Geographic segments. Geography probably represents the oldest basis for segmentation. Regional differences in consumer tastes for products as a whole are well-known. Markets according to location are easily identified and large amounts of data are usually available. Many companies simply do not have the resources to expand beyond local or regional levels; thus, they must focus on one geographic segment only. Domestic and foreign segments are the broadest type of geographical segment.

Closely associated with geographic location are inherent characteristics of that location: weather, topography, and physical factors such as rivers, mountains, or ocean proximity. Conditions of high humidity, excessive rain or draught, snow or cold all influence the purchase of a wide spectrum of products. While marketers no longer segment markets as being east or west of the Mississippi River in the US, people living near the Mississippi river may constitute a viable segment for several products, such as flood insurance, fishing equipment, and dredging machinery.

Population density can also place people in unique market segments. High-density states in the US such as California and New York and cities such as New York City, Hong Kong, and London create the need for products such as security systems. fast-food restaurant and public transportation.

Geographic segmentation offers some important advantages. There is very little waste in the marketing effort, in that the product and supporting activities such as advertising, physical distribution, and repair can all be directed at the customer. Further, geography provides a convenient organizational framework. Products, salespeople, and distribution networks can all be organized around a central, specific location.

The drawbacks in using a geographic basis of segmentation are also notable. There is always the obvious possibility that consumer preferences may (unexpectedly) bear no relationship to location. Other factors, such as ethnic origin or income, may overshadow location. The stereotypical Texan from the USA, for example, is hard to find in Houston, where one-third of the population has immigrated from other states. Another problem is that most geographic areas are very large, regional locations. It is evident that the Eastern seaboard market in the US contains many subsegments. Members of a geographic segment often tend to be too heterogeneous to qualify as a meaningful target for marketing action.

Demographic segments. Several demographic characteristics have proven to be particularly relevant when marketing to ultimate consumers. Segmenting the consumer market by age groups has been quite useful for several products. For example, the youth market (approximately 5 to 13) not only influences how their parents spend money, but also when they make purchases of their own. Manufacturers of products such as toys, records, snack foods, and video games have designed promotional efforts directed at this group. More recently, the elderly market (age 65 and over) has grown in importance for producers of products such as low-cost housing, cruises, hobbies, and health care.

Gender has also historically been a good basis for market segmentation. While there are some obvious products designed for men or women, many of these traditional boundaries are changing, and marketing must apprise themselves of these changes. The emergence of the working women, for instance, has made determination of who performs certain activities in the family (e.g. shopping, car servicing), and how the family income is spent more difficult. New magazines such as Food & Wine, Men's Vogue, Marriage Partnership, and Father's Quarterly indicate how media is attempting to subsegment the male segment. Thus, the simple classification of male versus female may be useful only if several other demographic and behavioral characteristics are considered as well.

Another demographic trait closely associated with age and sex is the family life cycle. There is evidence that, based on family structure (i.e. number of adults and children), families go through very predictable behavioral patterns. For example, a young couple who have one young child will have far different purchasing needs than a couple in their late fifties whose children have moved out. In a similar way, the types of products purchased by a newly married couple will differ from those of a couple with older children.7

Income is perhaps the most common demographic oasis for segmenting a market. This may be partly because income often dictates who can or cannot afford a particular product. It is quite reasonable, for example, to assume that individuals earning minimum wage could not easily purchase a USD 25,000 sports car. Income tends to be a better basis for segmenting markets as the price tag for a product increases. Income may not be quite as valuable for products such as bread, cigarettes, and motor oil. Income may also be helpful in examining certain types of buying behavior. For example, individuals in the lower-middle income group are prone to use coupons. Playboy recently announced the introduction of a special edition aimed at the subscribers with annual incomes over USD 45,000.

Several other demographic characteristics can influence various of consumer activities. Education, for example, affects product preferences as well as characteristics demanded for certain products. Occupation can also be important. Individuals who work in hard physical labor occupations (e.g. coal mining) may demand an entirely different set of products than a person employed as a teacher or bank teller, even though their incomes are the same. Geographic mobility is somewhat related to occupation, in that certain occupations (e.g. military, corporate executives) require a high level of mobility. High geographic mobility necessitates that a person (or family) acquire new shopping habits, seek new sources of products and services, and possibly develop new brand preferences. Finally, race and national origin have been associated with product preferences and media preferences. African Americans have exhibited preferences in respect to food, transportation, and entertainment, to name a few. Hispanics tend to prefer radio and television over newspapers and magazines as a means for learning about products. The following integrated marketing box discusses how race may be an overlooked segment.8,9

Integrated marketing

Seeking the African-American Web community

Silas Myers is a new millennium African-American. He is 31, holds an MBA from Harvard University, works as an investment analyst for money manager Hotchkeo & Wiley, and pulls in a salary

close to six figures. He spends about 10 hours a week online, buying everything from a JVC portable radio to Arm & Hammer deodorant. "Maybe I am nuts," he says, "but shopping online is so

much easier to me."

