note: This module has been peer-reviewed, accepted, and sanctioned by the National Council of the Professors of Educational Administration (NCPEA) as a scholarly contribution to the knowledge base in educational administration.

This article presents a protocol change leaders can use to navigate whole-system change in their school districts. The information describing the protocol will help change leaders in school districts and policymakers interested in whole-district change answer the question, “How do we transform our entire school system”? The protocol is called Step-Up-To-Excellence (SUTE; Duffy, 2002, 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c).

Every time SUTE is presented to an audience there is at least one person who calls out some “yes, buts” statements questioning whether the protocol is practical, do-able, or valid. Three “yes, buts” that are frequently heard and responses to them are found near the end of this article.

The Need for Whole-District Transformation

Rolling across America is a long train called “The School Improvement Express.” The triple societal engines of standards, assessment, and accountability are pulling it. The lead engine goes by the name “The No Child Left Behind Engine That Could.” The rolling stock is composed of school systems and a myriad of contemporary school improvement models, processes, and desirable outcomes. The train has once again come to a stop at a broad and deep abyss that goes by the name “The Canyon of Systemic School Improvement.” On the far side of the abyss lies the “Land of High Performance.” The riders on the train want to go there. In fact, they have wanted to go there for years but have failed to make the crossing, and so they keep returning here to the edge of the abyss to stare across with longing in their hearts wondering how they will ever traverse it.

Standing at the edge of this great abyss, some educators see a threat while others see an opportunity. Some see an impossible crossing, while others see just another puzzle to be solved. Meanwhile, the pressure in the three great “engines” for setting standards, assessing student learning, and holding educators accountable for results continues to build and shows no sign of dissipating. The “engineers” have their hands on the brakes but they can feel the pressure of the engine trying to edge the train forward, which feels like having one foot on the brake of a car while stepping on the gas with the other foot.

Even though the train has rolled across a lot of ground and although its passengers have done good things along the way, there they stand one more time looking out over the abyss wondering how in the world they will get to the other side. Some of those standing at the edge say, “Impossible, can't be done.” Others say, “We've been here before and failed then.” Still others stand there and theorize about the complexity of crossing such a canyon. “It's so hard to define the boundaries of the canyon. Just what is a system, what does it mean, is it this or is it that? We need this, this, this, and that or we'll never cross,” they suggest, but then they take no action to do what is needed. Still others, looking backward at the long train say, “What's behind us is the future. What we have done in the past is what we should continue to do.”

There is a significant and pressing need to cross the “canyon of systemic school improvement” (e.g., see Houlihan & Houlihan, 2005). One way to make the crossing is found in the Step-Up-To-Excellence (SUTE) protocol described below. Before examining the protocol, let us consider the traditional approach to managing change in organizations.

The Traditional Approach to Managing Change

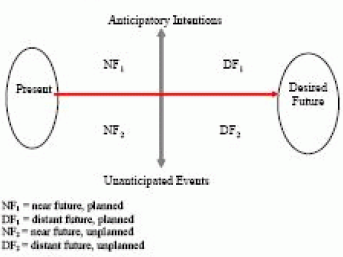

The traditional approach to managing change was developed by Kurt Lewin (1951). It is illustrated in the below figure. What Lewin said is that to change a system, people first envision a desired future. Then, they assess the current situation and compare the present to the future looking for gaps between what is and what is desired. Next, they develop a transition plan composed of long range goals and short term objectives that will move their system straight forward toward its desired future. Along the way there will be some unanticipated events that emerge, but it is assumed that the “strength” of anticipatory intentions (goals, objectives, strategic plans) will keep those unexpected events under control and thereby keep the system on a relatively straight change-path toward the future. The problem with this approach is that it does not work in contemporary organizations.

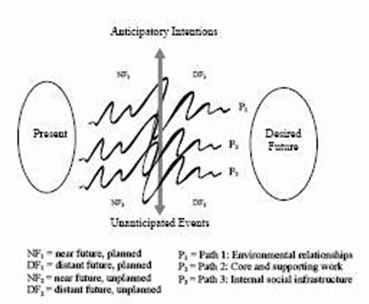

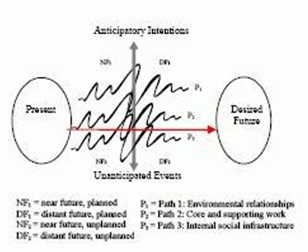

Instead of the “straightforward-to-the-future” as sumption represented in the Figure 6.2 , the complexities of con-temporary society and the pressures for rapid change, combined with an increasing number of unanticipated events and unintended consequences during change, have created three winding change-paths: Path 1: improve an organization's relationships with its environment; Path 2:improve its core and supporting work processes; and Path 3:improve its internal social infrastructure. These winding change-paths are illustrated in the Figure 6.3.

If change leaders assume that there is a single strategic path from the present to the future that is relatively straight forward when there are actually three winding paths, then as change leaders try to transform their system they will soon be off the true paths and lost. To see how they would be off the true paths (the three winding paths) trace your finger along the assumed straight path in the Figure 6.4. Wherever the straight path leaves the winding paths, you will be off course and lost. When of course and lost, people will revert back to their old ways, thereby enacting Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr's (n. d.) often quoted French folk wisdom, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

To move an entire school system along the three paths identified above, change leaders need a whole-system transformation protocol that will help them locate and navigate the three nonlinear paths to higher student, teacher and staff, and whole-district learning.

Three Paths to Improvement

Over the past 50 years a lot has been learned about how to improve entire systems. One of the core principles of whole-system change is that three sets of key organizational variables must be improved simultaneously (e.g., see Pasmore, 1988). These three sets of variables are characterized as change-paths in the protocol presented below. Let us examine the topography of each of these change-paths before exploring the change protocol.

Path 1: Improve a District's Relationship with Its External Environment

A school district is an open system. An open system is one that interacts with its environment by exchanging a valued product or service in return for needed resources. If change leaders want their district to become a high performing school system they need to have a positive and supporting relationship with stakeholders in their district's external environment. But they cannot wait until they transform their district to start working on these relationships. They need positive and supporting relationships shortly before they begin making important changes within their district. So, they have to improve their district's relationships with key external stakeholders as they prepare their school system to begin its transformation journey.

