In the early days of the Internet, there were only a few number of hosts (mainly minicomputers) connected to the network. The most popular applications were remote login and file transfer. By 1983, there were already five hundred hosts attached to the Internet. Each of these hosts were identified by a unique IPv4 address. Forcing human users to remember the IPv4 addresses of the remote hosts that they want to use was not user-friendly. Human users prefer to remember names, and use them when needed. Using names as aliases for addresses is a common technique in Computer Science. It simplifies the development of applications and allows the developer to ignore the low level details. For example, by using a programming language instead of writing machine code, a developer can write software without knowing whether the variables that it uses are stored in memory or inside registers.

Because names are at a higher level than addresses, they allow (both in the example of programming above, and on the Internet) to treat addresses as mere technical identifiers, which can change at will. Only the names are stable. On today’s Internet, where switching to another ISP means changing your IP addresses, the user-friendliness of domain names is less important (they are not often typed by users) but their stability remains a very important, may be their most important property.

The first solution that allowed applications to use names was the hosts.txt file. This file is similar to the symbol table found in compiled code. It contains the mapping between the name of each Internet host and its associated IP address 1. It was maintained by SRI International that coordinated the Network Information Center (NIC). When a new host was connected to the network, the system administrator had to register its name and IP address at the NIC. The NIC updated the hosts.txt file on its server. All Internet hosts regularly retrieved the updated hosts.txt file from the server maintained by SRI. This file was stored at a well-known location on each Internet host (see RFC 952) and networked applications could use it to find the IP address corresponding to a name.

A hosts.txt file can be used when there are up to a few hundred hosts on the network. However, it is clearly not suitable for a network containing thousands or millions of hosts. A key issue in a large network is to define a suitable naming scheme. The ARPANet initially used a flat naming space, i.e. each host was assigned a unique name. To limit collisions between names, these names usually contained the name of the institution and a suffix to identify the host inside the institution (a kind of poor man’s hierarchical naming scheme). On the ARPANet few institutions had several hosts connected to the network.

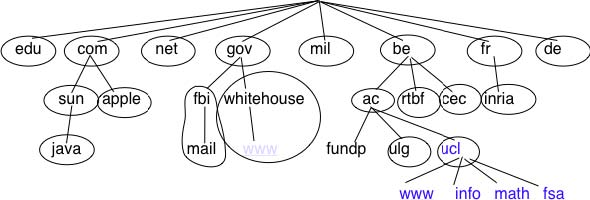

However, the limitations of a flat naming scheme became clear before the end of the ARPANet and RFC 819 proposed a hierarchical naming scheme. While RFC 819 discussed the possibility of organising the names as a directed graph, the Internet opted eventually for a tree structure capable of containing all names. In this tree, the top-level domains are those that are directly attached to the root. The first top-level domain was .arpa 2. This top-level name was initially added as a suffix to the names of the hosts attached to the ARPANet and listed in the hosts.txt file. In 1984, the .gov, .edu, .com, .mil and .org generic top-level domain names were added and RFC 1032 proposed the utilisation of the two letter ISO-3166 country codes as top-level domain names. Since ISO-3166 defines a two letter code for each country recognised by the United Nations, this allowed all countries to automatically have a top-level domain. These domains include .be for Belgium, .fr for France, .us for the USA, .ie for Ireland or .tv for Tuvalu, a group of small islands in the Pacific and .tm for Turkmenistan. Today, the set of top-level domain-names is managed by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Recently, ICANN added a dozen of generic top-level domains that are not related to a country and the .cat top-level domain has been registered for the Catalan language. There are ongoing discussions within ICANN to increase the number of top-level domains.

Each top-level domain is managed by an organisation that decides how sub-domain names can be registered. Most top-level domain names use a first-come first served system, and allow anyone to register domain names, but there are some exceptions. For example, .gov is reserved for the US government, .int is reserved for international organisations and names in the .ca are mainly reserved for companies or users who are present in Canada.