Millions of African-Americans are online. They are younger, more affluent, and better educated than their offline kin. And they're not tiptoeing onto the Internet. They are right at home.

Five million blacks now cruise through cyberspace, nearly equaling the combined number of Hispanic, Asian, and Native American surfers, according to researcher Cyber Dialogue.

True, Internet use among African-Americans continues to lag behind the online white population: 28 per cent of blacks as opposed to 37 per cent for whites. It is time to take a closer look at

the digital divide. While those who do not have Internet access tend to be poor and undereducated, there is a large group of African Americans who are spending aggressively on the Web. "We

are looking at a tidal wave coming of African-American-focused content and online consumers," says Omar J. Wasow, executive director of BlackPlanet.com, a black-oriented online community. "You ignore it at your peril."

With good reason, African-Americans have become smitten with the ability to compare prices and find bargains online. Melvin Crenshaw, manager of Kidpreneurs magazine, recently used the

Travelocity website to save USD 300 on a ski trip to Denver. "I really liked the value," he says.

It's a shame, then, that so few sites market to such an attractive group. Almost every bookstore on the street has a section in African-American or ethnic literature. So it is shocking that

e-commerce giants like Amazon.com do not have ethnic book sections. The solution is easy. Web merchants can create what the National Urban League's B. Keith Fulton calls "micro bundles", web

categories within a site's merchandise that resemble the inner-city black bookstore or clothier. "You want blacks to click on a button and feel like they are in virtual Africa or virtual

Harlem," says Fulton, the Urban League's director of Technology programs and policy. To attract blacks, he recommends decorating that corner of the site in kinte cloth patterns.

1

Even religion is used as a basis for segmentation. Several interesting findings have arisen from the limited research in this area. Aside from the obvious higher demands for Christian-oriented magazines, books, music, entertainment, jewelry, educational institutions, and counseling services, differences in demand for secular products and services have been identified as well. For example, the Christian consumer attends movies less frequently than consumers in general and spends more time in volunteer, even non-church-related, activities.

Notwithstanding its apparent advantage (i.e. low cost and ease of implementation), considerable uncertainty exists about demographic segmentation. The method is often misused. A typical misuse of the approach has been to construct "profiles" of product users. For example, it might be said that the typical consumer of Mexican food is under 35 years of age, has a college education, earns more than USD 10,000 a year, lives in a suburban fringe of a moderate-size urban community, and resides in the West. True, these characteristics do describe a typical consumer of Mexican food, but they also describe a lot of other consumers as well, and may paint an inaccurate portrait of many other consumers.

Usage segments. In 1964, Twedt made one of the earliest departures from demographic segmentation when he suggested that the heavy user, or frequent consumer, was an important basis for segmentation. He proposed that consumption should be measured directly, and that promotion should be aimed directly at the heavy user. This approach has become very popular, particularly in the beverage industry (e.g. beer, soft drinks, and spirits). Considerable research has been conducted with this particular group and the results suggest that finding other characteristics that correlate with usage rate often greatly enhances marketing efforts.10

Four other bases for market segmentation have evolved from the usage-level criteria. The first is purchase occasion. Determining the reason for an airline passenger's trip, for instance, may be the most relevant criteria for segmenting airline consumers. The same may be true for products such as long-distance calling or the purchase of snack foods. The second basis is user status. It seems apparent that communication strategies must differ if they are directed at different use patterns, such as nonusers versus ex-users, or one-time users versus regular users. New car producers have become very sensitive to the need to provide new car buyers with a great deal of supportive information after the sale in order to minimize unhappiness after the purchase. However, determining how long this information is necessary or effective is still anybody's guess. The third basis is loyalty. This approach places consumers into loyalty categories based on their purchase patterns of particular brands. A key category is the brand-loyal consumer. Companies have assumed that if they can identify individuals who are brand loyal to their brand, and then delineate other characteristics these people have in common, they will locate the ideal target market. There is still a great deal of uncertainty as to how to correctly measure brand loyalty. The final characteristic is stage of readiness. It is proposed that potential customers can be segmented as follows: unaware, aware, informed, interested, desirous, and intend to buy. Thus if a marketing manager is aware of where the specific segment of potential customers is, he/she can design the appropriate market strategy to move them through the various stages of readiness. Again, these stages of readiness are rather vague and difficult to accurately measure.

