While most academics and practitioners might be starting to think about, and even acknowledge, the importance of a Web site as a marketing communication tool, to date little systematic research has been conducted into the nature and effectiveness of this medium. Most of the work done so far has been of a descriptive nature--"what the medium is," using such surrogate measures as the size of the Web audience to indicate its potential. While these endeavors might add to our general understanding, they do not address more specific issues of concern, such as the communication objectives that advertisers might have, and how they expect Web sites to achieve these objectives. Neither do these studies assess the effectiveness of this new medium from the perspective of the recipient of the message (the buyer , to use the broadest marketing term).

The Web is rather like a cross between an electronic trade show and a community flea market. As an electronic trade show , it can be thought of as a giant international exhibition hall where potential buyers can enter at will and visit prospective sellers. Like a trade show, they may do this passively, by simply wandering around, enjoying the sights and sounds, pausing to pick up a pamphlet or brochure here, and a sticker, key ring, or sample there. Alternatively, they may become vigorously interactive in their search for information and want-satisfaction, by talking to fellow attendees, actively seeking the booths of particular exhibitors, carefully examining products, soliciting richer information, and even engaging in sales transactions with the exhibitor. The basic ingredients are still the same. As a flea market , it possesses the fundamental characteristics of openness, informality, and interactivity, a combination of a community and a marketplace or marketspace. A flea market is an alternative forum that offers the consumer an additional search option, which may provide society with a model for constructing more satisfying and adaptive marketplace options. The Web has much in common with a flea market.

The central and fundamental problem facing conventional trade show and flea marketers is how to convert visitors, casually strolling around the exhibition center or market, into customers at best, or leads at least. Similarly, a central dilemma confronting the Web advertiser is how to turn surfers (those who browse the Web) into interactors (attracting the surfers to the extent that they become interested; ultimately purchasers; and, staying interactive, repeat purchasers). An excellent illustration of a Web site as electronic trade show or flea market is to be found at the site established by Security First Network Bank, which was one of the first financial services institutions to offer full-service banking on the Internet. The company uses the graphic metaphor of a conventional bank to communicate and interact with potential and existing customers, including an electronic inquiries desk, electronic brochures for general information, and electronic tellers to deal with routine transactions. Thus, the degree of interaction is dependent on the individual surfer--those merely interested can take an electronic stroll through the bank, while those desiring more information can find it. Customers can interact to whatever degree they wish--transfer funds, make payments, write electronic checks, talk with electronic tellers (where they are always first in line), and see the electronic bank manager for additional requests, complaints, and general feedback.

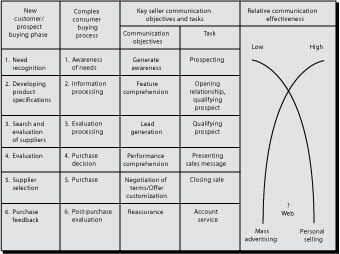

We have taken the notion of trade shows as a marketing communication tool and extended it to the possible role of the Web site as an advertising medium. This is speculated upon, in the context of both the buying and selling process stages, and in both industrial and consumer contexts, in See Figure 5.1. The relative (to mass advertising and personal selling) communication effectiveness of a Web site is questioned graphically in Figure 5.1, although without prior quantitative data, it is mere conjecture at this stage to posit a profile. By simply placing a question mark between mass advertising and personal selling in the figure, we tempt the reader to contemplate the communication profile of the Web. Industrial buying can be thought of as the series of stages in the first column in See Buying and selling and Web marketing communication. The buyer's information needs differ at each stage, as do the tasks of the marketing communicator. In column 2, a model of the steps in the consumer decision making process for complex purchases is shown, and it will be seen that these overlap the steps in the buying phases model to a considerable extent. The tasks that confront the advertiser and the seller in both industrial and consumer markets can similarly be mapped against these stages, through a series of communication objectives . This is shown in column 3. Each of these objectives requires different communication tasks of the seller, and these are similarly outlined in column 4. So, for example, generating awareness of a new product might be most effectively achieved through broadcast advertising, while closing a sale would best be achieved face to face, in a selling transaction. Most marketers, in both consumer and business-to-business markets, employ a mix of communication tools to achieve various objectives in the marketing communication process, judiciously combining advertising and personal selling.

The relative cost-effectiveness of advertising and personal selling in performing marketing communication tasks depends on the stage of the buying process, with personal selling becoming more cost effective the closer the buyer gets to the latter phases in the purchasing sequence--this is shown in column 5. A central question then is where does a Web site fit in terms of communication effectiveness? Again, rather than profile this, we leave it to the reader.

At this point, we re-emphasize the fact that the Web is still in its infancy, which means that no identifiable attempts have so far appeared in scholarly journals that methodically clarify its anticipated role and performance. This deficiency probably stems from the fact that few organizations or individuals have even begun to spell out their objectives in operating a Web site, let alone quantified them. This is not entirely unexpected--unlike expenditure on broadcast advertising, or the long-term financial commitment to a sales force, the establishment of a Web site is a relatively inexpensive venture, from which retraction is easy and rapid. It is not unlikely that many advertisers are on the Web simply because it is relatively quick and easy, and because they fear that the consequences of not having a presence will outweigh whatever might be the outcomes of a hastily ill-conceived presence. This lack of clear and quantified objectives, understanding, and the absence of a unified framework for evaluating performance, have compelled decision makers to rely on intuition, imitation, and advertising experience when conceptualizing, developing, designing, and implementing Web sites.

These two concerns--the lack of clear or consistent objectives and the relationship of those objectives to the variables under the control of the firm--are the issues that engage us here. We propose a more direct assessment of Web site performance using multiple indices such that differing Web site objectives can be directly translated into appropriate performance measures. We then explicitly link these performance measures to tactical variables under the control of the firm and present a conceptual framework to relate several of the most frequently mentioned objectives of Web site participation to measures of performance associated with Web site traffic flow. Finally, we develop a set of models linking the tactical variables to six performance measures that Web advertisers and marketers can use to measure the effectiveness and performance against objectives of a Web site. Finally, we discuss normative implications and suggest areas for further development.

- 瀏覽次數:3544