Path 2: Improve a District's Core and Supporting Work Processes

Core work is the most important work of any organization. In school districts, the core work is a sequenced instructional program (e.g., often a preK-12th grade instructional program) conjoined with classroom teaching and learning (Duffy, 2002; Duffy, 2003). Core work is maintained and enriched by supporting work. In school districts, supporting work roles include administrators, supervisors, education specialists, librarians, cafeteria workers, janitors, bus drivers, and others. Supporting work is important to the success of a school district, but it is not the most important work. Classroom teaching and learning is the most important work and it must be elevated to that status if a school system wants to increase its overall effectiveness.

When trying to improve a school system, both the core and supporting work processes must be improved. Further, the entire work process (e.g., preK-12th grade) must be examined and improved, not just parts of it (e.g., not just the middle school, not just the language arts curriculum, or not just the high school). One of the reasons the entire work process must be improved is because of a systems improvement principle expressed as “upstream errors flow downstream” (Pasmore, 1988). This principle reflects the fact that mistakes made early in a work process flow downstream, are compounded, and create more problems later on in the process; for example, consider a comment made by a high school principal when he first heard a description of this principle. He said, “Yes, I understand. And, I see that happening in our district. Our middle school program is being `dumbed-down' and those students are entering our high school program unprepared for our more rigorous curriculum. And, there is nothing we can do about it.” Upstream errors always flow downstream.

Improving student learning is an important goal of improving the core and supporting work processes of a school district. But focusing only on improving student learning is a piecemeal approach to improvement. A teacher's knowledge and literacy is probably one of the more important factors influencing student learning. So, taking steps to improve teacher learning must also be part of any school district's improvement efforts to improve student learning.

Improving student and teacher learning is an important goal of improving work in a school district. But this is still a piecemeal approach to improving a school district. A school district is a knowledge-creating organization and it is, or should be, a learning organization. Professional knowledge must be created and embedded in a school district's operational structures and organizational learning must occur if a school district wants to develop and maintain the capacity to provide children with a quality education. So, school system learning (i.e., organizational learning) must also be part of a district's improvement strategy to improve its core and supporting work.

Path 3: Improve a District's Internal “Social Infrastructure”

Improving work processes to improve learning for students, teachers and staff, and the whole school system is an important goal but it is still a piecemeal approach to change. It is possible for a school district to have a fabulous curriculum with extraordinarily effective instructional methods but still have an internal social “infrastructure” (which includes organization culture, organization design, communication patterns, power and political dynamics, reward systems, and so on) that is de-motivating, dissatisfying, and demoralizing for teachers. De-motivated, dissatisfied, and demoralized teachers cannot and will not use a fabulous curriculum in remarkable ways. So, in addition to improving how the work of a district is done, improvement efforts must focus simultaneously on improving a district's internal social “infrastructure.”

The social infrastructure of a school system needs to be redesigned at the same time the core and supporting work processes are redesigned. Why? Because it is important to assure that the new social infrastructure and the new work processes complement each other. The best way to assure this complementarity is to make simultaneous improvements to both elements of a school system.

Hopefully, this three-path metaphor makes sense because the principle of simultaneous improvement is absolutely essential for effective system wide improvement (e.g., see Emery, 1977; Pasmore, 1988; Trist, Higgin, Murray, & Pollack, 1963). In the literature on systems improvement this principle is called joint optimization (Cummings & Worley, 2001, p. 353).

The Change Protocol: Step-Up-To-Excellence

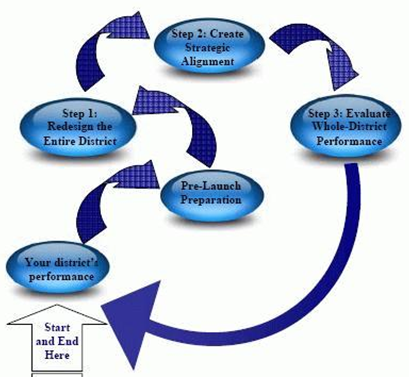

Step-Up-To-Excellence (SUTE) is a whole-system transformation protocol especially constructed to help educators navigate the three paths toward whole-district transformation described above. This protocol com-bines for the first time proven and effective tools for whole-system improvement in school districts. Although these tools have been used singly and effectively for more than 40 years, they never have been combined to provide educators with a comprehensive, unified, systematic, and systemic protocol for redesigning entire school systems. The protocol is illustrated in the Figure 6.5.

SUTE is an innovative approach to creating and sustaining whole-system change in school districts. The change navigation protocol for implementing SUTE is described below. The protocol also links the theory of system wide organization improvement to proven tools for improving whole-systems and innovative methods for improving knowledge work. The phrase “proven tools” is not used frivolously. Tools integrated into SUTE have years of research and successful experience supporting their effectiveness. Two of these tools are Merrelyn Emery's Search Conference and Participative Design Workshop (Emery, 2006; Emery & Purser, 1996). A third tool that can be used instead of Emery's Search Conference is Weisbord and Jano's Future Search (in Schweitz & Martens with Aronson, 2005). A fourth tool is Harrison Owen's (1991, 1993) Open Space Technology. Elements of Dannemiller's Real Time Strategic Change (Dannemiller & Jacobs, 1992; Dannemiller-Tyson Associates, 1994) also have been blended into SUTE. Another set of tools incorporated into SUTE is from field of socio-technical systems (STS) design (e.g., van Eijnatten, Eggermont, de Goffau, & Mankoe, 1994; Pava, 1983a, 1983b).

Concepts and Principles Underpinning the SUTE Change Protocol

The unit of change for SUTE is an entire school system. This is an essential principle that forms the foundation of the SUTE protocol. The rationale for this principle can be drawn from teachings as old as the Bible where it was said, “As a body is one though it has many parts, and all the parts of the body, though many, are one body . . .If one part suffers, all the parts suffer with it; if one part is honored, all the parts share the joy” (1 Corinthians 12:12, 12:26). In much the same way, a school district is one system even though it is composed of many “parts.”

