Transposing instruments are instruments for which standard parts are written higher or lower than they sound. A very accomplished player of one of these instruments may be able to transpose at sight, saving you the trouble of writing out a transposed part, but most players of these instruments will need a transposed part written out for them. Here is a short list of the most common transposing instruments. For a more complete list and more information, see Transposing Instruments.

Transposing Instruments

- Clarinet is usually (but not always) a B flat instrument. Transpose C parts up one whole step for B flat instruments. (In other words, write a B flat part one whole step higher than you want it to sound.)

- Trumpet and Cornet parts can be found in both B flat and C, but players with B flat instruments will probably want a B flat (transposed) part.

- French Horn parts are usually in F these days. However, because of the instrument's history, older orchestral parts may be in any conceivable transposition, even changing transpositions in the middle of the piece. Because of this, some horn players learn to transpose at sight. Transpose C parts up a perfect fifth to be read in F.

- Alto and Baritone Saxophone are E flat instruments. Transpose parts up a major sixth for alto sax, and up an octave plus a major sixth for bari sax.

- Soprano and Tenor Saxophone are B flat instruments. Tenor sax parts are written an octave plus one step higher.

Note: Why are there transposing instruments? Sometimes this makes things easier on instrumentalists; they may not have to learn different fingerings when they switch from one kind of saxophone to another, for example. Sometimes, as with piccolo, transposition centers the music in the staff (rather than above or below the staff). But often transposing instruments are a result of the history of the instrument. See the history of the French horn40 to find out more.

The transposition you will use for one of these instruments will depend on what type of part you have in hand, and what instrument you would like to play that part. As with any instrumental part, be aware of the range of the instrument that you are writing for. If transposing the part up a perfect fifth results in a part that is too high to be comfortable, consider transposing the part down a perfect fourth instead.

To Decide Transpositions for Transposing Instruments

- Ask: what type of part am I transposing and what type of part do I want? Do you have a C part and want to turn it into an F part? Do you want to turn a B flat part into a C part? Non-transposing parts are considered to be C parts. The written key signature has nothing to do with the type of part you have; only the part's transposition from concert pitch (C part) matters for this step.

- Find the interval between the two types of part. For example, the difference between a C and a B flat part is one whole step. The difference between an E flat part and a B flat part is a perfect fifth.

- Make sure you are transposing in the correct direction. If you have a C part and want it to become a B flat part, for example, you must transpose up one whole step. This may seem counterintuitive, but remember, you are basically compensating for the transposition that is "built into" the instrument. To compensate properly, always transpose by moving in the opposite direction from the change in the part names. To turn a B flat part into a C part (B flat to C = up one step), transpose the part down one whole step. To turn a B flat part into an E flat part (B flat to E flat = down a perfect fifth), transpose the part up a perfect fifth.

- Do the correct transposition by interval, including changing the written key by the correct interval.

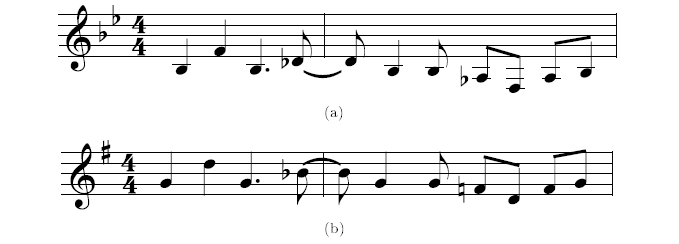

Example

Your garage band would like to feature a solo by a friend who plays the alto you’re your songwriter has written the solo as it sounds on his keyboard, so you have a C art. Alto sax is an E

flat instrument; in other words, when he sees a C, he plays an E flat, the note a major sixth (Major and Minor Intervals) lower. To compensate for this, you must write the part a major sixth

higher than your C part.

Example

Your choral group is performing a piece that includes an optional instrumental solo for clarinet. You have no clarinet player, but one group member plays recorder, a C instrument. Since the

part is written for a B flat instrument, it is written one whole step higher than it actually sounds. To write it for a C instrument, transpose it back down one whole step.

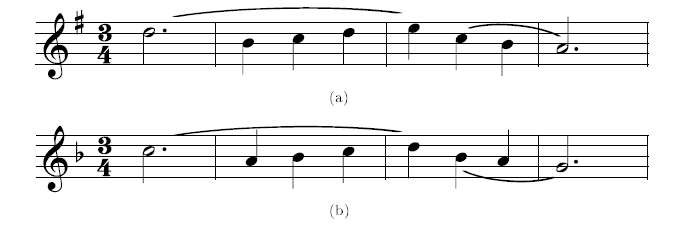

Exercise 6.4:

There's a march on your community orchestra's program, but the group doesn't have quite enough trombone players for a nice big march-type sound. You have extra French horn players, but they can't read bass clef C parts.

- 6303 reads