note: This module has been peer-reviewed, accepted, and sanctioned by the National Council of the Professors of Educational Administration (NCPEA) as a scholarly contribution to the knowledge base in educational administration.

As technology expands the professional development available outside the traditional classroom, it is important that educational executives consider the role of distance education in the development of school leaders. The student population has changed with many older adults, particularly school administrators attending universities and urging the universities to provide instruction in more convenient ways. More districts are seeking to develop leadership in their districts through customized leadership programs. “Working adults want education delivered direct to them, at home or the workplace . . Preparation may be weaker than among conventional students; motivation may be stronger” (Jones & Pritchard, 1999, p. 56).

These new methods of delivery include television and the Internet, both of which allow students to access coursework miles from the traditional campus classroom. Instruction will have to change and assignments will need to be more tailored to a population that is not on campus. College instructors will increasingly encounter classes that are much larger than the traditional graduate level class. Decisions regarding which courses are selected for distance education need to be carefully considered. As Lamb and Smith (2000) pointed out, “The distance education environment tends to exaggerate both the positive and the negative aspects of all the elements of instruction” (p. 13). Kelly (1990) noted that instructors must develop new skills for distance education teaching in the areas of timing, teaching methods, feedback from students at remote sites, and the evaluation of students.

Stammen (2001) noted that technologies in and of themselves do not change the nature of leadership but the way educators use the technology does. The new technology requires instructors to re-consider and develop additional learner centered environments. To make learning happen instructors need to understand both how to work the content and how the technology is impacting their instruction. Some are skeptical of university motives noting the prospect of not having to build new facilities to accommodate more students has great economic appeal (Weigel, 2000). Regardless, the opportunity to improve the instruction and availability through the new technology is here to stay.

It is important to determine the effectiveness of the new methods of delivery and periodically compare them to traditional campus classroom instruction. Swan and Jackman (2000) discussed Souder's 1993 comparison of distance learners with traditional learners, stating that the distance learning students “performed better than the host-site learners in several areas or fields of study, including exams and homework assignments” (p. 59). Citing the limited number of studies comparing different methods of instruction in higher education, Swan and Jackson looked at remote-site and home-site students at the secondary school level. They found no significant differences in student achievement between the two sites when comparing grade point averages.

Methodology

In 2002, educational leadership students in our school finance class and school principalship classes at Ball State University were surveyed (Sharp & Cox, 2003). Of these students, 12 in the finance class were in a studio classroom, with 89 taking the course on television at 42 off-campus sites around the state of Indiana. In the principalship course, 25 students were in the studio and 60 were at 22 remote television sites. In 2004, when one of the professors had moved to the University of South Carolina, we again surveyed our distance learning classes. This time, we had 75 students in the school finance television class and seven in the studio class at Ball State. At South Carolina, we had 64 in the televised sections of school law and leadership theory and 35 students in the studio sections of those courses. The purpose of the identical surveys in both years was to see if there were differing points of view regarding the questioning format, attendance, and assessment procedures between the studio groups and the groups at the remote sites and whether there were any changes in opinion between the survey conducted in 2002 and the one done in 2004. We also wanted to collect data regarding any technological problems and information about the students themselves and their backgrounds.

The survey for the research study was added to an evaluation form so that all students would complete the survey. The results were not given to us until after final grades were submitted. Proctors at the remote sites distributed surveys to the students to complete onsite and then mailed them back to the office for scoring. Thus, every student in attendance completed a survey. The research questions addressed in the study were as follows: (a) What was the prior experience with television classes?, (b) How did students accept the practice of not being able to ask questions anytime they wished?, (c) Did students feel that attendance should be taken in these large classes?, (d) Did the students like the testing method used for them?, and (e) Were there major technological problems?.

