Re-read Helvering v. Horst in chapter 2. Why did taxpayer Horst lose?

Helvering v. Eubank, 311 U.S. 122 (1940).

MR. JUSTICE STONE delivered the opinion of the Court.

This is a companion case to Helvering v. Horst, ... and presents issues not distinguishable from those in that case.

Respondent, a general life insurance agent, after the termination of his agency contracts and services as agent, made assignments in 1924 and 1928, respectively, of renewal commissions to become payable to him for services which had been rendered in writing policies of insurance under two of his agency contracts. The Commissioner assessed the renewal commissions paid by the companies to the assignees in 1933 as income taxable to the assignor in that year ... The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the order of the Board of Tax Appeals sustaining the assessment. We granted certiorari.

No purpose of the assignments appears other than to confer on the assignees the power to collect the commissions, which they did in the taxable year. ...

For the reasons stated at length in the opinion in the Horst case, we hold that the commissions were taxable as income of the assignor in the year when paid. The judgment below is

Reversed.

The separate opinion of MR. JUSTICE McREYNOLDS.

...

“The question presented is whether renewal commissions payable to a general agent of a life insurance company after the termination of his agency and by him assigned prior to the taxable year must be included in his income despite the assignment.”

“During part of the year 1924, the petitioner was employed by The Canada Life Assurance Company as its branch manager for the state of Michigan. His compensation consisted of a salary plus certain commissions. His employment terminated on September 1, 1924. Under the terms of his contract, he was entitled to renewal commissions on premiums thereafter collected by the company on policies written prior to the termination of his agency, without the obligation to perform any further services. In November, 1924, he assigned his right, title and interest in the contract, as well as the renewal commissions, to a corporate trustee. From September 1, 1924 to June 30, 1927, the petitioner and another, constituting the firm of Hart & Eubank, were general agents in New York City for the Aetna Life Assurance Company, and from July 1, 1927, to August 31, 1927, the petitioner individually was general agent for said Aetna Company. The Aetna contracts likewise contained terms entitling the agent to commissions on renewal premiums paid after termination of the agency, without the performance of any further services. On March 28, 1928, the petitioner assigned to the corporate trustee all commissions to become due him under the Aetna contracts. During the year 1933, the trustee collected by virtue of the assignments renewal commissions payable under the three agency contracts above mentioned amounting to some $15,600. These commissions were taxed to the petitioner by the commissioner, and the Board has sustained the deficiency resulting therefrom.”

The court below declared –

“In the case at bar, the petitioner owned a right to receive money for past services; no further services were required. Such a right is assignable. At the time of assignment, there was nothing contingent in the petitioner’s right, although the amount collectible in future years was still uncertain and contingent. But this may be equally true where the assignment transfers a right to income from investments, as in Blair v. Commissioner, 300 U.S. 5, and Horst v. Commissioner, 107 F.2d 906, or a right to patent royalties, as in Nelson v. Ferguson, 56 F.2d 121, cert. denied, 286 U.S. 565. By an assignment of future earnings, a taxpayer may not escape taxation upon his compensation in the year when he earns it. But when a taxpayer who makes his income tax return on a cash basis assigns a right to money payable in the future for work already performed, we believe that he transfers a property right, and the money, when received by the assignee, is not income taxable to the assignor.

Accordingly, the Board of Tax Appeals was reversed, and this, I think, is in accord with the statute and our opinions.

The assignment in question denuded the assignor of all right to commissions thereafter to accrue under the contract with the insurance company. He could do nothing further in respect of them; they were entirely beyond his control. In no proper sense were they something either earned or received by him during the taxable year. The right to collect became the absolute property of the assignee, without relation to future action by the assignor.

A mere right to collect future payments for services already performed is not presently taxable as “income derived” from such services. It is property which may be assigned. Whatever the assignor receives as consideration may be his income, but the statute does not undertake to impose liability upon him because of payments to another under a contract which he had transferred in good faith under circumstances like those here disclosed.

....

THE CHIEF JUSTICE and MR. JUSTICE ROBERTS concur in this opinion.

Notes and Questions:

- The Court’s majority says that this case presents issues like those in Horst, supra?