RFC 1035 recommended the following BNF for fully qualified domain names, to allow host names with a syntax which works with all applications (the domain names themselves have a much richer syntax).

This grammar specifies that a host name is an ordered list of labels separated by the dot (.) character. Each label can contain letters, numbers and the hyphen character (-) 3. Fully qualified domain names are read from left to right. The first label is a hostname or a domain name followed by the hierarchy of domains and ending with the root implicitly at the right. The top-level domain name must be one of the registered TLDs 4. For example, in the above figure, www.whitehouse.gov corresponds to a host named www inside the whitehouse domain that belongs to the gov top-level domain. info.ucl.ac.be corresponds to the info domain inside the ucl domain that is included in the ac sub-domain of the be top-level domain.

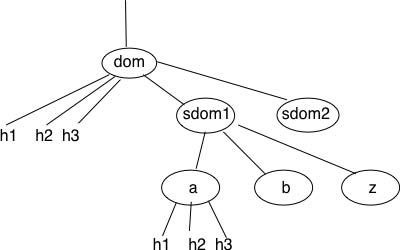

This hierarchical naming scheme is a key component of the Domain Name System (DNS). The DNS is a distributed database that contains mappings between fully qualified domain names and IP addresses. The DNS uses the client-server model. The clients are hosts that need to retrieve the mapping for a given name. Each nameserver stores part of the distributed database and answers the queries sent by clients. There is at least one nameserver that is responsible for each domain. In the figure below, domains are represented by circles and there are three hosts inside domain dom (h1, h2 and h3) and three hosts inside domain a.sdom1.dom. As shown in the figure below, a sub-domain may contain both host names and sub-domains.

A nameserver that is responsible for domain dom can directly answer the following queries :

- the IP address of any host residing directly inside domain dom (e.g. h2.dom in the figure above)

- the nameserver(s) that are responsible for any direct sub-domain of domain dom (i.e. sdom1.dom and sdom2.dom in the figure above, but not z.sdom1.dom)

To retrieve the mapping for host h2.dom, a client sends its query to the name server that is responsible for domain .dom. The name server directly answers the query. To retrieve a mapping for h3.a.sdom1.dom a DNS client first sends a query to the name server that is responsible for the .dom domain. This nameserver returns the nameserver that is responsible for the sdom1.dom domain. This nameserver can now be contacted to obtain the nameserver that is responsible for the a.sdom1.dom domain. This nameserver can be contacted to retrieve the mapping for the h3.a.sdom1.dom name. Thanks to this organisation of the nameservers, it is possible for a DNS client to obtain the mapping of any host inside the .dom domain or any of its subdomains. To ensure that any DNS client will be able to resolve any fully qualified domain name, there are special nameservers that are responsible for the root of the domain name hierarchy. These nameservers are called root nameserver. There are currently about a dozen root nameservers 5.

Each root nameserver maintains the list 6 of all the nameservers that are responsible for each of the top-level domain names and their IP addresses 7. All root nameservers are synchronised and provide the same answers. By querying any of the root nameservers, a DNS client can obtain the nameserver that is responsible for any top-level-domain name. From this nameserver, it is possible to resolve any domain name.

To be able to contact the root nameservers, each DNS client must know their IP addresses. This implies, that DNS clients must maintain an up-to-date list of the IP addresses of the root nameservers 8. Without this list, it is impossible to contact the root nameservers. Forcing all Internet hosts to maintain the most recent version of this list would be difficult from an operational point of view. To solve this problem, the designers of the DNS introduced a special type of DNS server : the DNS resolvers. A resolver is a server that provides the name resolution service for a set of clients. A network usually contains a few resolvers. Each host in these networks is configured to send all its DNS queries via one of its local resolvers. These queries are called recursive queries as the resolver must recurse through the hierarchy of nameservers to obtain the answer.

