In the world of finance, there are two common types of contracts between parties to buy or sell an asset at a specified future time. These are the forward contract and the futures contract. Both forward contracts and futures contracts are used to hedge investments. Although they have the same function, i.e. to buy or sell an asset at a specified future time, futures contracts and forward contracts also have distinct differences.

These are the forward contract and the futures contract. Both forward contracts and futures contracts are used to hedge investments. Although they have the same function, i.e. to buy or sell an asset at a specified future time, futures contracts and forward contracts also have distinct differences.

Forward contracts

A forward contract is a non-standardized contract between two parties. It is a private agreement to buy or sell a specific asset (such as wheat, oil, pigs, etc.) at a specific future date at a price agreed upon today. The two parties must bear each other's credit risk. A forward contract is not traded on an exchange, which means that it is not settled in cash daily.

Forward contracts are settled only at their maturity dates. The profit or loss made from a forward contract depends on the difference between the forward price and the spot price of the asset on the day the forward contract matures. When entering into a forward transaction, the buyer of the forward contract is said to hold the long position. The seller is said to hold the short position by agreeing to sell the asset on the same date for the same price.

The price that the underlying asset is bought/sold for is called the delivery price. This price is chosen so that the value of the contract to both sides is zero at the outset. What this means will be explained shortly — roughly, it means that the price is fair, so neither party is taking advantage of the other.

The payout from a forward is based on the fixed price of the underlying asset at the maturity date. An example of a forward contract is provided in the following animated presentation.

Let's assume that I enter into a forward transaction in which I agree to sell 100 pigs at a fixed price of $3,000 per pig in a year's time when the contract matures. Assume that I don't have any pigs at the moment. If the price of a pig is $3,500 at the maturity date, then I make a loss on the forward transaction because I must buy 100 pigs at a price of $3,500 each in order to meet my obligation to deliver the pigs. Note that the buyer and I can opt not to perform the contract, since this is a non-standardized agreement between us.

On delivery, I only receive $3,000 per pig, so I incur a total loss of $50,000, that is 100 × $(3,500 – 3,000). But let's say the price of pigs has plummeted to $2,500 each. In this case, I profit to the tune of $50,000, that is 100 × $(3,000 – 2,500).

Futures contracts

A futures contract is a bit different from a forward contract. A futures contract requires delivery of a commodity, bond, currency, or stock index, at a specified price, on a specified future date, and it involves a set of standardized rules that need to be specified. The profit and loss made by each party on a futures contract are equal and opposite. In other words, a futures contract trade is a zero-sum game.

There is, however, always a chance that a party may fail to perform on a futures contract as required by its side of the contract agreement. Thus a futures contract relies on margin calls to guarantee performance, without considering the benefit of the individual parties. An exchange or clearinghouse acts as a counterpart on all future contracts and sets margins.

A futures contract is an example of a parametric contract, and is easily combined or traded as part of more complex financial derivatives deals (such as stock and currency deals). The benefit of parties will not be considered. An example of a futures contract is provided in the following animated presentation. Click on the image below to launch it.

Unlike forward contracts, a futures contract involves a set of standardized rules that need to be specified. Such rules might include:

- the grade of the deliverable, for example, the quality of the pig (in size or weight);

- the delivery date, for example, one year from the agreement of the contract; and

- the amount and units of the underlying asset are to be traded.

For example, let's say that 100 pigs are to be traded at the price of $3,000 per pig. Again, assume that I don't have any pigs. If the price of a pig is $3,500 at the end of the year, I definitely make a loss on the future transaction because I must buy 100 pigs at $3,500 each in order to meet my obligation to deliver the pigs.

Pricing a forward

In order to explain the pricing problem, we are going to turn a forward transaction into a simple mathematical expression. To formulate the expression, we reconsider forward contracts in more detail.

Recall that a forward contract is an agreement to buy or sell an asset on a specified future date for a fixed price. Let

K be the fixed price (also called the strike price), and

ST be the spot price per pig at the maturity time T.