Results and Discussion

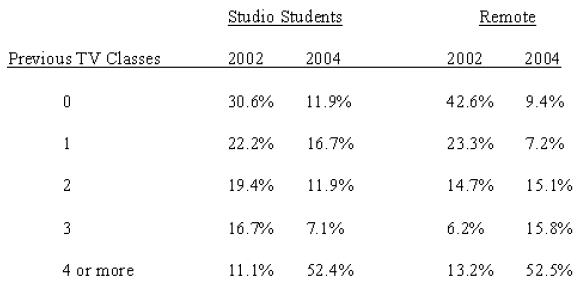

Distance learning has become more popular with students in general and with educational leadership students in particular. We wanted to see if this was true with our students, and we wanted to see to what

extent they had prior experience with television classes. Also, it is possible that the attitude of the on-campus students towards the off-campus arrangements (taking time for attendance, discussing technological problems, etc.) could be affected if they had also utilized these off-campus classes in the past. We also wanted to know the experience that the educational leadership students had previously had with television classes to see how popular this format was for educational leadership students.

While the majority of students in both 2002 groups had prior experience with television classes, less than 14% of either group had four or more courses. In 2004, over 52% of both groups had taken four or more courses by television before taking the courses that were surveyed. This is a large increase in the participation of students in distance education, and looking at the individual counts for the two universities (not shown here), this increase is evident for both places and from both groups of students studio and off-campus students. The figures show that over half of these students are taking, at the minimum, their fifth television course. Thus, whatever problems the students may have encountered, they continue to take courses with this delivery format. It should be noted that the studio students have taken the same number of courses via television (except this course).This may help explain why the majority of on-campus students were generally understanding of interruptions from off-campus sites, as shown in later results.

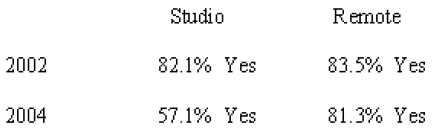

Technology enabled students at the remote sites to push a button to “dial in” to talk to the professor during class. When someone “dialed in,” a beep would sound in the studio classroom indicating that someone was calling. In discussing live television classes with other instructors, we were told that one common problem was that the students would call in without warning (unlike students raising their hands in class) and interrupt the flow of the class for all the other students and the instructor. In 2002, both of us told students that they could only call in to ask questions during designated question and answer times. Since this “waiting for permission to ask questions” was so different from the usual graduate classroom routine, we wondered how the students would accept this new procedure. In our 2002 classes, the students cooperated and did not call into the studio until we asked for questions or until we called on students to call in to answer questions. In the earlier survey, we asked the students for their opinion on this “no call-in” rule. The results of that i nquiry are summarized in the table below.

The 2002 results indicated that 82.1% of the studio students said that this rule was reasonable due to the class size, and 83.5% of the remote site students agreed. In 2004, the same rule was in place for the Ball State students (but was not used in South Carolina). The Ball State students at the remote sites responded in a manner similar to the students two years ago, with 81.3% saying that the rule was a good one because of the class size. However, in the studio, only 57.1% said that they agreed with this rule in 2004, possibly due to the small number in the studio (n=7), as one or two students were not happy that they could not get immediate responses from the instructor like they could in a traditional class. (They had been told that they would be treated like the remote-site students, having to wait for a designated time to ask questions.)

Since phone calls that came from the remote sites would make a buzzing noise, the studio students were asked if they were bothered by these call-ins. Findings indicated that, in 2002, 66.7% of the campus students said that it never bothered them, and 30.6% said that it sometimes bothered them. In 2004, 85.7% of the campus students stated that they were never bothered by the call-ins, with 14.3% saying that it sometimes bothered them. One assumption may be that with students taking more and more television courses, they have become used to the call-ins.

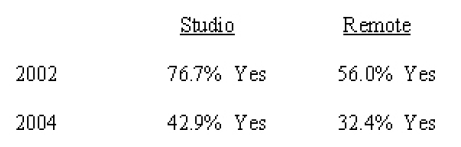

The size of the classes meant that attendance took longer. The students were asked whether it was still appropriate to take attendance in these large classes. The results of that inquiry are summarized in the table below.