DNS resolvers have several advantages over letting each Internet host query directly nameservers. Firstly, regular Internet hosts do not need to maintain the up-to-date list of the IP addresses of the root servers. Secondly, regular Internet hosts do not need to send queries to nameservers all over the Internet. Furthermore, as a DNS resolver serves a large number of hosts, it can cache the received answers. This allows the resolver to quickly return answers for popular DNS queries and reduces the load on all DNS servers [JSBM2002].

The last component of the Domain Name System is the DNS protocol. The DNS protocol runs above both the datagram service and the bytestream services. In practice, the datagram service is used when short queries and responses are exchanged, and the bytestream service is used when longer responses are expected. In this section, we will only discuss the utilisation of the DNS protocol above the datagram service. This is the most frequent utilisation of the DNS.

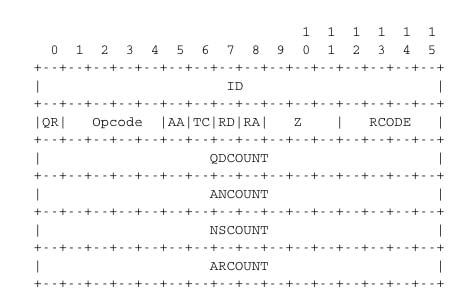

DNS messages are composed of five parts that are named sections in RFC 1035. The first three sections are mandatory and the last two sections are optional. The first section of a DNS message is its Header. It contains information about the type of message and the content of the other sections. The second section contains the Question sent to the name server or resolver. The third section contains the Answer to the Question. When a client sends a DNS query, the Answer section is empty. The fourth section, named Authority, contains information about the servers that can provide an authoritative answer if required. The last section contains additional information that is supplied by the resolver or server but was not requested in the question.

The header of DNS messages is composed of 12 bytes and its structure is shown in the figure below.

The ID (identifier) is a 16-bits random value chosen by the client. When a client sends a question to a DNS server, it remembers the question and its identifier. When a server returns an answer, it returns in the ID field the identifier chosen by the client. Thanks to this identifier, the client can match the received answer with the question that it sent.

The QR flag is set to 0 in DNS queries and 1 in DNS answers. The Opcode is used to specify the type of query. For instance, a standard query is when a client sends a name and the server returns the corresponding data and an update request is when the client sends a name and new data and the server then updates its database.

The AA bit is set when the server that sent the response has authority for the domain name found in the question section. In the original DNS deployments, two types of servers were considered : authoritative servers and non-authoritative servers. The authoritative servers are managed by the system administrators responsible for a given domain. They always store the most recent information about a domain. Non-authoritative servers are servers or resolvers that store DNS information about external domains without being managed by the owners of a domain. They may thus provide answers that are out of date. From a security point of view, the authoritative bit is not an absolute indication about the validity of an answer. Securing the Domain Name System is a complex problem that was only addressed satisfactorily recently by the utilisation of cryptographic signatures in the DNSSEC extensions to DNS described in RFC 4033. However, these extensions are outside the scope of this chapter.

The RD (recursion desired) bit is set by a client when it sends a query to a resolver. Such a query is said to be recursive because the resolver will recurse through the DNS hierarchy to retrieve the answer on behalf of the client. In the past, all resolvers were configured to perform recursive queries on behalf of any Internet host. However, this exposes the resolvers to several security risks. The simplest one is that the resolver could become overloaded by having too many recursive queries to process. As of this writing, most resolvers 9 only allow recursive queries from clients belonging to their company or network and discard all other recursive queries. The RA bit indicates whether the server supports recursion. The RCODE is used to distinguish between different types of errors. See RFC 1035 for additional details. The last four fields indicate the size of the Question, Answer, Authority and Additional sections of the DNS message.