Although a school district is a system, the dominant approach to improving school districts is not systemic; rather, it is based on the principles of school-based management, which aims to improve one-school-at-a-time or one-program-at-a-time. Many of the best current and past education reform programs are limited in their scope of impact because they focus almost exclusively on changing what happens inside single schools and classrooms. This focus is not misguided. Schools and classrooms are where changes need to happen. School-based reform must continue. But, it needs to evolve to a different level because this focus is insufficient for producing widespread, long-lasting district-wide improvements.

The one-school-at-a-time approach creates piecemeal change. Piecemeal change inside a school district is an approach that at its worst does more harm than good and at its best is limited to creating pockets of “good” within school districts. When it comes to improving schooling in a district, however, creating pockets of good is not good enough. Whole school systems need to be improved.

If history offers any guidance for the future, one consequence of piecemeal change is that good education change programs that attempt to improve student learning will come and go, largely with mediocre results. When there is success, it will be isolated in “pockets of excellence.” Regarding this phenomenon, Michael Fullan (in Duffy, 2002) said,

What are the `big problems' facing educational reform? They can be summed up in one sentence: School systems are overloaded with fragmented, ad hoc, episodic initiatives [with] lots of activity and confusion. Put another way, change even when successful in pockets, fails to go to scale. It fails to become systemic. And, of course, it has no chance of becoming sustained. (p. ix)

Many believe that change in school districts is piecemeal, disconnected, and non-systemic. Jack Dale, Maryland's Superintendent of the Year for 2000 and the current superintendent

of the Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia commented on the problem of incremental, piecemeal change. He said piecemeal change occurs as educators respond to demands from a school

system's environment. He asked (in Duffy, 2002),

How have we responded? Typically, we design a new program to meet each emerging need as it is identified and validated.... The continual addition of discrete educational

programs does not work.... Each of the specialty programs developed have, in fact, shifted the responsibility (burden) from the whole system to expecting a specific program to solve the

problem. (p. 34)

Another person who commented on the ineffectiveness of piecemeal change was Scott Thompson, Assistant Executive Director of the Panasonic Foundation, a sponsor of district-wide change. In talking about piecemeal change, Thompson (2001) said, “The challenge [of school improvement], however, cannot be met through isolated programs; it requires a systemic response. Tackling it will require fundamental changes in the policies, roles, practices, finances, culture, and structure of the school system” (p. 2).

Regarding the inadequacies of the one-school-at-a-time approach, Lew Rhodes (1997), a former assistant executive director for the American Association of School Administrators said,

It was a lot easier 30 years ago when John Goodlad popularized the idea of the school building as the fundamental unit of change.... But now it is time to question that assumption not because it is wrong but because it is insufficient. Otherwise, how can we answer the question: `If the building is the primary unit at which to focus change efforts, why after 30 years has so little really changed?' (p. 19)

Focusing school improvement only on individual school buildings and classrooms within a district also leaves some teachers and children behind in average and low performing schools. Leaving teachers and students behind in average or low performing schools is a subtle, but powerful, form of discrimination. School-aged children and their teachers, families, and communities deserve better. It is morally unconscionable to allow some schools in a district to excel while others celebrate their mediocrity or languish in their desperation. Entire school districts must improve, not just parts of them.

There are two additional consequences of piecemeal change within school systems. First, piecemeal improvements are not and never will be widespread; second, piecemeal improvements are not and cannot be long-lasting. Widespread and long-lasting improvements require district-wide change led by courageous, passionate, and visionary leaders who recognize the inherent limitations of piecemeal change and who recognize that a child's educational experience is the cumulative effect of his or her “education career” in a school district.

The SUTE Change Protocol

SUTE is a three-step process preceded by a Pre-Launch Preparation phase and it is cyclical. 1The SUTE journey proceeds as follows:

- Pre-Launch Preparation

- Step 1: Redesign the entire school district

- Step 2: Create strategic alignment

- Step 3: Evaluate the performance of the entire school district

- Recycle to Pre-Launch Preparation

Pre-Launch Preparation

One of the most common reasons for the failed transformation efforts is the lack of good preparation and planning (Kotter, 1996). What happens during the preparation phase will significantly influence the success (or failure) of a district's transformation journey. So change leaders have to take the time to do these activities in a carefully considered manner. Quick fixes almost always eventually fail even though they may produce an immediate illusion of improvement.

The early Pre-Launch Preparation activities are conducted by the superintendent of schools and several hand-picked subordinates. All of these people comprise a “pre-launch team.” The superintendent may also wish to include one or two trusted school board members on this small starter team. It is also important to know that this small team is temporary and it will not lead the transformation journey that will be launched later in the preparation phase. This team only has one purpose to complete early activities to prepare the district for whole-system change.

There are many pre-launch preparation activities (see Duffy 2003, 2004c). They are all important. Some of the tasks should be initiated simultaneously (e.g., building political support among internal and external stakeholders while simultaneously scouting-out “best-practices” and funding sources to support the change process). Others need to be sequenced (e.g., assess and document the need for the district to change followed by the development of clear and powerful public relations messages about that need followed by a Community Engagement Conference followed by a District Engagement Conference).

Research (Sirkin, Keenan & Jackson, 2005) suggests there are four key factors that affect the success or failure of a transformation effort. These factors must be addressed during the Pre-Launch Preparation phase. Sirkin, Keenan and Jackson call these the “hard factors of change.” They are:

- Duration: the amount of time needed to complete the transformation initiative;

- Integrity: the ability of the change leadership teams to complete the transformation activities as planned and on time; which is directly affected by the team members' knowledge and skills for leading a transformation journey;

- Commitment: the level of unequivocal support for the transformation demonstrated by senior leader-ship as well as by employees;

- Effort: the amount of effort above and beyond normal work activities that is needed to complete the transformation.