In the studio class, in 2002, 76.7% said that attendance should be taken, while 56.0% of the remote-site students felt that taking attendance was appropriate. In 2004, the percentages declined: 42.9% of the studio students said that attendance should be taken, with 32.4% of the remote-site students agreeing.

Another change was the way in which the educational leadership students were tested. There were two options that did not require students to come to campus. We could use the usual pencil and paper examination and mail them to the remote sites where a proctor would supervise the exams and return them by mail, or we could put the exams on the Internet and students could take them by computer.

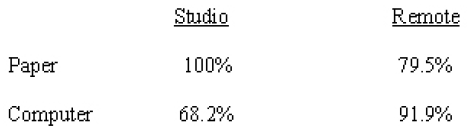

In 2002, both methods of testing were used. The students in the school finance class were given the written exams, and the students in the principalship class were tested by computer. When the students were asked whether they preferred the way they were examined or whether they would prefer the alternate method, students in both classes preferred the way they were tested, even though they were tested in different ways. The results of that inquiry are summarized in the table below.

For the studio class taking a paper test (finance class), 100% said that they would prefer a paper test; for the off-campus students taking a paper test, 79.5% said that they liked that method. For the studio classes that completed exams on computer (principalship class), 68.2% said that they would prefer the computer for taking exams; for the off-campus students taking the computer test, 91.9% said that they would prefer that method. This seems to suggest that either way is acceptable to students. Since access to computers was the same for all students and since paper tests could have been used for all students, it seems that students simply preferred what was given to them.

In 2004, all students were tested using written tests, and they were asked whether they would prefer taking their exams that way or whether they would prefer tests on a computer. For the studio students, 69.0% said that they would prefer the way they had been tested by written exams. For those at the remote sites, 66.9% said that they would have preferred to have been tested by computer rather than by written exams.

We also surveyed the students about technology problems. Students attending class in the studio were not required to use telephones or to ask questions, and they did not need to utilize the television technology to view or hear the professor. If any studio students had been adverse to technology, it would not have affected their class. For off-campus students, however, bad weather could cause major problems with both the telephones and television technology.

When asked about problems with the audio and/or video, 59.7% of the 2004 off-site students said that the system worked all the time, 38.1% said that it sometimes did not work but was not a problem, and 1.4% said that it did not work a lot of the time and was a problem for them. While these figures were a slight improvement over 2002, it should be remembered that one of the sites changed from Ball State to South Carolina. Still, it was reassuring to know that nearly 98% felt that they did not have a real problem with the television technology.

Students at the remote sites could call in for attendance or questions/answers on a phone system by pushing a button on a special phone at their site. This phone system worked all the time for 66.9% of the students in 2004, did not work sometimes but was not a problem for 27.3%, and did not work a lot of the time and was a problem for 2.9% of the students. As noted earlier, students were given a regular phone number to call into the television studio director's office and report problems with their special phones or problems with the television system. The director then notified us during the class and noted whether this was an isolated case or whether there were other sites that were having problems. Although 46.8% of the students did call into the studio to report technical problems, previously mentioned findings indicate that their outages were not considered a problem for most of them.

Off-campus students were asked if they ever had to order tapes/videostreaming of the presentations be-cause of technical problems. The responses (2004) indicated that 10.1% ordered one tape or videostreaming, 2.9% ordered more than one tape/videostreaming, and 86.3% did not have to order any recordings of the classes. Again, it appears that technical problems, though present at times, were not a major problem for the vast majority of the students, and there were provisions made for those who did have problems.