- Is that accurate?

- Should the right to collect compensation income for services performed become property simply by the passage of time, e.g., one year?

- Should the tax burden fall upon the one who earns the income only if that person receives the compensation in the same year?

- Do you see any latent problems of horizontal equity in the opinion of Justice McReynolds? Taxpayers have endeavored from the beginning to convert compensation income from ordinary income

into property. Courts are very careful not permit this to occur. Does not Justice McReynolds undermine the principles of Lucas v. Earl?

- Maybe the principles of Lucas v. Earl need undermining.

- Why do you think that taxpayer wanted to transfer his rights to receive future renewal commission to a corporation that he controlled? Were there tax advantages to doing this?

Blair v. Commissioner, 300 U.S. 5 (1937)

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE HUGHES delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case presents the question of the liability of a beneficiary of a testamentary trust for a tax upon the income which he had assigned to his children prior to the tax years and which the trustees had paid to them accordingly.

The trust was created by the will of William Blair, a resident of Illinois who died in 1899, and was of property located in that State. One-half of the net income was to be paid to the donor’s widow during her life. His son, the petitioner Edward Tyler Blair, was to receive the other one-half and, after the death of the widow, the whole of the net income during his life. In 1923, after the widow’s death, petitioner assigned to his daughter, Lucy Blair Linn, an interest amounting to $6,000 for the remainder of that calendar year, and to $9,000 in each calendar year thereafter, in the net income which the petitioner was then or might thereafter be entitled to receive during his life. At about the same time, he made like assignments of interests, amounting to $9,000 in each calendar year, in the net income of the trust to his daughter Edith Blair and to his son, Edward Seymour Blair, respectively. In later years, by similar instruments, he assigned to these children additional interests, and to his son William McCormick Blair other specified interests, in the net income. The trustees accepted the assignments and distributed the income directly to the assignees.

....

... The trustees brought suit in the superior court of Cook county, Illinois, to obtain a construction of the will ... [and the Illinois courts] found the assignments to be “voluntary assignments of a part of the interest of said Edward Tyler Blair in said trust estate” and, as such, adjudged them to be valid.

At that time, there were pending before the Board of Tax Appeals proceedings involving the income of the trust for the years 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1929. The Board ... [applied] the decision of [the Illinois courts and] overruled the Commissioner’s determination as to the petitioner’s liability. The Circuit Court of Appeals ... reversed the Board. That court recognized the binding effect of the decision of the state court as to the validity of the assignments, but decided that the income was still taxable to the petitioner upon the ground that his interest was not attached to the corpus of the estate, and that the income was not subject to his disposition until he received it.

Because of an asserted conflict with the decision of the state court, and also with decisions of circuit courts of appeals, we granted certiorari. ...

First. [Res judicata does not bar this case.]

Second. The question of the validity of the assignments is a question of local law. The donor was a resident of Illinois, and his disposition of the property in that State was subject to its law. By that law, the character of the trust, the nature and extent of the interest of the beneficiary, and the power of the beneficiary to assign that interest in whole or in part are to be determined. The decision of the state court upon these questions is final. Spindle v. Shreve, 111 U.S. 542, 547-548; Uterhart v. United States, 240 U.S. 598, 603; Poe v. Seaborn, 282 U.S. 101, 110; Freuler v. Helvering, supra, 291 U.S. 45. ... In this instance, it is not necessary to go beyond the obvious point that the decision was in a suit between the trustees and the beneficiary and his assignees, and the decree which was entered in pursuance of the decision determined as between these parties the validity of the particular assignments. ...

....

Third. The question remains whether, treating the assignments as valid, the assignor was still taxable upon the income under the federal income tax act. That is a federal question.