Let us look at each of these factors more closely.

- Hard Factor #1: Duration. There is a common assumption that transformation efforts that require longer timelines are more likely to fail. Contrary to this common assumption Sirkin, Keenan, and Jackson's (2005) research suggests that long-term transformation efforts that are evaluated frequently are more likely to succeed than short-term projects that are not evaluated. It seems that the frequent use of formative evaluation during a transformation journey has a significant positive effect on the success of that journey.

- Hard Factor #2: Integrity. The question this factor addresses is “Can we rely on the change leadership teams that we create to facilitate the transformation journey effectively and successfully”? The importance of the answer to this question cannot be understated. The success of a district's transformation journey will be directly affected by the knowledge and skills of the people who staff the various change leadership teams that must be chartered and trained to provide change leadership. Change leaders need to get their district's best people on these teams, where “best” means smart, articulate, influential, and unequivocally committed to the transformation goals.

- Hard Factor #3: Commitment. Transformational change must be led from the top of a school district. The superintendent must not only provide verbal support for the transformation but he or she must also demonstrate behavioral support by participating in transformation activities.

Initial commitment to the transformation must also be present among approximately 25% of a district's faculty and staff. This cadre of supporters is called a “critical mass.” Block's (1986) discussion of political groups in organizations offered a useful way to identify who does and does not support leadership in organizations. His model can be modified to identify who does and does not support a school district's transformation journey.

Block used two dimensions (vertical and horizontal) to identify five political groups in organizations. When adapted to support a district's transformation journey, the vertical axis of his model would be the level of agreement about the district's transformation goals. The horizontal axis would represent the level of trust between and among people in the district. The intersection of these two axes creates five political groups:

Allies: high goal agreement and high trust;

Opponents: low goal agreement, but high trust it may be possible to

convert these people into allies; Bedfellows: high goal agreement, but low to moderate levels of trust; Adversaries: low agreement on goals and low trust who will probably never be

converted to allies or bedfellows. Fencesitters: these people cannot

decide where they stand on the goal of transforming their school district. They usually have a wait and see attitude toward the changes that are being proposed.

Block offered political strategies for working with each group. These strategies can be used during the Pre-Launch Preparation phase to build internal and external political support for a district's transformation journey.

- Hard Factor #4: Effort. When planning the transformation of a school district change leaders some-times do not realize or do not know how to deal with the fact that faculty and staff are already busy with their day-to-day responsibilities (see objection #3 at the end of this article). If in addition to these existing responsibilities faculty and staff are asked to join the change leadership teams that are required to transform their district their level of resistance toward the transformation journey will increase.

Sirkin, Keenan and Jackson (2005, p. 6) suggested that ideally the workload of key employees (i.e., those who have direct change leadership responsibilities) should not increase more than 10% during a transformation effort. Beyond the 10% limit resources for change will be overstretched, employee morale will plummet, and interpersonal and inter-group conflict will increase. Therefore, decisions must be made about how to manage the workload of the people who are invited to join the change leadership teams that are formed for the SUTE journey.

Making a launch/do not launch decision. At some point the pre-launch team will decide if their school sys-tem is ready or not ready to launch a full-scale transformation journey; that is, they will make a “launch/don't launch” decision. If a launch decision is made, then a new leadership team is chartered and trained to pro-vide strategic leadership for the duration of the transformation journey. This team, because of its purpose, is called a Strategic Leadership Team and it is staffed by the superintendent and several others, including teachers and building administrators appointed to the team by their peers (not by the superintendent). This team also appoints and trains a Change Navigation Coordinator who provides daily, tactical leadership for the SUTE journey.

Near the end of the Pre-Launch Preparation phase, the Strategic Leadership Team and Change Navigation Coordinator organize and conduct a 3-day Community Engagement Conference that can bring into a single room hundreds of people from the community who then self-organize into smaller discussion groups around topics related to the district's transformation effort. This conference is designed using Harrison Owen's (1991, 1993) Open Space Technology design principles. The results of this conference are used as front-end data for another large-group event for the district's faculty and staff. This event is called a District Engagement Conference.

The 3-day District Engagement Conference is a strategic planning conference that brings the whole district into one room. This conference uses the design principles of Weisbord and Janoff's Future Search (in Schweitz & Martens with Aronson, 2005) or Emery's (2006) Search Conference (either set of principles will work for this conference). Bringing the whole district into the room, however, does not mean that every single person who works in the district participates in the conference. Instead, the Strategic Leadership Team and Change Navigation Coordinator ask each department, team, and unit within the district to send at least one person to participate in the conference. In this way, the whole system is represented in the conference room. The outcome of this conference is a new strategic framework for the district that includes a new mission, vision, and strategic plan; as well as parameters for guiding the transformation journey.

At the completion of the District Engagement Conference the Strategic Leadership Team and Change Navigation Coordinator organize the district into academic clusters (e.g., a cluster can be one high school and all the middle and elementary schools that feed into it), a cluster for the central administration staff, and a cluster for all other supporting work units. They also charter and train a Cluster Design Team for each cluster.

As stated earlier, the unit of change for SUTE is an entire school system rather than individual schools within a system. Although the entire system is the unit of change the SUTE journey is navigated by organizing the system into academic clusters, a cluster for the central administration, and a cluster for all nonacademic supporting work units. The academic clusters must include at least one school-based administrator and one teacher from each level of schooling within the cluster (e.g., in a preK-12th grade cluster there should be one administrator and one teacher from the elementary, middle, and secondary levels of schooling). This membership formula assures that the entire instructional program within an academic cluster is represented.

One cluster is also formed for the central office staff. This cluster includes all the functions housed in the central administration unit. Finally, there is cluster formed for the nonacademic supporting work units (e.g., cafeteria, building and grounds maintenance, and transportation).

All of these clusters are formed to facilitate the district's transformation journey. Each cluster has a Cluster Design Team that is trained in the principles of whole-system change. Each team guides the SUTE transformation journey within its respective cluster. The daily work of all the Cluster Design Teams will be coordinated by the Change Navigation Coordinator. The Strategic Leadership Team provides broad strategic oversight of the teams and the coordinator.

