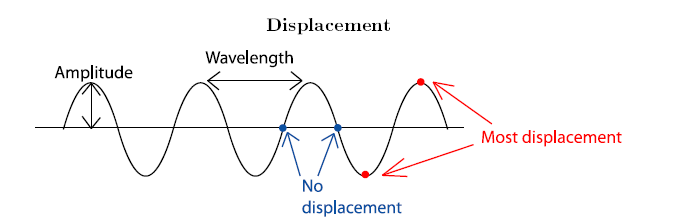

Both transverse and longitudinal waves cause a displacement of something: air molecules, for example, or the surface of the ocean. The amount of displacement at any particular spot changes as the wave passes. If there is no wave, or if the spot is in the same state it would be in if there was no wave, there is no displacement. Displacement is biggest (furthest from "normal") at the highest and lowest points of the wave. In a sound wave, then, there is no displacement wherever the air molecules are at a normal density. The most displacement occurs wherever the molecules are the most crowded or least crowded.

The amplitude of the wave is a measure of the displacement: how big is the change from no displacement to the peak of a wave? Are the waves on the lake two inches high or two feet? Are the air molecules bunched very tightly together, with very empty spaces between the waves, or are they barely more organized than they would be in their normal course of bouncing off of each other?

Scientists measure the amplitude of sound waves in decibels. Leaves rustling in the wind are about 10 decibels; a jet engine is about 120 decibels.

Musicians call the loudness of a note its dynamic level. Forte (pronounced "FOR-tay") is a loud dynamic level; piano is soft. Dynamic levels don't correspond to a measured decibel level. An orchestra playing "fortissimo" (which basically means "even louder than forte") is going to be quite a bit louder than a string quartet playing "fortissimo". (See Dynamics (Section 1.3.1) for more of the terms that musicians use to talk about loudness.) Dynamics are more of a performance issue than a music theory issue, so amplitude doesn't need much discussion here.

- 3184 reads