Our decisions in Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111, and Burnet v. Leininger, 285 U.S. 136, are cited. In the Lucas case, the question was whether an attorney was taxable for the whole of his salary and fees earned by him in the tax years, or only upon one-half by reason of an agreement with his wife by which his earnings were to be received and owned by them jointly. We were of the opinion that the case turned upon the construction of the taxing act. We said that “the statute could tax salaries to those who earned them, and provide that the tax could not be escaped by anticipatory arrangements and contracts, however skilfully devised, to prevent the salary when paid from vesting even for a second in the man who earned it.” That was deemed to be the meaning of the statute as to compensation for personal service, and the one who earned the income was held to be subject to the tax. In Burnet v. Leininger, supra, a husband, a member of a firm, assigned future partnership income to his wife. We found that the revenue act dealt explicitly with the liability of partners as such. The wife did not become a member of the firm; the act specifically taxed the distributive share of each partner in the net income of the firm, and the husband, by the fair import of the act, remained taxable upon his distributive share. These cases are not in point. The tax here is not upon earnings which are taxed to the one who earns them. Nor is it a case of income attributable to a taxpayer by reason of the application of the income to the discharge of his obligation. Old Colony Trust Co. v. Commissioner, 279 U.S. 716; [citations omitted]. There is here no question of evasion or of giving effect to statutory provisions designed to forestall evasion; or of the taxpayer’s retention of control. Corliss v. Bowers, 281 U.S. 376; Burnet v. Guggenheim, 288 U.S. 280.

In the instant case, the tax is upon income as to which, in the general application of the revenue acts, the tax liability attaches to ownership. SeePoe v. Seaborn, supra; [citation omitted].

The Government points to the provisions of the revenue acts imposing upon the beneficiary of a trust the liability for the tax upon the income distributable to the beneficiary. But the term is merely descriptive of the one entitled to the beneficial interest. These provisions cannot be taken to preclude valid assignments of the beneficial interest, or to affect the duty of the trustee to distribute income to the owner of the beneficial interest, whether he was such initially or becomes such by valid assignment. The one who is to receive the income as the owner of the beneficial interest is to pay the tax. If, under the law governing the trust, the beneficial interest is assignable, and if it has been assigned without reservation, the assignee thus becomes the beneficiary, and is entitled to rights and remedies accordingly. We find nothing in the revenue acts which denies him that status.

The decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals turned upon the effect to be ascribed to the assignments. The court held that the petitioner had no interest in the corpus of the estate, and could not dispose of the income until he received it. Hence, it was said that “the income was his,” and his assignment was merely a direction to pay over to others what was due to himself. The question was considered to involve “the date when the income became transferable.” The Government refers to the terms of the assignment – that it was of the interest in the income “which the said party of the first part now is, or may hereafter be, entitled to receive during his life from the trustees.” From this, it is urged that the assignments “dealt only with a right to receive the income,” and that “no attempt was made to assign any equitable right, title or interest in the trust itself.” This construction seems to us to be a strained one. We think it apparent that the conveyancer was not seeking to limit the assignment so as to make it anything less than a complete transfer of the specified interest of the petitioner as the life beneficiary of the trust, but that, with ample caution, he was using words to effect such a transfer. That the state court so construed the assignments appears from the final decree which described them as voluntary assignments of interests of the petitioner “in said trust estate,” and it was in that aspect that petitioner’s right to make the assignments was sustained.

The will creating the trust entitled the petitioner during his life to the net income of the property held in trust. He thus became the owner of an equitable interest in the corpus of the property. Brown v. Fletcher, 235 U.S. 589, 598-599; Irwin v. Gavit, 268 U.S. 161, 167-168; Senior v. Braden, 295 U.S. 422, 432; Merchants’ Loan & Trust Co. v. Patterson, 308 Ill. 519, 530, 139 N.E. 912. By virtue of that interest, he was entitled to enforce the trust, to have a breach of trust enjoined, and to obtain redress in case of breach. The interest was present property alienable like any other, in the absence of a valid restraint upon alienation. [citations omitted]. The beneficiary may thus transfer a part of his interest, as well as the whole. See Restatement of the Law of Trusts, §§ 130, 132 et seq. The assignment of the beneficial interest is not the assignment of a chose in action, but of the “right, title, and estate in and to property.” Brown v. Fletcher, supra; Senior v. Braden, supra. See Bogert, Trusts and Trustees, vol. 1, § 183, pp. 516, 517; 17 Columbia Law Review, 269, 273, 289, 290.