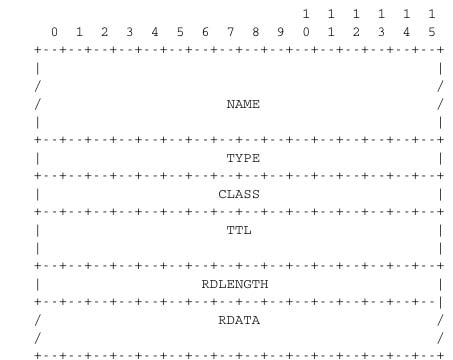

The last four sections of the DNS message contain Resource Records (RR). All RRs have the same top level format shown in the figure below.

In a Resource Record (RR), the Name indicates the name of the node to which this resource record pertains. The two bytes Type field indicate the type of resource record. The Class field was used to support the utilisation of the DNS in other environments than the Internet.

The TTL field indicates the lifetime of the Resource Record in seconds. This field is set by the server that returns an answer and indicates for how long a client or a resolver can store the Resource Record inside its cache. A long TTL indicates a stable RR. Some companies use short TTL values for mobile hosts and also for popular servers.

For example, a web hosting company that wants to spread the load over a pool of hundred servers can configure its nameservers to return different answers to different clients. If each answer has a small TTL, the clients will be forced to send DNS queries regularly. The nameserver will reply to these queries by supplying the address of the less loaded server.

The RD Length field is the length of the RData field that contains the information of the type specified in the Type field.

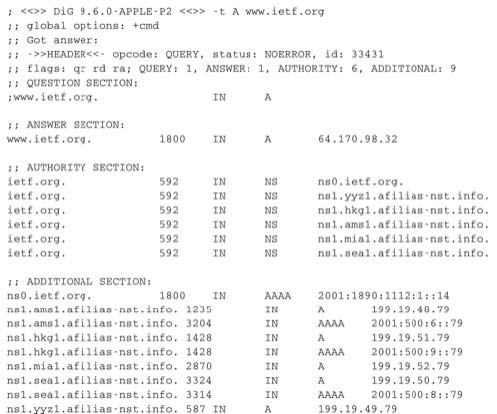

Several types of DNS RR are used in practice. The A type is used to encode the IPv4 address that corresponds to the specified name. The AAAA type is used to encode the IPv6 address that corresponds to the specified name. A NS record contains the name of the DNS server that is responsible for a given domain. For example, a query for the A record associated to the www.ietf.org name returns the following answer.

This answer contains several pieces of information. First, the name www.ietf.org is associated to IP address 64.170.98.32. Second, the ietf.org domain is managed by six different nameservers. Three of these nameservers are reachable via IPv4 and IPv6. Two of them are not reachable via IPv6 and ns0.ietf.org is only reachable via IPv6. A query for the AAAA record associated to www.ietf.org returns 2001:1890:1112:1::20 and the same authority and additional sections.

CNAME (or canonical names) are used to define aliases. For example www.example.com could be a CNAME for pc12.example.com that is the actual name of the server on which the web server for www.example.com runs.

The DNS is mainly used to find the IP address that correspond to a given name. However, it is sometimes useful to obtain the name that corresponds to an IP address. This done by using the PTR (pointer) RR. The RData part of a PTR RR contains the name while the Name part of the RR contains the IP address encoded in the in-addr.arpa domain. IPv4 addresses are encoded in the in-addr.arpa by reversing the four digits that compose the dotted decimal representation of the address. For example, consider IPv4 address 192.0.2.11. The hostname associated to this address can be found by requesting the PTR RR that corresponds to 11.2.0.192.in-addr.arpa. A similar solution is used to support IPv6 addresses, see RFC 3596.

An important point to note regarding the Domain Name System is its extensibility. Thanks to the Type and RDLength fields, the format of the Resource Records can easily be extended. Furthermore, a DNS implementation that receives a new Resource Record that it does not understand can ignore the record while still being able to process the other parts of the message. This allows, for example, a DNS server that only supports IPv4 to ignore the IPv6 addresses listed in the DNS reply for www.ietf.org while still being able to correctly parse the Resource Records that it understands. This extensibility allowed the Domain Name System to evolve over the years while still preserving the backward compatibility with already deployed DNS implementations.

- 2823 reads