For customers, the Web facilitates search. Search engines such as Excite, Yahoo!, and Lycos allow the surfer to seek products and services by brand from a multitude of Web sites all over the world. They are also able to hunt for information on solutions to problems from a profusion of sites, and access the opinions and experiences of their peers in different parts of the world by logging on to bulletin boards and chat rooms. The use of such agents has been touted to reduce buyers' search costs across standard on-line storefronts, specialized on-line retailers, and online megastores, and to transform a diverse set of offerings into an economically efficient market. The new promise of intelligent agents (pieces of software that will search, shop, and compare prices and features on a surfer's behalf) gives the Internet shopper further buying power and choice.

The search phase in the consumer decision-making process, which can be costly and time-consuming in the real world, is reduced in terms of both time and expense in the virtual. An abundance of choice leads to customer sophistication. Customers become smarter, and exercise this choice by shopping around, making price comparisons, and seeking greatest value in a more assertive way. Marketers attempt to deal with this by innovation, but this in turn leads to imitation by competitors. Imitation leads to more oversupply in markets, which further accelerates the cycle of competitive rationality by creating more consumer choice. The Web has the potential to accelerate this cycle of competition at a rate that is unprecedented in history, creating huge pricing freedoms for customers, and substantial pricing dilemmas for marketers.

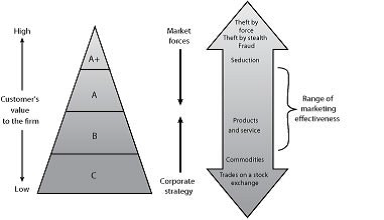

There are two simple but powerful models that may enable us to gain greater insight into pricing strategies on the Web. We integrate these into a scheme that is illustrated graphically in See Figure 8.1. The first of these simply applies the well-known Pareto-principle, also known as the 80-20 rule, to the customer base of any firm. For most organizations, all customers are not created equal --some are much more valuable than others. For example, one Mexican cellular phone company found that less than 10 percent of its customers accounted for around 90 percent of its sales, and that about 80 percent of customers accounted for less than 10 percent. Seen another way, while margins earned on the most valuable customers allowed the Mexican company to recoup its investment in them in a matter of months, low-value customers took more than six years to repay the firm's investment in them.

In the diagram in See Figure 8.1, we have divided a firm's customer base into four groups, which may best be understood in terms of the frequent flyer schemes run by most airlines nowadays. By far the largest group numerically, the C category customers nevertheless account for a very small percentage of an airline's revenues and profits. These are probably customers who are not even members of the frequent flyer program, and if they are, they are likely to be blue card members who inevitably never accumulate enough air miles to be able to spend on anything. They are unlikely to be loyal customers; they don't fly often, and when they do, their main consideration is the ticket price. For the sake of a few dollars, euros, or yen, they will happily switch airlines and fly on less than convenient schedules. Category B customers are like the silver card frequent flyers of an airline. They fly more frequently than Cs, and may even accumulate enough miles or points to claim rewards. However, they are still likely to be price sensitive, and exhibit signs of promiscuity by shopping around for the cheapest fares. The A category customers represent great value to the firm--in airline terms these are gold card holders. They use the product or service very frequently, and are probably so loyal to the firm that they do not shop around for price, even when there may be significant differences between suppliers. Because they represent substantial value to a firm such as an airline, they may be rewarded not only with miles, but special treatment, such as upgrades, preferential seating, and the use of lounges. Finally, the A+ category of customers represents a very small, but very valuable, group who account for a disproportionately large contribution to revenues and profits. Not only do these customers reap the rewards of value and loyalty, they are probably known by name to the firm, which inevitably performs service beyond the normal for them. An unsubstantiated but persistent rumor has it that there is a small handful of British Airways customers for whom the airline will even delay the Concord!

The second model in Figure 8.1 is derived from Deighton and Grayson's (1995) notion of a spectrum of exchange based on the extent to which an exchange between actors is voluntary. Thus, at one extreme, exchange between actors can be seen as extremely involuntary, as in the case of theft by force. At least one party to this type of exchange does not wish to participate, but is forced to by the other's actions. At the other extreme, an example of an extremely voluntary form of exchange would be the trading of stocks or shares by two traders on a stock exchange trading floor. This type of exchange is unambiguously fair , with no need for inducement for either party to act. Here, both actors participate entirely voluntarily for mutual gain--neither is able to buy or sell better shares or stocks at a price. Indeed, economists would argue that this bilateral exchange is the closest approximation to pure competition in the microeconomic sense. The two fully informed parties believe that each will be better off after the exchange. The market is highly efficient if price itself contains all the information that the parties need to make their decisions. Market efficiency is the percentage of maximum total surplus extracted in a market. In competitive price theory, the predicted market efficiency is 100 percent where the trading maximizes all possible gains of buyers and sellers from the exchange.

