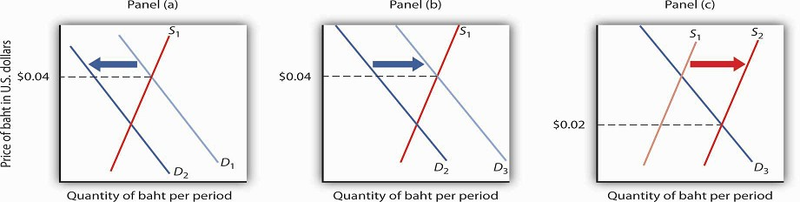

Thailand’s experience with the baht illustrates the potential difficulty with attempts to maintain a fixed exchange rate. Thailand’s central bank had held the exchange rate between the dollar and the baht steady, at a price for the baht of $0.04. Several factors, including weakness in the Japanese economy, reduced the demand for Thai exports and thus reduced the demand for the baht, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 30.6. Thailand’s central bank, committed to maintaining the price of the baht at $0.04, bought baht to increase the demand, as shown in Panel (b). Central banks buy their own currency using their reserves of foreign currencies. We have seen that when a central bank sells bonds, the money supply falls. When it sells foreign currency, the result is no different. Sales of foreign currency by Thailand’s central bank in order to purchase the baht thus reduced Thailand’s money supply and reduced the bank’s holdings of foreign currencies. As currency traders began to suspect that the bank might give up its effort to hold the baht’s value, they sold baht, shifting the supply curve to the right, as shown in Panel (c). That forced the central bank to buy even more baht—selling even more foreign currency until it finally gave up the effort and allowed the baht to become a free-floating currency. By the end of 1997, the baht had lost nearly half its value relative to the dollar.

Weakness in the Japanese economy, among other factors, led to a reduced demand for the baht (Panel [a]). That put downward pressure on the baht’s value relative to other currencies. Committed to keeping the price of the baht at $0.04, Thailand’s central bank bought baht to increase the demand, as shown in Panel (b). However, as holders of baht and other Thai assets began to fear that the central bank might give up its effort to prop up the baht, they sold baht, shifting the supply curve for baht to the right (Panel [c]) and putting more downward pressure on the baht’s price. Finally, in July of 1997, the central bank gave up its effort to prop up the currency. By the end of the year, the baht’s dollar value had fallen to about $0.02.

As we saw in the introduction to this chapter, the plunge in the baht was the first in a chain of currency crises that rocked the world in 1997 and 1998. International trade has the great virtue of increasing the availability of goods and services to the world’s consumers. But financing trade—and the way nations handle that financing—can create difficulties.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In a free-floating exchange rate system, exchange rates are determined by demand and supply.

- Exchange rates are determined by demand and supply in a managed float system, but governments intervene as buyers or sellers of currencies in an effort to influence exchange rates.

- In a fixed exchange rate system, exchange rates among currencies are not allowed to change. The gold standard and the Bretton Woods system are examples of fixed exchange rate systems.

TRY IT!

Suppose a nation’s central bank is committed to holding the value of its currency, the mon, at $2 per mon. Suppose further that holders of the mon fear that its value is about to fall and begin selling mon to purchase U.S. dollars. What will happen in the market for mon? Explain your answer carefully, and illustrate it using a demand and supply graph for the market for mon. What action will the nation’s central bank take? Use your graph to show the result of the central bank’s action. Why might this action fuel concern among holders of the mon about its future prospects? What difficulties will this create for the nation’s central bank?

Case in Point: The Euro

It marks the most dramatic development in international finance since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. A new currency, the euro, began trading among 11 European nations—Austria,

Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain —in 1999. During a three-year transition, each nation continued to have its own currency,

which traded at a fixed rate with the euro. In 2002, the urrencies of the participant nations disappeared altogether and were replaced by the euro. In 2007, Slovenia dopted the euro, as did

Cyprus and Malta in 2008 and Slovakia in 2009. Several other countries are also hoping to join. Notable exceptions are Britain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Denmark. Still, most of Europe now

operates as the ultimate fixed exchange rate regime, a region with a single currency.

To participate in this radical experiment, the nations switching to the euro had to agree to give up considerable autonomy in monetary and fiscal policy. While each nation continues to have

its own central bank, those central banks operate more like regional banks of the Federal Reserve System in the United States; they have no authority to conduct monetary policy. That

authority is vested in a new central bank, the European Central Bank.

The participants have also agreed in principle to strict limits on their fiscal policies. Their deficits can be no greater than 3% of nominal GDP, and their total national debt cannot exceed

60% of nominal GDP.

Whether sovereign nations will be able—or willing—to operate under economic restrictions as strict as these remains to be seen. Indeed, several of the nations in the eurozone have exceeded

the limit on national deficits.

A major test of the euro coincided with its 10th anniversary at about the same time the 2008 world financial crisis occurred. It has been a mixed blessing in getting through this difficult

period. For example, guarantees that the Irish government made concerning bank deposits and debt have been better received, because Ireland is part of the euro system. On the other hand, if

Ireland had a floating currency, its depreciation might enhance Irish exports, which would help Ireland to get out of its recession.

The 2008 crisis also revealed insights into the value of the euro as an international currency. The dollar accounts for about two-thirds of global currency reserves, while the euro accounts

for about 25%. Most of world trade is still conducted in dollars, and even within the eurozone about a third of trade is conducted in dollars. One reason that the euro has not gained more on

the dollar in terms of world usage during its first 10 years is that, whereas the U.S. government is the single issuer of its public debt, each of the 16 separate European governments in the

eurozone issues its own debt. The smaller market for each country’s debt, each with different risk premiums, makes them less liquid, especially in difficult financial times.

When the euro was launched it was hoped that having a single currency would nudge the countries toward greater market flexibility and higher productivity. However, income per capita is about

at the same level in the eurozone as it was 10 years ago in comparison to that of the United States—about 70%.

Source: “Demonstrably Durable: The Euro at Ten,” Economist, January 3, 2009, p. 50–52.

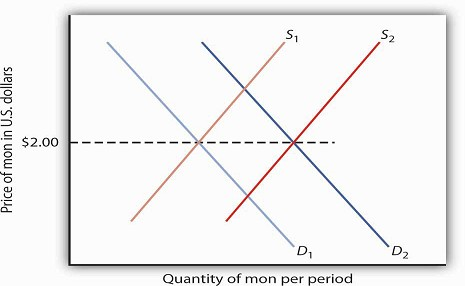

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

The value of the mon is initially $2. Fear that the mon might fall will lead to an increase in its supply to S2, putting downward pressure on the currency. To maintain the value of the mon at

$2, the central bank will buy mon, thus shifting the demand curve to D2. This policy, though, creates two difficulties. First, it requires that the bank sell other currencies, and a sale of

any asset by a central bank is a contractionary monetary policy. Second, the sale depletes the bank’s holdings of foreign currencies. If holders of the mon fear the central bank will give up

its effort, then they might sell mon, shifting the supply curve farther to the right and forcing even more vigorous action by the central bank.

- 3177 reads