We conclude that the assignments were valid, that the assignees thereby became the owners of the specified beneficial interests in the income, and that, as to these interests, they, and not the petitioner, were taxable for the tax years in question. The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reversed, and the cause is remanded with direction to affirm the decision of the Board of Tax Appeals.

It is so ordered.

Notes and Questions:

1. On what basis did the court of appeals hold for the Commissioner? Compare that to the language of Horst.

2. The Court spent several paragraphs establishing that Edward Tyler Blair had the power to dispose of his interest as he wished. Why was the exercise of this discretion sufficient in this case to shift the tax burden to the recipient when it was not sufficient in Helvering v. Horst?

3. William Blair died. Through his will, he devised part of his property to a trust. We are not told who received the remainder of his property. Edward Tyler William Blair was an income beneficiary of part of the trust. We are not told of the final disposition of the corpus of the trust. We are told that Edward had no interest in the corpus of the estate. Edward assigned fractional interests “in each calendar year thereafter, in the net income which [Edward] was then or might thereafter be entitled to receive during his life.” It appears that Edward’s entire interest was as a beneficiary of the trust. He then assigned to various sons and daughters a fraction of his entire interest.

- Exactly what interest did William Blair, Jr. retain after these dispositions?

- Compare this to what the taxpayer in Helvering v. Horst, supra, chapter 3, retained.

- Is this difference a sound basis upon which the Court may reach different results?

4. Think of the ownership of “property” as the ownership of a “bundle of sticks.” Each stick represents some particular right. For example, a holder of a bond may own several sticks, e.g., the right to receive an interest payment in each of ten consecutive years might be ten sticks, the right to sell the bond might be another stick, the right to the proceeds upon maturity might be another stick. Imagine that we lay the sticks comprising a bond, one on top of the other. Then we slice off a piece of the property. We might slice horizontally – and thereby take all or a portion of only one or a few sticks. Or we might slice vertically – and thereby take an identically proportional piece of every stick.

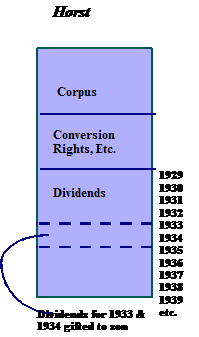

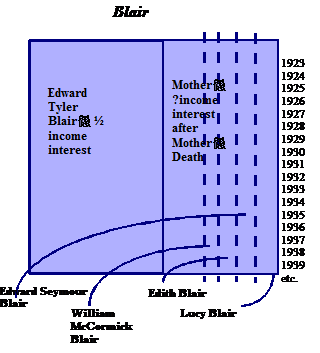

Consider the accompanying diagrams of Horst and Blair. Do they suggest an analytical model in “assignment of income derived from property” cases?

- Slice vertically rather than horizontally?

5. Taxpayer was the life beneficiary of a testamentary trust. In December 1929, she assigned a specified number of dollars from the income of the trust to certain of her children for 1930. The trustee paid the specified children as per Taxpayer’s instructions.

- Exactly what interest did Taxpayer retain after these dispositions?

- Should Taxpayer-life beneficiary or the children that she named to receive money in 1930 be subject to income tax on the trust income paid over to the children? SeeHarrison v. Schaffner, 312 U.S. 579, 582-83 (1941).

6. Taxpayer established a trust with himself as trustee and his wife as beneficiary. The trust was to last for five years unless either Taxpayer or his wife died earlier. Taxpayer placed securities that he owned in the trust. The trust’s net income was to be held for Taxpayer’s wife. Upon termination of the trust, the corpus was to revert to Taxpayer and any accumulated income was to be paid to his wife.

- Exactly what interest did Taxpayer retain after these dispositions?

- Should Taxpayer-settlor-trustee or his wife be subject to income tax on the trust income paid over to Taxpayer’s wife? SeeHelvering v. Clifford, 309 U.S. 331, 335 (1940).

6a. Now suppose that Taxpayer placed property in trust, the income from which was to be paid to his wife until she died and then to their children. Taxpayer “reserved power ‘to modify or alter in any manner, or revoke in whole or in part, this indenture and the trusts then existing, and the estates and interests in property hereby created[.]?’” Taxpayer did not in fact exercise this power, and the trustee paid income to Taxpayer’s wife.