Step 1: Redesign the Entire School District

Navigating whole-system change requires simultaneous improvements along three paths:

- Path 1: Improve the district's relationship with its external environment, which improves relationships with key external stakeholders.

- Path 2: Improve the district's core and supporting work processes (core work is teaching and learning; supporting work includes secretarial work, administrative work, cafeteria work, building maintenance work, and so on).

- Path 3: Improve the district's internal social infrastructure (which includes organization design, governance, policies, organization culture, reward systems, job descriptions, communication, and so on.)

Near the beginning of Step 1, the Cluster Design Teams collaborate with the Change Navigation Coordinator to organize their respective clusters to begin the transformation journey. They do this by chartering Site Design Teams within each school building inside the academic clusters, within the central office cluster, and within the supporting work unit cluster. These Site Design Teams are staffed with highly regarded faculty and staff who do the daily work of teaching children, managing their administrative units, or providing support services. The people on these teams will be the ones who create innovative and powerful ideas for improving their building or work unit's 1) relationships with the external environment; 2) work processes; and 3) internal social infrastructure. This is an important principle because the field of systemic change believes that the people who actually do the work are the people best qualified to improve it (Emery, 1977; Emery, 2006; Emery & Purser, 1996; Weisbord, 2004).

The Site Design Teams are formed early in Step 1 and they receive training on principles of whole-system change. This training is provided by the Change Navigation Coordinator and the Cluster Design Teams in collaboration with an external consultant. At the completion of the training on whole-system change, each of the academic Cluster Design Teams organizes a Cluster Engagement Conference. These conferences are designed in the same way as the earlier District Engagement Conference by using Weisbord and Janoff's (in Schweitz & Martens with Aronson, 2005) Future Search principles or Emery's (2006) Search Conference principles. The central office and supporting work unit clusters will have a similar conference later in the transformation journey.

The Cluster Engagement Conferences are 3-day events. Each Cluster Design Team invites all of the Site Design Teams within its cluster to participate in the conference. The purpose of the conference is to create a “fuzzy” idealized design (Ackoff, 2001; Lee & Woll, 1996; Reigeluth, 1995) for each cluster. The idealized design must be aligned with the district's new strategic framework (mission, vision, and strategic goals) that was created earlier during the District Engagement Conference. The idealized design must also frame in broad terms how each cluster will make simultaneous improvements along three change-paths: Path 1 - relationships with external stakeholders; Path 2 - its work processes; and Path 3 - its internal social infrastructure.

The Cluster Design Conferences are quickly followed by a Redesign Workshop for each cluster. The Cluster Design Team organizes this three-day event for all of the Site Design Teams within its cluster. All members of the Site Design Teams participate in these workshops. The Redesign Workshops are organized using Emery's (2006) principles for designing Participative Design Workshops. The outcome of these three-day events is a proposal for transforming each cluster and every school within each cluster. These proposals contain specific, actionable ideas for making simultaneous improvements along the three change-paths identified earlier (i.e., each cluster's environmental relationships, work processes, and internal social infrastructure).

The number of change proposals will vary depending on the number of academic clusters within a district. It is appropriate and acceptable for each cluster to have different ideas for making improvements within their clusters as along as the ideas are clearly aligned with the district's grand vision and strategic framework. Allowing faculty and staff within each cluster to create innovative, but different, ideas for making improvements within their cluster is an example of applying the principle of equifinality (Cummings & Worley, 2001) to empower and enable the people who actually do the work of the district to make changes that make sense to them.

Although each cluster is encouraged to create innovative ideas for making simultaneous improvements along the three change-paths for their cluster, all of these improvements must be unequivocally aligned with the district's grand vision and strategic framework. To assure this strategic alignment, the Strategic Leadership Team reviews and approves all of the redesign proposals. Items marked for rejection or put on hold for a later implementation date must be negotiated with the Cluster Design Teams that proposed them before those decisions are finalized. Items accepted for implementation become the final redesign proposal for each academic cluster.

Now it is time for the central office and supporting work units to join the transformation journey. The core work of the district is classroom teaching and learning. The core work process is embedded in the academic clusters that just completed their redesign activities (Cluster Engagement Conferences followed by Redesign Workshops). To be an effective district, all other work in the school system must be aligned with and supportive of the district's core work processes (i.e., classroom teaching and learning); therefore, the central office and supporting work units must be redesigned to clearly and unequivocally support the changes that were proposed for the academic clusters

The central office and supporting work units participate in the same redesign process that the academic clusters just completed; i.e., they participate in Cluster Engagement Conferences and Redesign Workshops. The major outcome of the Cluster Engagement Conference and Redesign Workshops for the central office is to transform that unit into a central service center that acts in support of the academic clusters and the schools within those clusters while simultaneously supporting the district's grand vision and strategic framework. The major outcome of the Cluster Engagement Conference and Redesign Workshops for the supporting work units is to devise ways in which the work of these units can best support the academic clusters and the individual schools within them while also supporting the district's grand vision and strategic framework.

The Strategic Leadership Team now has redesign proposals from each of the academic clusters, the central office cluster, and the supporting work unit cluster. These proposals are consolidated into a master redesign proposal for the entire school system, which is then submitted to the district's school board for review and approval.

Next, the Strategic Leadership Team and Change Navigation Coordinator have the challenging task of finding the money to implement the master change proposal. Earlier during the Pre-Launch Preparation phase the Strategic Leadership Team scouted-out funding opportunities by identifying some state and federal agencies or philanthropic organizations that could be sources of money to support their district's transformation journey. Now, they approach these agencies and organizations by submitting grant proposals requesting financial support.

Money from outside agencies is often characterized as “extra” money because it is above and beyond the money in a district's normal operating budget. Even though extra money may be needed to sustain the first cycle of a transformation journey, money to kick-start a transformation journey can be found in district's current operating budget using budget reallocation strategies. Further, future cycles of SUTE should also be funded by permanent dollars in a district's budget. Additional information about how to pay for systemic change is found near the end of this article and in Duffy (2003).

