General Electric (GE) offers a dizzying array of products and services, including lightbulbs, jet engines, and loans. One way that GE could produce its lightbulbs would be to have individual employees work on one lightbulb at a time from start to finish. This would be very inefficient, however, so GE and most other organizations avoid this approach. Instead, organizations rely ondivision of labor when creating their products ("The Building Blocks of Organizational Structure" [Image missing in original]). Division of labor is a process of splitting up a task (such as the creation of lightbulbs) into a series of smaller tasks, each of which is performed by a specialist.

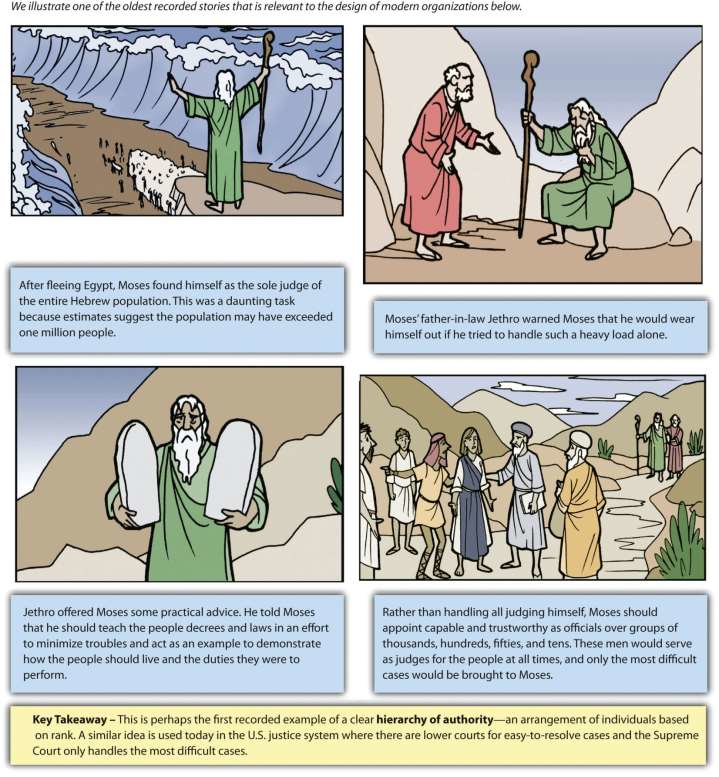

The leaders at the top of organizations have long known that division of labor can improve efficiency. Thousands of years ago, for example, Moses’s creation of a hierarchy of authority by delegating responsibility to other judges offered perhaps the earliest known example (Figure 9.3 Hierarchy of Authority ). In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith’s book The Wealth of Nations quantified the tremendous advantages that division of labor offered for a pin factory. If a worker performed all the various steps involved in making pins himself, he could make about twenty pins per day. By breaking the process into multiple steps, however, ten workers could make forty-eight thousand pins a day. In other words, the pin factory was a staggering 240 times more productive than it would have been without relying on division of labor. In the early twentieth century, Smith’s ideas strongly influenced Henry Ford and other industrial pioneers who sought to create efficient organizations.

While division of labor fuels efficiency, it also creates a challenge—figuring out how to coordinate different tasks and the people who perform them. The solution is organizational structure, which is defined as how tasks are assigned and grouped together with formal reporting relationships. Creating a structure that effectively coordinates a firm’s activities increases the firm’s likelihood of success. Meanwhile, a structure that does not match well with a firm’s needs undermines the firm’s chances of prosperity.

- 2821 reads