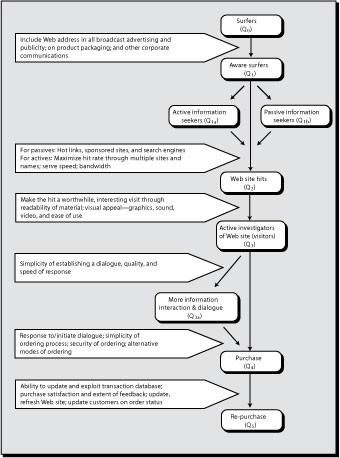

Based on the above, we model the flow of surfer activity on a Web site as a six-stage process, which is shown in Figure 5.2. The variables and measures shown in Figure 5.2 are defined in Table 5.1.

|

Variable |

Meaning |

|

Q 0 |

Number of people with Web access |

|

Q 1 |

Number of people aware of the site |

|

Q 2 |

Number of hits on the site |

|

Q 3 |

Number of active visitors to the site |

|

Q 4 |

Number of purchases |

|

Q 5 |

Number of repurchases |

All surfers on the Web may not be the relevant target audience for a given firm. Surfers can be in one of two groups:

- those potentially interested in the organization (η 0),

- those not interested (1-η 0).

The attractiveness of having a Web site for the organization depends on Q0η0, the number of potentially interested surfers on the Web (where Q0 is the net size measured in terms of surfers). The first stage of the model represents the flow of surfers on the net to land on the firm's Web site, and it is acknowledged that only a fraction of the aware surfers (Q0η0) visits a firm's Web site. This describes the awareness efficiency (η0) of the Web site. The awareness efficiency measures how effectively the organization is able to make surfers aware of its Web site. Advertisers and marketers can employ reasonably common and well-known awareness-generating techniques to affect this, such as including the Web site address in all advertising and publicity, on product packaging and other corporate communication materials, such as letterheads, business cards, and brochures.

The awareness efficiency index is:

The second stage of the model concerns attempts to get aware surfers to find the Web site. We distinguish between active and passive information seekers. Active seekers (Q1a) are those who intentionally seek to hit the Web site, whereas passive seekers (Q1b) are those aware surfers whose primary purpose in surfing was not necessarily to hit the Web site. Only a fraction of the aware surfers visit the firm's Web site. The second stage of the model thus represents the locatability/attractability efficiency (η1) of the Web site. This measures how effectively the organization is able to convert aware surfers into Web site hits, either by facilitating active seeking behavior (surfers who actively look for the Web site), or by attracting passive seekers (not actively looking for the Web site, but not against finding it).

Enabling active seekers to hit the Web site easily can be achieved by maximizing the locatability of the site--such as using multiple sites (e.g., Web servers in the U.S., Europe, and Asia), names for the site that can be easily guessed (e.g., www.apple.com), and enhancing server speed and bandwidth (the number of visits which can be handled concurrently). Tools to attract passive seekers include using a large number of relevant hot links (e.g., EDS has a link from ISWorld, the Web site for information systems academics, to its Web site), embedding hot links in sponsored Web sites (e.g., IBM sponsors the Wimbledon Tennis Tournament Web site), and banner ads on search engines. We summarize the locatability/attractability index as:

where hits refers to the number of surfers who alight on the Web site.

At this stage, it should be apparent that there is a difference between a hit and a visit . Merely hitting or landing on a site does not mean that the surfer did anything with the information to be found there--the surfer might simply hit and move on. A visit, as compared to a hit, implies greater interaction between the surfer and the Web page. It may mean spending appreciable time (i.e., > x minutes) reading the page. Alternatively, it could be completing a form or querying a database. Although the operational definition of a visit is to some extent dependent on the content and detail on the page, the overriding distinctive feature of a visit is some interaction between the surfer and the Web page.