Once the district has “seed” money to kick-start the transformation journey, the Strategic Leadership Team distributes the financial, human, and technical resources to the Cluster Design Teams so they can implement their sections of the master redesign proposal. The Cluster Design Teams delegate implementation responsibilities to the Site Design Teams within their domain. The implementation activities are managed on a daily basis by the Site Design Teams in each building and work unit and coordinated by the respective Cluster Design Teams in collaboration with the Change Navigation Coordinator. The Strategic Leadership Team provides broad strategic oversight of the entire implementation phase.

Implementation of new ideas and practices will require the school system, all the clusters, all of the individual schools and work units, and all individual faculty and staff to move through a learning curve, which always starts with a downhill slide in individual and organizational performance followed by an upward climb toward excellence (this learning curve is characterized as the “first down, then up” principle. Organizational Learning Networks (OLN) can facilitate and support the “first down, then up” experience. OLNs are informal communities of practice that focus learning on issues, problems, or opportunities related to the implementation of a district's master redesign proposal. They can be designed using Dufour and Eaker's (1998) principles for organizing learning communities. To facilitate the development and dissemination of professional knowledge throughout the school system, the OLNs are required to share their learning with everyone in the district.

Most large-scale change efforts fail during the implementation period; especially if the change timeline is long and if the transformation activities and outcomes are not periodically evaluated (Sirkin, Keenan, & Jackson, 2005). Because of the possibility of failure it is important for change leaders to design and facilitate On-Track Seminars. On-Track Seminars are specially designed seminars that engage faculty and staff in periodic evaluative inquiry (Preskill & Torres, 1998) about the change process and its outcomes. The formative evaluation data from the seminars are used to keep the transformation journey on course toward the district's grand vision and strategic goals. These seminars also:

- Facilitate individual, team and district-wide learning;

- Educate and train faculty and staff to use inquiry skills;

- Create opportunities to model collaboration, cooperation and participation behaviors;

- Establish linkages between learning and performance; Facilitate the search for ways to create greater understanding of what affects the district's success and failure; and,

- Rely on diverse perspectives to develop understanding of the district's performance.

During the period of formative evaluation it is important to assess the quality of discontent among people working in the school system and among key external stakeholders. The quality of discontent is a diagnostic clue about the relative success of a school system's transformation journey. In less healthy organizations, people complain about little things - low-order grumbles. These gripes are manifestations of what Abraham Maslow (in Farson, 1996, p. 93) called deficiency needs. In successful organizations, people have high-order gripes that focus on more altruistic concerns. In very successful organizations, people engage in metagripes complaints about their need for self-actualization. When change leaders hear these meta-gripes they will know that their system is stepping up to excellence.

Step 2: Create Strategic Alignment

After redesigning the district as described above, step 2 invites change leaders and their colleagues to align the work of individuals with the goals of their teams, the work of teams with the goals of their schools and work units, the work of schools and work units with the goals of their clusters, and the work of clusters with the goals of the district. Combined, these activities create strategic alignment.

Creating strategic alignment accomplishes three things (Duffy, 2004c). First, it assures that everyone is working toward the same broad strategic goals and vision for the district. Second, it weaves a web of accountabilities that makes everyone who touches the educational experience of a child accountable for his or her part in shaping that experience. And third, it has the potential to form a social infrastructure that is free of bureaucratic hassles, dysfunctional policies, and obstructionist procedures that limit individual and team effectiveness. It is these dysfunctional hassles, policies, and procedures that cause at least 80% of the performance problems that we usually blame on individuals and teams (Deming, 1986).

Step 3: Evaluate Whole-District Performance

Finally, in Step 3, the performance of the entire transformed district is evaluated using principles of summative evaluation (e.g., Stufflebeam, 2002, 2003). The purpose of this level of evaluation is to measure the success of everyone's efforts to educate children within the framework of the newly transformed school system. Evaluation data are also reported to external stakeholders to demonstrate the district's overall success in achieving its transformation goals.

After change leaders and their colleagues work through all three steps of Step-Up-To-Excellence they then focus on sustaining school district improvement by practicing continuous improvement at the district, cluster, school, team, and individual levels of performance. Then, after a predetermined period of stability and incremental improvements, they “step-up” again by cycling back to the Pre-launch Preparation Phase. Achieving high-performance is a lifelong journey for a school district.

In Anticipation of “Yes, Buts”

Whenever Step-Up-To-Excellence is presented to an audience predictably three key objections are voiced. These common objections and responses to them are presented below. It is very important for change leaders and school public relations specialists to anticipate objections to whole-system change and then prepare well-crafted messages that preempt the objections. By anticipating and preempting the objections, initial resistance to change can be significantly reduced. Further, the best time to anticipate and preempt objections is during the Pre-Launch Preparation phase of SUTE.

Objection #1: “Yes, This Is An Interesting Idea. But Where Is This Being Used”?

One of the greatest “innovation killers” in the history of mankind is captured in the question, “Where is this being used? Or, its corollary, “Who else is doing this?” Can you imagine Peter Senge (1990) being asked this question when he first proposed his 5th Discipline ideas; or perhaps Morris Cogan (1973) when he first described the principles of Clinical Supervision?

New ideas, by definition, are not being used anywhere, but they want to be used. However, being the first at doing anything, especially doing something that requires deep and broad change demands a high degree of leadership courage, passion, and vision. Many change leaders in education do indeed have the requisite courage, passion, and vision to be the first to try innovative ideas for creating and sustaining whole-system improvement, but they do not know how to lead whole-system change. These heroic leaders need a protocol especially designed to create and sustain whole-system change.

The most direct answer to the above objection is that Step-Up-To-Excellence is being used in the in the Metropolitan School District of Decatur Township in Indianapolis, Indiana. The protocol has been blended with a protocol created by Dr. Charles Reigeluth called the Guidance System for Transforming Education (GSTE). Dr. Reigeluth is also facilitating that systemic change effort 2. Although this is the direct answer to the objection, more needs to be said.