Returning once more to the other end of the spectrum, the next least voluntary form of exchange between actors is theft by stealth, where one actor appropriates the possessions of the other without the other's knowledge. This follows on to the next point of fraud, where one party to the exchange enters into a transaction with the other in such a way that he or she is deliberately deceived, tricked, or cheated into giving up possessions without receiving the expected payment in return. Back on the other extreme of the spectrum, there are commodity exchanges, where actors buy and sell commodities such as gold, oil, copper, grain, and pork bellies. There is little or no difference between the product of one supplier and another--gold is gold is gold, commodities are commodities. The price of the commodity contains sufficient information for the parties to decide whether they will transact, and one seller's commodity is exactly the same as another's.

Between the extremes of the spectrum there is a gray area, which we label a range of marketing effectiveness. Adjacent to fraud there is what Deighton and Grayson refer to as seduction, which is an interaction between marketer and consumer that transforms the consumer's initial resistance to a course of action into willing, even avid, compliance. Seduction induces consumers to enjoy things they did not intend to enjoy, because the marketer entices the consumer to abandon one set of social agreements and collaborate in the forging of another.

Second, and next to commodities, there is the vast array of products and services purchased and consumed by customers. While the customer may in many cases be seduced into purchasing these, frequently some of these products and services bear many of the characteristics of commodities. In a differentiated market, products vary in terms of quality or cater to different consumer preferences, but frequently the only real differences between them may be a brand name, packaging, formulation, or the service attached to them.

Where does marketing, as we know it, work best along this spectrum of exchange? The answer is, in a narrow band, labeled the range of marketing effectiveness; straddling most products and services, and extending from somewhere near the middle of seduction, to somewhere near the near edge of commodities. Here, the parties are not equally informed. There is information asymmetry, and the merit of the transaction being more or less certain for one than the other. Marketing induces customers to exchange by selling, informing or making promises to them. Obviously, activities such as theft by force or stealth, and also fraud, cannot be seen as marketing. Yet, marketing is also unnecessary, or at best perfunctory, at the other end of the spectrum. Two traders on a stock exchange floor can hardly be said to market to each other when they trade bundles of stocks or shares. The price contains all the information the parties to the transaction need to do the deal. The market is simply too efficient in these areas for marketing to work well--almost paradoxically, it is true to say that marketing is not effective when markets are efficient.

Bringing the two concepts (the Pareto distribution of the customer base, and the exchange spectrum) together may help us understand pricing strategy more effectively, particularly with regard to the effect of the Web on pricing for both sellers and customers. The objective of firms, with regard to the Pareto distribution, should be to:

- migrate as many customers upward as possible. That is, to turn C customers into Bs, Bs into As, and so forth. By doing this, the firm will increase its customer equity, or in simple terms, maximize the value of its customer transaction base.

- Forces in the market, however, including competition and the customer sophistication, tend to:

- force the customer distribution down, turning As to Bs, and Bs to Cs.

- Similarly, in the case of the exchange spectrum, marketing's task is one of:

- moving products or services away from the zone of commodities, and more to the location of seduction.

- Likewise the marketplace forces of competition and customer sophistication have the effect of:

- commoditization, a process by which the complex and the difficult become simple and easy--so simple and easy that anybody can do them, and does. Commoditization is a natural outcome of competition and technological advance, people learn better ways to make things and how to do so cheaper and faster. Prices plunge and essential differences vanish. Cheap PCs and mass-market consumer electronics are obvious examples of this.

It is thus incumbent upon managers to understand the forces that may impel markets towards a preponderance of C customers, and products and services towards commodities. Technology is manifesting itself in many such effects, and the Web is an incubator at present. On a more positive note, technology also offers managers some exciting tools with which to overcome the effects of market efficiency and with which to halt, or at least decelerate, the inevitable degradation of the customer base. These are the issues that are now addressed.

- 瀏覽次數:2755