The 1970s put Keynesian economics and its prescription for activist policies on the defensive. The period lent considerable support to the monetarist argument that changes in the money supply were the primary determinant of changes in the nominal level of GDP. A series of dramatic shifts in aggregate supply gave credence to the new classical emphasis on long-run aggregate supply as the primary determinant of real GDP. Events did not create the new ideas, but they produced an environment in which those ideas could win greater support.

For economists, the period offered some important lessons. These lessons, as we will see in the next section, forced a rethinking of some of the ideas that had dominated Keynesian thought. The experience of the 1970s suggested the following:

- The short-run aggregate supply curve could not be viewed as something that provided a passive path over which aggregate demand could roam. The short-run aggregate supply curve could shift in ways that clearly affected real GDP, unemployment, and the price level.

- Money mattered more than Keynesians had previously suspected. Keynes had expressed doubts about the effectiveness of monetary policy, particularly in the face of a recessionary gap. Work by monetarists suggested a close correspondence between changes in M2 and subsequent changes in nominal GDP, convincing many Keynesian economists that money was more important than they had thought.

- Stabilization was a more difficult task than many economists had anticipated. Shifts in aggregate supply could frustrate the efforts of policy makers to achieve certain macroeconomic goals.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Beginning in 1961, expansionary fiscal and monetary policies were used to close a recessionary gap; this was the first major U.S. application of Keynesian macroeconomic policy.

- The experience of the 1960s and 1970s appeared to be broadly consistent with the monetarist argument that changes in the money supply are the primary determinant of changes in nominal GDP.

- The new classical school’s argument that the economy operates at its potential output implies that real GDP is determined by long-run aggregate supply. The experience of the 1970s, in which changes in aggregate supply forced changes in real GDP and in the price level, seemed consistent with the new classical economists’ arguments that focused on aggregate supply.

- The experience of the 1970s suggested that changes in the money supply and in aggregate supply were more important determinants of economic activity than many Keynesians had previously thought.

TRY IT!

Draw the aggregate demand and the short-run and long-run aggregate supply curves for an economy operating with an inflationary gap. Show how expansionary fiscal and/or monetary policies would affect such an economy. Now show how this economy could experience a recession and an increase in the price level at the same time.

Case in Point: Tough Medicine

The Keynesian prescription for an inflationary gap seems simple enough. The federal government applies contractionary fiscal policy, or the Fed applies contractionary monetary policy, or

both. But what seems simple in a graph can be maddeningly difficult in the real world. The medicine for an inflationary gap is tough, and it is tough to take.

President Johnson’s new chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Gardner Ackley, urged the president in 1965 to adopt fiscal policies aimed at nudging the aggregate demand curve back to

the left. The president reluctantly agreed and called in the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, the committee that must initiate all revenue measures, to see what he thought of

the idea. Wilbur Mills flatly told Johnson that he wouldn’t even hold hearings to consider a tax increase. For the time being, the tax boost was dead.

The Federal Reserve System did slow the rate of money growth in 1966. But fiscal policy remained sharply expansionary. Mr. Ackley continued to press his case, and in 1967 President Johnson

proposed a temporary 10% increase in personal income taxes. Mr. Mills now endorsed the measure. The temporary tax boost went into effect the following year. The Fed, concerned that the tax

hike would be too contractionary, countered the administration’s shift in fiscal policy with a policy of vigorous money growth in 1967 and 1968.

The late 1960s suggested a sobering reality about the new Keynesian orthodoxy. Stimulating the economy was politically more palatable than contracting it. President Kennedy, while he was not

able to win approval of his tax cut during his lifetime, did manage to put the other expansionary aspects of his program into place early in his administration. The Fed reinforced his

policies. Dealing with an inflationary gap proved to be quite another matter. President Johnson, a master of the legislative process, took three years to get even a mildly contractionary tax

increase put into place, and the Fed acted to counter the impact of this measure by shifting to an expansionary policy.

The second half of the 1960s was marked, in short, by persistent efforts to boost aggregate demand, efforts that kept the economy in an inflationary gap through most of the decade. It was a

gap that would usher in a series of supply-side troubles in the next decade.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

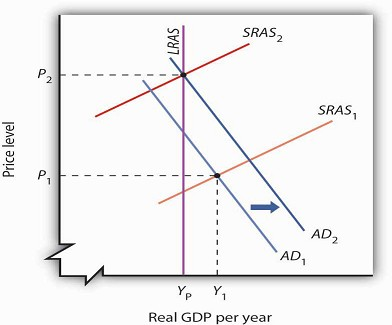

Even with an inflationary gap, it is possible to pursue expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, shifting the aggregate demand curve to the right, as shown. The inflationary gap will,

however, produce an increase in nominal wages, reducing short-run aggregate supply over time. In the case shown here, real GDP rises at first, then falls back to potential output with the

reduction in short-run aggregate supply.

- 1645 reads