New methodologies to create and sustain district-wide change are not perfect and they never will be. Educators should not even try to find a perfect protocol. Instead, they need to examine new methods for navigating whole-district change, study how they work, find glitches in the processes, and search for logical flaws in the reasoning behind the methods. Then, assuming that a method is based on sound principles for improving whole systems, educators should then think about how they might correct the flaws to make the method work for their districts.

Some people read about whole-district change and exclaim, “Impossible”! Impossible is what some people think cannot be done until someone proves them wrong by doing it. Whole-district change not only “is-possible,” but it is being done successfully in school systems throughout the United States; e.g., in the Baldrige award-winning school districts of Chugach Public Schools in Anchorage, Alaska; the Pearl River School District in New York; and the Jenks Public Schools in Oklahoma. Other districts engaged in district-wide change were described in a research study by Togneri and Anderson (2003). The districts in that study were:

- Aldine Independent School District, Texas

- Chula Vista Elementary School District, California

- Kent County Public Schools, Maryland Minneapolis Public Schools,

- Minnesota

- Providence Public Schools, Rhode Island

The improvements these districts experienced were guided by many of the principles that underpin SUTE. So, if educators read about a protocol that seems impossible, they should ask, “If other school districts are using ideas and principles like these, why can't we?”

Some educators and policymakers will read about whole-district change and say, ‘Impractical.” Not only are the core principles and change-tools based on these principles practical, many of them are proven to work in school districts and other organizations throughout the United States. So, if and when educators and policymakers think that trying to improve an entire school system is impractical they should ask, “If other school districts have used these principles effectively, why can't we?”

Some people will read this article and proclaim, “Wow, these ideas are really far out. They are way outside the box.” It is my hope that readers will say this. If they do, this means I have succeeded in offering them some innovative ideas to think about and apply. And, if and when they see something that seems “way outside the box,” they should ask, “If this idea is outside the box, what box are we in?” and, “Do we want to stay inside this box of ours?”

Objection #2: “Yes, This Is A Nice Idea. But, How Do We Pay for This”?

The second biggest innovation killer in the world is found in the question, “How do we pay for this”? Unlike traditional reform efforts, whole-district change cannot be sustained solely through small increases in operating budgets, nor can it be sustained with “extra” money from outside the district. Because whole-system transformation touches all aspects of a school district's core operations, it imposes significant resource requirements on a district and demands a rethinking of the way current resources are allocated, as well as some creative thinking about how to use “extra” money that will be needed to jump start systemic reform.

Because there seems to be a scarce amount of literature on financing whole-district change, innovative, ground-level tactics, methods, and sources are needed to help educators find the financial resources they need to transform their school systems into high-performing organizations of learners. What follows are some insights about how to do this (these insights are explored more deeply in Duffy, 2003).

Below, you will find a brief discussion of some fundamental principles that are important for financing whole-district change. 3Many of these principles are advocated by school finance experts (e.g., Cascarino, 2000; Clune, 1994a; Keltner, 1998; Odden, 1998). The fundamental principles are:

- Think creatively about securing resources. Instead of saying “We can't do this, because . . . say, ”We can do this. Let's be creative in figuring out how?”;

- Develop a new mental model for financing school system improvement that helps change leaders think outside the box for creating innovative solutions to their resource allocation challenges;

- Embed the resources to support a whole-district improvement protocol in a school district's organization design and its normal operational budget;

- Develop a new mental model for financing school system improvement that helps change leaders create innovative solutions to resource allocation challenges (Odden, 1998);

- Fund whole-system improvement in the same way that a core program or activity is funded; i.e., with real dollars that are a permanent part of a school district's budget;

- Reallocate current operating money to support whole-district improvement (Keltner, 1998);

- Over time, reduce “extra” resources for whole-district improvement to near zero while increasing internal resources to support systemic improvement;

- As needed, combine federal funds in innovative ways to directly support district-wide improvements in teaching and learning (see Cascarino, 2000, p. 1);

- Focus thinking on financing for adequacy rather than on financing for equity (see Clune, 1994a, 1994b);

- When seeking outside money, make sure that the requirements and goals of the funding agency do not conflict or constrain the vision and strategic direction of the district's transformation journey; and,

- Employ superior communication skills so all stakeholders recognize the true purpose of a district's budget reallocation strategy, how it will work, and what the benefits will be.

Objection #3: Yes, Nice Idea. But, We Can Not Stop Doing What We Are Doing

Another important and significant obstacle to gaining support for whole-system change is that school districts have a core mission; i.e., they must provide children with approximately 180 days of classroom teaching and learning. Given the complexity of whole-system change and given the time required to plan and implement this kind of change, some educators and policymakers will object by saying, “Nice idea, but we can't stop doing what we're doing to participate in this kind of change process. We have to show up each day and teach kids.”

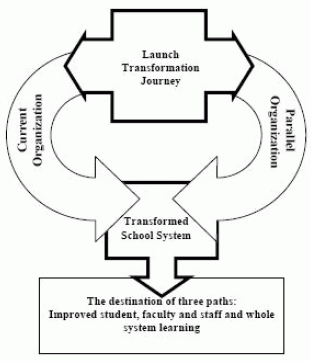

Of course, this objection is based on the realities of life in school systems. That is why it is so difficult to respond to this objection. But there is a response and it is derived from the experiences of real people making real changes in complex organizations with core missions that cannot be ignored. The response is that the Strategic Leadership Team and Change Navigation Coordinator must create a parallel organization after the launch decision is made during the Pre-Launch Preparation Phase.

The concept of parallel organizations is from the fields of organization theory and design and systemic change (e.g., Stein & Moss Kanter, 2002). A parallel organization, which is sometimes called a “parallel learning structure” (Human Resource Development Council, date unknown) is a change management structure.

A parallel organization is created during the Pre-Launch Preparation Phase of SUTE and it is represented by the collection of change navigation teams and change processes that are temporarily established to transform an entire school system. A simple illustration of this concept is found in the Figure 6.6.