Psychological segments. Research results show that the concept of segmentation should recognize psychological as well as demographic influences. For example, Phillip Morris has segmented the market for cigarette brands by appealing psychologically to consumers in the following way:

- Marlboro: the broad appeal of the American cowboy

- Benson & Hedges: sophisticated, upscale appeal

- Parliament: a recessed filter for those who want to avoid direct contact with tobacco

- Merit: low tar and nicotine

- Virginia Slims: appeal based on "You've come a long way, baby" theme

Evidence suggests that attitudes of prospective buyers towards certain products influence their subsequent purchase or non-purchase of them. If persons with similar attitudes can be isolated, they represent an important psychological segment. Attitudes can be defined as predispositions to behave in certain ways in response to given stimulus.11

Personality is defined as the long-lasting characteristics and behaviors of a person that allow them to cope and respond to their environment. Very early on, marketers were examining personality traits as a means for segmenting consumers. None of these early studies suggest that measurable personality traits offer much prospect of market segmentation. However, an almost inescapable logic seems to dictate that consumption of particular products or brands must be meaningfully related to consumer personality. It is frequently noted that the elderly drive big cars, that the new rich spend disproportionately more on housing and other visible symbols of success, and that extroverts dress conspicuously.12

Motives are closely related to attitudes. A motive is a reason for behavior. A buying motive triggers purchasing activity. The latter is general, the former more specific. In theory this is what market segmentation is all about. Measurements of demographic, personality, and attitudinal variables are really convenient measurements of less conspicuous motivational factors. People with similar physical and psychological characteristics are presumed to be similarly motivated. Motives can be positive (convenience), or negative (fear of pain). The question logically arises: why not observe motivation directly and classify market segments accordingly?

Lifestyle refers to the orientation that an individual or a group has toward consumption, work, and play and can be defined as a pattern of attitudes, interests, and opinions held by a person. Lifestyle segmentation has become very popular with marketers, because of the availability of measurement devices and instruments, and the intuitive categories that result from this process.13 As a result, producers are targeting versions of their products and their promotions to various lifestyle segments. Thus, US companies like All State Insurance are designing special programs for the good driver, who has been extensively characterized through a lifestyle segmentation approach.14,15

Lifestyle analysis begins by asking questions about the consumer's activities, interests, and opinions. If a man earns USD 40,000-USD 50,000 per year as an executive, with a wife and four children, what does he think of his role as provider versus father? How does he spend his spare time? To what clubs and groups does he belong? Does he hunt? What are his toward advertising? What does he read?

AIO (activities, interests, opinions) inventories, as they are called, reveal vast amounts of information concerning attitudes toward product categories, brands within product categories, and user and non-user characteristics. Lifestyle studies tend to focus upon how people spend their money; their patterns of work and leisure; their major interests; and their opinions of social and political issues, institutions, and themselves. The popularity of lifestyles as a basis for market segmentation has prompted several research firms to specialize in this area. However, few have achieved the success of VALS and VALS 2 developed by SRI International.

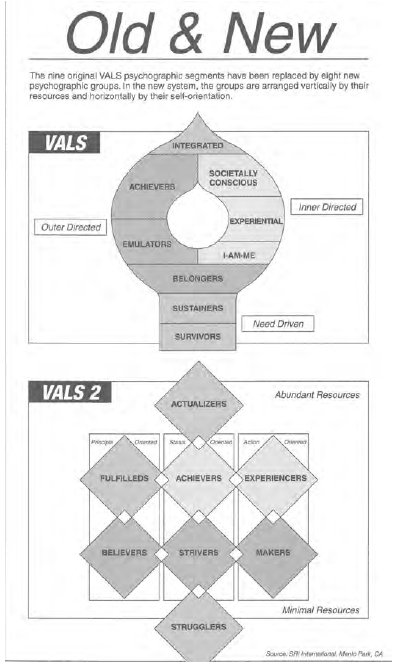

Introduced in 1978, the original VALS (Values, Attitudes, and Lifestyle) divided the American population into nine segments, organized along a hierarchy of needs. After several years of use, it was determined that the nine segments reflected a population dominated by people in their 20s and 30s, as the US was ten years ago. Moreover, businesses found it difficult to use the segments to predict buying behavior or target consumers. For these reasons, SRl developed an all-new system, VALS 2. It dropped values and lifestyles as its primary basis for its psychographic segmentation scheme. Instead, the 43 questions ask about unchanging psychological stances rather than shifting values and lifestyles.

The psychographic groups in VALS 2 are arranged in a rectangle (see Figure 2.5). They are stacked vertically by their resources (minimal to abundant) an horizontally by their self-orientation (principle, status, or action-oriented).

An annual subscription to VALS 2 provides businesses with a range of products and services. Businesses doing market research can include the VALS questions in their questionnaire. SRl will analyze the data and VALS-type the respondents.

- 4575 reads