Organizational performance refers to how well an organization is doing to reach its vision, mission, and goals. Assessing organizational performance is a vital aspect of strategic management. Executives must know how well their organizations are performing to figure out what strategic changes, if any, to make. Performance is a very complex concept, however, and a lot of attention needs to be paid to how it is assessed.

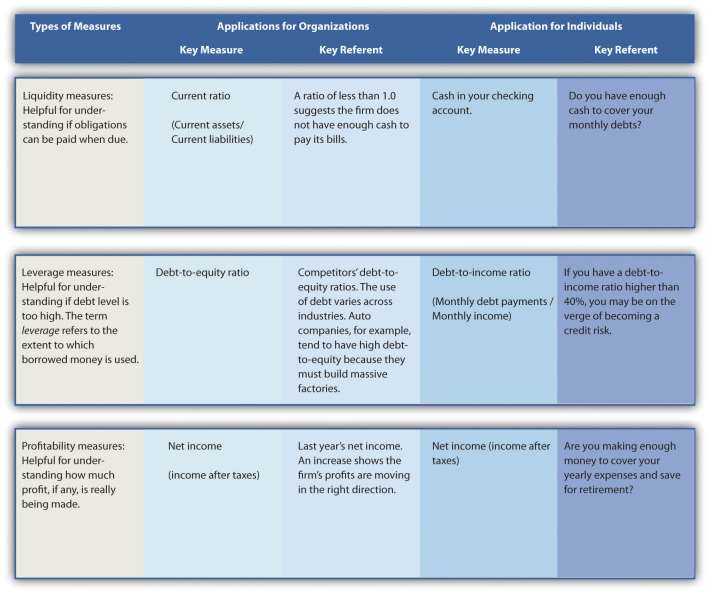

Two important considerations are (1) performance measures and (2) performance referents (Figure 2.4 How Organizations and Individuals Can Use Financial Performance Measures and Referents ). A performance measure is a metric along which organizations can be gauged. Most executives examine measures such as profits, stock price, and sales in an attempt to better understand how well their organizations are competing in the market. But these measures provide just a glimpse of organizational performance. Performance referents are also needed to assess whether an organization is doing well. A performance referent is a benchmark used to make sense of an organization’s standing along a performance measure. Suppose, for example, that a firm has a profit margin of 20 percent in 2011. This sounds great on the surface. But suppose that the firm’s profit margin in 2010 was 35 percent and that the average profit margin across all firms in the industry for 2011 was 40 percent. Viewed relative to these two referents, the firm’s 2011 performance is cause for concern.

Using a variety of performance measures and referents is valuable because different measures and referents provide different information about an organization’s functioning. The parable of the blind men and the elephant—popularized in Western cultures through a poem by John Godfrey Saxe in the nineteenth century—is useful for understanding the complexity associated with measuring organizational performance. As the story goes, six blind men set out to “see” what an elephant was like. The first man touched the elephant’s side and believed the beast to be like a great wall. The second felt the tusks and thought elephants must be like spears. Feeling the trunk, the third man thought it was a type of snake. Feeling a limb, the fourth man thought it was like a tree trunk. The fifth, examining an ear, thought it was like a fan. The sixth, touching the tail, thought it was like a rope. If the men failed to communicate their different impressions they would have all been partially right but wrong about what ultimately mattered.

This story parallels the challenge involved in understanding the multidimensional nature of organization performance because different measures and referents may tell a different story about the organization’s performance. For example, the Fortune 500 lists the largest US firms in terms of sales. These firms are generally not the strongest performers in terms of growth in stock price, however, in part because they are so big that making major improvements is difficult. During the late 1990s, a number of Internet-centered businesses enjoyed exceptional growth in sales and stock price but reported losses rather than profits. Many investors in these firms who simply fixated on a single performance measure—sales growth— absorbed heavy losses when the stock market’s attention turned to profits and the stock prices of these firms plummeted.

The number of performance measures and referents that are relevant for understanding an organization’s performance can be overwhelming, however. For example, a study of what performance metrics were used within restaurant organizations’ annual reports found that 788 different combinations of measures and referents were used within this one industry in a single year. 1 Thus executives need to choose a rich yet limited set of performance measures and referents to focus on.

- 瀏覽次數:3278