- Exactly what interest did Taxpayer retain after this disposition?

- Should the trust income be taxable income to Taxpayer or to his wife?

- SeeCorliss v. Bowers, 281 U.S. 376, 378 (1930).

7. Again: is the tree-fruits analogy useful in difficult cases? Consider what happens when the fruit of labor is property from which income may be derived.

Heim v. Fitzpatrick, 262 F.2d 887 (2nd Cir. 1959).

Before SWAN and MOORE, Circuit Judges, and KAUFMAN, District Judge.

SWAN, Circuit Judge.

This litigation involves income taxes of Lewis R. Heim, for the years 1943 through 1946. On audit of the taxpayer’s returns, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue determined that his taxable income in each of said years should be increased by adding thereto patent royalty payments received by his wife, his son and his daughter. The resulting deficiencies were paid under protest to defendant Fitzpatrick, Collector of Internal Revenue for the District of Connecticut. Thereafter claims for refund were filed and rejected. The present action was timely commenced ... It was heard upon an agreed statement of facts and supplemental affidavits. Each party moved for summary judgment. The plaintiff’s motion was denied and the defendant’s granted. ...

Plaintiff was the inventor of a new type of rod end and spherical bearing. In September 1942 he applied for a patent thereon. On November 5, 1942 he applied for a further patent on improvements of his original invention. Thereafter on November 17, 1942 he executed a formal written assignment of his invention and of the patents which might be issued for it and for improvements thereof to The Heim Company. 1 This was duly recorded in the Patent Office and in January 1945 and May 1946 plaintiff’s patent applications were acted on favorably and patents thereon were issued to the Company. The assignment to the Company was made pursuant to an oral agreement, subsequently reduced to a writing dated July 29, 1943, by which it was agreed (1) that the Company need pay no royalties on bearings manufactured by it prior to July 1, 1943; (2) that after that date the Company would pay specified royalties on 12 types of bearings; (3) that on new types of bearings it would pay royalties to be agreed upon prior to their manufacture; (4) that if the royalties for any two consecutive months or for any one year should fall below stated amounts, plaintiff at his option might cancel the agreement and thereupon all rights granted by him under the agreement and under any and all assigned patents should revert to him, his heirs and assigns; and (5) that this agreement is not transferable by the Company.

In August 1943 plaintiff assigned to his wife ‘an undivided interest of 25 per cent in said agreement with The Heim Company dated July 29, 1943, and in all his inventions and patent rights, past and future, referred to therein and in all rights and benefits of the First Party (plaintiff) thereunder * * *.’ A similar assignment was given to his son and another to his daughter. Plaintiff paid gift taxes on the assignments. The Company was notified of them and thereafter it made all royalty payments accordingly. As additional types of bearings were put into production from time to time the royalties on them were fixed by agreement between the Company and the plaintiff and his three assignees.

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue decided that all of the royalties paid by the Company to plaintiff’s wife and children during the taxable years in suit were taxable to him. This resulted in a deficiency which the plaintiff paid ...

The appellant contends that the assignments to his wife and children transferred to them income-producing property and consequently the royalty payments were taxable to his donees, as held in Blair v. Commissioner, 300 U.S. 5. [footnote omitted]. Judge Anderson, however, was of opinion that (151 F. Supp. 576):

The income-producing property, i.e., the patents, had been assigned by the taxpayer to the corporation. What he had left was a right to a portion of the income which the patents produced. He had the power to dispose of and divert the stream of this income as he saw fit.

Consequently he ruled that the principles applied by the Supreme Court in Helvering v. Horst, 311 U.S. 112 and Helvering v. Eubank, 311 U.S. 122 required all the royalty payments to be treated as income of plaintiff.

The question is not free from doubt, but the court believes that the transfers in this case were gifts of income-producing property and that neither Horst nor Eubank requires the contrary view. In the Horst case the taxpayer detached interest coupons from negotiable bonds, which he retained, and made a gift of the coupons, shortly before their due date, to his son who collected them in the same year at maturity. Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111, which held that an assignment of unearned future income for personal services is taxable to the assignor, was extended to cover the assignment in Horst, the court saying,

Nor is it perceived that there is any adequate basis for distinguishing between the gift of interest coupons here and a gift of salary or commissions.

