Normally, all the measures of a piece of music must have exactly the number of beats indicated in the time signature. The beats may be filled with any combination of notes or rests (with duration values also dictated by the time signature), but they must combine to make exactly the right number of beats. If a measure or group of measures has more or fewer beats, the time signature must change.

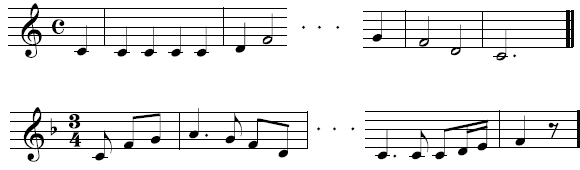

There is one common exception to this rule. (There are also some less common exceptions not discussed here.) Often, a piece of music does not begin on the strongest downbeat. Instead, the strong beat that people like to count as "one" (the beginning of a measure), happens on the second or third note, or even later. In this case, the first measure may be a full measure that begins with some rests. But often the first measure is simply not a full measure. This shortened first measure is called a pickup measure.

If there is a pickup measure, the final measure of the piece should be shortened by the length of the pickup measure (although this rule is sometimes ignored in less formal written music). For example, if the meter of the piece has four beats, and the pickup measure has one beat, then the final measure should have only three beats. (Of course, any combination of notes and rests can be used, as long as the total in the first and final measures equals one full measure.

- 3180 reads