Although the government technically does not have an interest in punishing individuals for who they are, such as an impoverished person or a transient, the public perception of law enforcement is often affected by the presence of so-called vagrants and panhandlers in any given area. Thus virtually every jurisdiction has statutes punishing either vagrancy or loitering. However, these statutes are subject to constitutional attack if they are void for vagueness, overbroad, or target status.

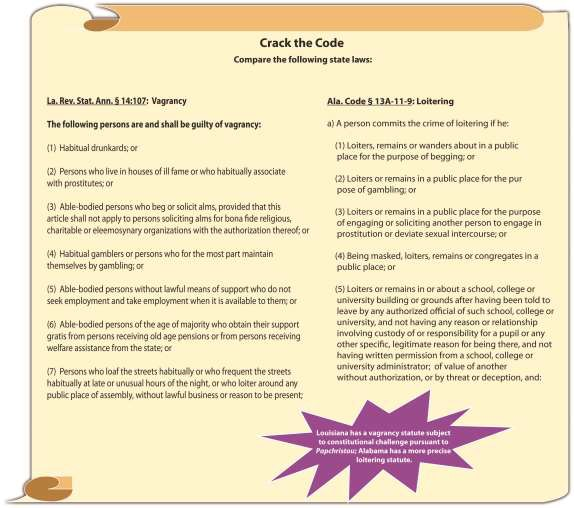

Historically, vagrancy statutes were broadly drafted to allow law enforcement considerable discretion in arresting the unemployed, gamblers, drug addicts, alcoholics, and those who frequented houses of prostitution or other locations of ill repute. In a sense, vagrancy statutes attempted to incapacitate individuals before they engaged in criminal activity, to ensure the safety and security of any given area.

In 1972, the US Supreme Court struck down a Florida vagrancy statute in Papachristouv. City of Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156 (1972). The Court held that the statute, which prohibited night walking, living off one’s spouse, and frequenting bars or liquor stores was void for vagueness and violated the due process clause in the Fourteenth Amendment. Thereafter, many states repealed or modified vagrancy statutes in lieu of more precisely drafted statutes prohibiting specific criminal conduct such as loitering. The Model Penal Code prohibits public drunkenness and drug incapacitation (Model Penal Code § 250.5) and loitering or prowling (Model Penal Code § 250.6). To summarize US Supreme Court precedent refining loitering statutes: it is unconstitutional to target those who are unemployed 1 or to enact a statute that is vague, such as a statute that criminalizes loitering in an area “with no apparent purpose,” 2 or without the ability to provide law enforcement with “credible and reliable identification.” 3

In a jurisdiction that criminalizes loitering, the criminal act element is typically loitering, wandering, or remaining, with the specific intent or purposely to gamble, beg, or engage in prostitution. ] 4 An attendant circumstance could specify the location where the conduct takes place, such as a school or transportation facility. 5 Another common attendant circumstance is being masked in a public place while loitering, with an exception for defendants going to a masquerade party or participating in a public parade. 6 The Model Penal Code prohibits loitering or prowling in a place, at a time, or in a manner not usual for law-abiding individuals under circumstances that warrant alarm for the safety of persons or property in the vicinity (Model Penal Code § 250.6). Loitering is generally graded as a misdemeanor 7 or a violation. 8 The Model Penal Code grades loitering as a violation (Model Penal Code § 250.6).

Many jurisdictions also criminalize panhandling or begging. Panhandling statutes essentially criminalize speech, so they must be narrowly tailored to avoid successful constitutional challenges based on the First Amendment, void for vagueness, or overbreadth. Constitutional panhandling statutes generally proscribe aggressive conduct 9 or conduct that blocks public access or the normal flow of traffic.

- 3931 reads