Supposing that the buyer has agreed to buy the pigs at the fixed price, then the payoff at time T from a long position is defined as

ST – K

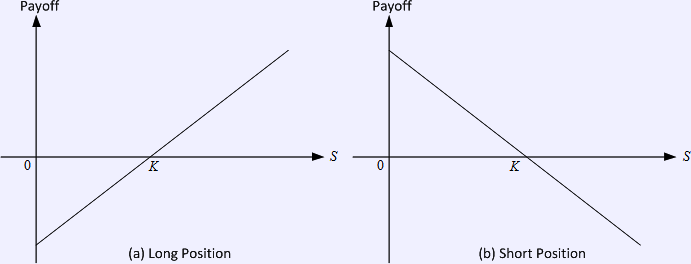

per pig, as illustrated in (a) in Figure 1.1. This payoff could be positive or negative, since the cost of entering into a forward contract is zero. The slope of (ST – K) is positive, meaning that the payoff rise is proportional to the increase in the spot price ST.

Similarly, the payoff at time T from a short position is defined as

K – ST

per pig (or per unit of an asset) if I have agreed to sell pigs at a fixed price. The payoff has a downward slope, as shown in (b) in Figure 1.1.

Our next problem is how we can determine a fair delivery price, i.e. the fixed price in the forward contract. At the time a contract is prepared, neither buyer nor seller knows the forward price at the maturity date, so we can use a simple strategy to estimate a fair price . The following animated presentation shows you how this can work.

Determining a fair delivery price for a forward contract

Let's assume that cash can be deposited at 5% interest per annum. If the fixed price is $3,000 per pig at the maturity date, and the forward price of a pig is $3,300, then we can borrow $3,000 at a 5% interest rate per year, so the annual interest repayment is $150; buy a pig on the market; enter into a short forward contract to sell a pig for $3,300 in one year's time; and, at the end of the year, sell the pig for $3,300, and repay the borrowed $3,000 plus $150 interest.

We have now made a risk-free profit of $150. In fact, any fixed price above $3,150 will result in a profit using this strategy.

But what if the fixed price is below $3,150? In this case, we can sell a pig for $3,000, assuming we have one; deposit $3,000 at a 5% interest rate per year; enter into a long forward contract to repurchase the pig in one year's time for the delivery price; and, at the end of the year, buy back the pig at the delivery price.

As long as the fixed price is under $3,150, a risk-free profit again emerges.

In theory, investors in the pig market will try to take advantage of any forward price that is not equal to $3,150. These trading activities are known as arbitrage, and will result in the forward price being exactly $3,150. This is known as an arbitrage free price because any other price results in an arbitrage opportunity.

What does all this tell us?

- First, the forward transaction costs nothing for either party to enter into. The arguments above show that either party could safely agree to the transaction without making a loss, through suitable borrowing/lending, etc.

- Second, the total return between the two parties will be the interest that can be earned on cash (such as the $150 in the example above). However, the payoff for one party is the opposite of that of the other, i.e. for every winner there is a loser. This illustrates the speculative nature of some of these instruments when they are traded in isolation. When future contracts are traded on their own for speculative purposes, e.g. on the Hang Seng Index, they can indeed be equivalent to betting on a racehorse.

(In fact, speculative trading in 'options' is actually far more dangerous than the kind of forward transaction we've considered here.)

Although this illustrates the potentially speculative nature of future transaction and the dangers of being able to enter into a large number of contracts at zero cost, there are a variety of ways in which these contracts can be used to reduce risk. This is known as hedging.

An example of hedging

Extending our pig case study, suppose a pig farmer has a good year in which his pigs breed 100 piglets. The current price is $3,000, and the farmer is concerned that this price may fall — or at least not grow in line with the one-year forward price of $3,150. He would be happy to receive $315,000 for selling the 100 pigs in a year's time. The farmer could therefore sell his 100 pigs in a forward contract. Alternatively, he could sell his 100 pigs when the piglets have grown up for a fixed amount of $315,000 in a year's time. This allows him to prevent a reduction in value due to the price of pigs falling, as well as enabling him to fix his future cash-flow in order to reduce the uncertainty of his business. The farmer has 'hedged' his exposure to pig prices — he has hedged his bets.

- 6851 reads