The next phase of the model concerns the efficiency and ability of the Web site in converting the hit to a visit. The third stage of our model represents the contact efficiency ( η 2 ) of the Web site. This measures how effectively the organization transforms Web site hits into visits. The efforts of the advertiser at this stage should be focused on turning a hit into a worthwhile visit. Thus, the hit should be interesting, hold the visitor's attention, and persuade them to stay awhile to browse. The material should be readable--the concept of readability is a well-established principle in advertising communication. Visual effects should be appealing--sound and video can hold interest as well as inform. The possibility of gaining something, such as winning a prize in a competition, may be effective. The interface should be easy and intuitive. We summarize the contact efficiency index as:

Once the visitor is engaged--in real time--in a visit at the Web site, he or she should be able to do one or both of the following:

- establish a dialogue (at the simplest level, this may be signing an electronic visitors' book; at higher levels, this may entail e-mail requests for information). The visitors' book at the Robert Mondavi Wineries' Web site not only allows visitors to complete a questionnaire and thus receive very attractive promotional material, including a recipe brochure, it also allows the more inquisitive visitor to ask specific questions by e-mail. It is important to note that it is feasible to establish the dialogue in a way that elicits quite detailed information from the visitor--for example, by offering the visitor the opportunity to participate in a competition in exchange for information in the form of an electronic survey, or by promising a reward for interaction (the recipe booklet in the preceding example).

- place an order. This may be facilitated by ensuring simplicity of the ordering process, providing a secure means of payment, as well as options on mode of payment (e.g., credit card, check, electronic transfer of funds). Alternative ordering methods might also be provided (e.g., telephone, e-mail, or a postal order form that can be downloaded and printed). For example, the electronic music store CDnow offers a huge variety of CDs and other items such as tapes and video cassettes. It provides visitors with thousands of reviews from the well-respected All-Music Guide as well as thousands of artists' biographies. A powerful program built into the site allows a search for recordings by artist, title, and key words. It also tells about an artist's musical influences and lists other performers in the same genre. Each name is hotlinked so that a mouse click connects the visitor to even more information. CDnow's seemingly endless layers of sub-directories makes it easy and fun to get lost in a world of information, education, and entertainment--precisely the ingredients for inducing flow through the model. More importantly, from a measurability perspective, the site converts some of its many visitors to buyers.

This capability to turn visitors into purchasers, we term conversion efficiency, and summarize it in the form of an index as follows:

The final stage in the process entails converting purchases into re-purchases. The firm should consider the proficiency of the Web site not only to create purchases, but to turn these buyers into loyal customers who revisit the site and purchase on an ongoing basis. Variables which the marketer can influence include:

- regular updating and refreshing of the Web site. It is more likely that customers will revisit a Web site that is regularly revised and kept current;

- soliciting purchase satisfaction and feedback to improve the product specifically, and interaction generally;

- regular updating and exploiting of the transaction database. Once captured, customer data becomes a strategic asset, which can be used to further refine and retarget electronic marketing efforts. This can take a number of forms: customers can be reminded electronically to repurchase (e.g., an e-mail to a customer to have a car serviced); customers can be invited to collaborate with the marketer (e.g., loyal customers can be rewarded for referrals by supplying the e-mail addresses of friends or colleagues who may be leads).

This capability to turn purchasers into repurchasers, we term retention efficiency, and summarize as follows:

Finally, we define a sixth, or overall average Web site efficiency index ( ηAv ), which can be thought of as a summary of the process outlined in See Buying and selling and Web marketing communication .

This index can be an effective way to establish the extent to which Web site advertising and marketing objectives have been met. The measure is particularly relevant for a Web direct mail order

operation where the main objective is to generate purchases and repeat purchases. However, a simple average may in other cases be misleading, and a more refined and appropriate measure might be

a weighted average. A weighted average index is defined below:

where µi is the weighting accorded to each of the five efficiency indices in the model. So, for example, some advertisers might regard visits to the Web site as a very important criterion of its success (objective), without wishing or expecting these visits to necessarily result directly in sales. Other advertisers and marketers might want the visit to result in dialogue, which could result in sales, but only indirectly--mailing or faxing further information, accepting a free product sample, or requesting a sales call. Another group of Web advertisers might wish to emphasize retention efficiency. They would want to use the Web as a medium for establishing dialogue with existing customers and facilitating routine reordering. It would therefore be useful for advertisers and marketers wishing to establish overall Web efficiency to be able to weight Web objectives in terms of their relative importance.

- 瀏覽次數:2905