In the Eubank case the taxpayer assigned a contract which entitled him to receive previously earned insurance renewal commissions. In holding the income taxable to the assignor the court found that the issues were not distinguishable from those in Horst. No reference was made to the assignment of the underlying contract. 2

In the present case more than a bare right to receive future royalties was assigned by plaintiff to his donees. Under the terms of his contract with The Heim Company he retained the power to bargain for the fixing of royalties on new types of bearings, i.e., bearings other than the 12 products on which royalties were specified. This power was assigned and the assignees exercised it as to new products. Plaintiff also retained a reversionary interest in his invention and patents by reason of his option to cancel the agreement if certain conditions were not fulfilled. This interest was also assigned. The fact that the option was not exercised in 1945, when it could have been, is irrelevant so far as concerns the existence of the reversionary interest. We think that the rights retained by plaintiff and assigned to his wife and children were sufficiently substantial to justify the view that they were given income-producing property.

In addition to Judge Anderson’s ground of decision appellee advances a further argument in support of the judgment, namely, that the plaintiff retained sufficient control over the invention and the royalties to make it reasonable to treat him as owner of that income for tax purposes. Commissioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591 is relied upon. There a patent was licensed under a royalty contract with a corporation in which the taxpayer-inventor held 89% of the stock. An assignment of the royalty contract to the taxpayer’s wife was held ineffective to shift the tax, since the taxpayer retained control over the royalty payments to his wife by virtue of his control of the corporation, which could cancel the contract at any time. The argument is that, although plaintiff himself owned only 1% of The Heim Company stock, his wife and daughter together owned 68% and it is reasonable to infer from depositions introduced by the Commissioner that they would follow the plaintiff’s advice. Judge Anderson did not find it necessary to pass on this contention. But we are satisfied that the record would not support a finding that plaintiff controlled the corporation whose active heads were the son and son-in-law. No inference can reasonably be drawn that the daughter would be likely to follow her father’s advice rather than her husband’s or brother’s with respect to action by the corporation.

...

For the foregoing reasons we hold that the judgment should be reversed and the cause remanded with directions to grant plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment.

So ordered.

Contingent fee arrangements

What happens when a taxpayer-plaintiff enters a contingent fee arrangement with his/her attorney? Has taxpayer entered an “anticipatory arrangement” to which the assignment-of-income doctrine should apply? Or has taxpayer partially assigned income-producing property?

- Is the contingent-fee attorney a joint owner of the client’s claim?

- Does it matter that the relationship between client and attorney is principal and agent?

- No and yes, said the Supreme Court in CIR v. Banks, 543 U.S. 426 (2005). State laws that may protect the attorney do not change this, so long as it does not alter the fundamental principal-agent relationship.

- If taxpayer-plaintiff must include whatever damages s/he receives in his/her gross income, taxpayer-plaintiff must include the contingent fee that s/he pays his/her attorney.

Assume that plaintiff must include whatever damages s/he receives in his/her gross income. The expenses of producing taxable income are deductible. What difference does it make? See §§ 67 and 55(a), 56(b)(1)(A)(i) (alternative minimum tax). And see § 62(a)(20). When would § 62(a)(20) affect your answer?

If plaintiff’s recovery is not included in his/her gross income, why should s/he not even be permitted to deduct the expenses of litigation?

Notes and Questions:

1. Eubank involved labor that created an identifiable and assignable right to receive income in the future. How does Heim v. Fitzpatrick differ from Eubank? After all, a patent is the embodiment of (considerable) work.

2. A patent is also a capital asset, even to the “individual whose efforts created” it, that the holder has presumptively held for more than one year. § 1235(a), (b)(1). However, this rule does not apply to loss transfers between related persons under §§ 267(b) or 707(b).

- Does the existence of § 1235 lend inferential support to the court’s holding in Heim?

3. Do the CALI Lesson, Basic Federal Income Taxation: Assignment of Income: Property.

- Do not worry about questions 3 and 19.

- 3955 reads