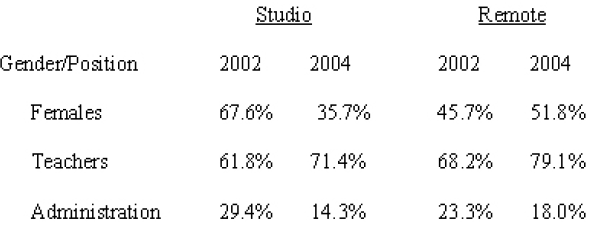

Previous researchers have sometimes stated that females had more problems with technology than males, and we wanted to see if females tended to take the on-campus class or the off-campus class or whether there was any difference in their choices. We also wanted to know what percentage of the students were classroom teachers and how many students taking these administrative courses were already school administrators. Finally, since recruitment of students is important to a department's survival, we wanted to know if we had students in our classes who were actually in programs at other universities and took our courses for convenience. Questions were asked to gather student information about gender and position. The results of that inquiry are summarized in the table below.

In 2004, the studio class was 35.7% female, while the off-campus students were 51.8% female. In the studio class in 2004, 71.4% of the students were classroom teachers, and 14.3% were school administrators. At the remote sites in 2004, 79.1% were teachers, with 18.0% stating that they were administrators. In 2002 we noted that females did select the on-campus class more than the off-campus sites. This was reversed in 2004, so no conclusions can be made about selection of sites by gender.

The reasons the students chose a particular method of course delivery was also an area of inquiry. The studio students were asked if they would have preferred to have taken the course off campus instead of coming to the studio. Although in 2004, 11.9% said that this was sometimes true, 85.7% stated that it was never true (a change from 30.6% and 69.4% in 2002, but similar if added together). The students who completed the course off-campus did not have to pay student fees (recreation, library use, sports and musical tickets, etc.) and only paid tuition for the three-hour graduate course. Students on campus had to pay the full tuition and fees amount. When we asked the off-campus students the advantage of taking a course on television, 93.5% said that it was for convenience. An important question for the off-campus students was the following: “Considering the advantages and the disadvantages of a television course, would you take another one if it was something that you needed and it was at a convenient site?” Responses indicated that 97.8% would take another televised course. Clearly, the advantages outweighed the disadvantages for these students.

Conclusions

Distance education experience was more evident in the 2004 survey. The “no-call-in” rule was considered reasonable by the students, and most of the on-campus students were not bothered by the phones. Taking attendance took quite a bit of class time, and students at both sites wished that taking attendance could be reduced or eliminated. There were problems with the technology, but these problems were not major for most students. Students who had no prior degrees from these two universities took the television courses, pointing out potential recruitment benefits of this method of instruction. When asked the reason that off-campus students completed the course by television, the overwhelming reason was the convenience of driving to a nearby site instead of traveling to campus.

The results were positive for our off-campus students and technology-based leadership development. The off-campus students received the same instruction as campus students for a lower cost, with no major technological problems, and at a convenient location. The on-campus students seemed to accept the various technological requirements necessary for our off-campus students. For school district leaders considering technology-based leadership development, the results are encouraging.

References

Jones, D. R., & Pritchard, A. L. (1999). Realizing the virtual university. Educational Technology, 39(5), 56-59.

Kelly, M. (1990). Course creation issues in distance education. In Education at a distance: From issues to practice (pp. 77-99). Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Lamb, A. C., & Smith, W. L. (2000). Ten facts of life for distance learning courses. Tech Trends, 44(1), 12-15.

Sharp, W. L., & Cox, E. P. (2003). Distance learning: A comparison of classroom students with off-campus television students. The Journal of Technology Studies, 29(1), 29-34.

Sinn, J. W. (2004). Electronic course delivery in higher education: Promise and challenge. The Journal of Technology Studies, 30(1), 24-28.

Souder, W. E. (1993). The effectiveness of traditional vs. satellite delivery in three management of technology master's degree programs. The American Journal of Distance Education, 7(1), 37-53.

Stammen, R., & Schmidt, M. (2001). Basic understanding for developing distance education for online instruction. NASSP Bulletin, 85(628), 47-50.

Swan, M. K., & Jackman, D. H. (2000). Comparing the success of students enrolled in distance education courses vs. face-to-face classrooms. The Journal of Technology Studies, 26(1), 58-63.

Weigel, T. (2000). E-Learning: The tradeoff between richness and research in higher education. Change, 33(5), 10-15.

- 3399 reads