The parallel organization is created by temporarily “transferring” carefully selected and trained educators into the parallel organization, which is constructed using the various change leadership teams. These people then create the new system.

Educators not transferred into the parallel organization continue to operate the current school system, thereby helping the district to achieve its core mission; i.e., educating children. Even though they are performing within the boundaries of the current system these educators are participating in Organization Learning Networks to help them learn the new knowledge and skills that they will need to perform successfully in the transformed school system.

In Step 1 of the SUTE protocol a master redesign proposal is created. At some point during Step 1 that proposal is implemented. As it is implemented the “old” system is transformed into the “new” system and the district continues to achieve its core mission, but it does so within the framework of a transformed system.

Conclusion

New change theory is based on the concept of flux. It recognizes that change is nonlinear and requires school districts to function at the edge of chaos as educators seek controlled disequilibrium to create innovative opportunities for improvement. New change theory tells us that to improve the performance level of a school district the system must first move downhill before it can move up to a higher level of performance. New change theory requires school districts to use a networked social infrastructure where innovations are grown from within and used to create whole-district change. New change theory requires a simultaneous ability to anticipate the future and respond quickly to unanticipated events. New change theory requires a protocol specifically designed to enact the concepts and principles that are part of the theory.

New change theory also requires change leadership that is distributed throughout a school district change leaders who are courageous, passionate and visionary and who use their power and political skills in ethical ways. Leaders like this are priceless and absolutely necessary. Leaders of this class work their magic by helping others to see the invisible, to do the seemingly impossible, and to create new realities heretofore only imagined. Creating world-class school districts that produce stunning opportunities for improving student, faculty and staff, and whole system learning can only be done under the stewardship of these kinds of leaders.

Leading whole-system change is not for the timid, the uninspired, or the perceptually nearsighted. It requires personal courage, passion, and vision. It is my hope that change leaders reading this article will find in these pages the key that unlocks or reinforces their personal courage, passion, and vision to lead this kind of large-scale effort. If they do step forward to accept that mission, they need to know that they step forward into a world that is not fully illuminated by research findings, a world that is a minefield of socio-political warfare and turf-battles, and into a world where they will often suffer emotional pain and feelings of betrayal by those they thought loyal. They may even lose their job. But, with courage, passion, and vision, I believe they can create a coalition of like-minded change leaders within and outside their district, and in collaboration with this coalition, together, they can endure the pain and betrayal, move forward toward their collective vision, and ultimately succeed in creating and sustaining previously unimagined opportunities for improving student, faculty and staff, and whole-system learning in their school district.

Feedback on results References

Ackoff, R. L. (2001). A brief guide to interactive planning and idealized design. Retrieved on March 19, 2006 at http://www.sociate.com/texts/acko_GuidetoIdealizedRedesign.pdf.

Block, P. (1986). The empowered manager: Positive political skills at work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cascarino, J. (2000, November). District Issues Brief - Many programs, one investment: Combining federal funds to support comprehensive school reform. Arlington, VA: New American Schools, Inc. Retrieved on October 12, 2003, at http://www.naschools.org/uploaded_les/Many Programs.pdf.

Clune, W. (1994a). The shift from equity to adequacy in school finance. Educational Policy, 8(4), 376-394.

Clune, W. (1994b). The cost and management of program adequacy: An emerging issue in education policy and finance. Educational Policy, 8(4), 365-375.

Cogan, M. L. (1973). Clinical supervision. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Cummings, T. G. & Worley, C. G. (2001). Organization development and change (7th ed.). Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing.

Dannemiller, K. & Jacobs, R. W. (1992). Changing the way organizations change: A revolution in common sense. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 28: 480-498.

Dannemiller-Tyson Associates (1994). Real time strategic change: A consultant's guide to large scale meetings. Ann Arbor, MI: Author.

Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study.

Deming, W. E. In Richmond, B. (2000). The `thinking' in systems thinking: Seven essential skills. The Toolbox Reprint Series. Williston, VT: Pegasus Communications, Inc.

Duffy, F. M. (1995). Supervising knowledge-work. NASSP Bulletin, 79 (573), 56-66.

Duffy, F. M. (1996). Designing high performance schools: A practical guide to organizational reengineering. Delray Beach, FL: St. Lucie Press.

Duffy, F. M. (2002). Step-Up-To-Excellence: An innovative approach to managing and rewarding performance in school systems. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education.

Duffy, F. M. (2003). Courage, passion and vision: A guide to leading systemic school improvement. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education and the American Association of School Administrators.

Duffy, F. M. (2004a, summer). The destination of three paths: Improved student, faculty and staff, and system learning. The Forum, 68(4), 313-324.

Duffy, F. M. (2004b). Navigating whole-district change: Eight principles for moving an organization upward in times of unpredictability. The School Administrator, 61(1), 22-25.

Duffy, F. M. (2004c). Moving upward together: Creating strategic alignment to sustain systemic school improvement. No. 1, Leading Systemic School Improvement Series. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education.

DuFour, R. & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. Bloomington, IN: National Education Service.

Eijnatten van, F., Eggermont, S., de Goffau, G., & Mankoe, I. (1994). The socio-technical systems design paradigm. Eindhoven, Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology.

Emery, F. E. (1977). Two basic organization designs in futures we are in. Leiden, Netherlands: Martius Nijhoff.

Emery, M. (2006). The future of schools: How communities and staff can transform their school districts. Leading Systemic School Improvement Series. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Emery, M. & Purser, R. E. (1996). The Search conference: A powerful method for planning organizational change and community action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Houlihan, G. T. & Houlihan, A. G. (2005). School performance: How to meet AYP and achieve long-term success. Rexford, NY: International Center for Leadership in Education.

Human Resource Development Council (date unknown). Parallel learning structures. Retrieved on March 26, 2006 at http://www.humtech.com/opm/grtl/ols/ols6.cfm .

Karr, J-B. A . (date unknown). Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr. Retrieved on March 17, 2006, at http://www.reference.com/browse/wiki/Jean-Baptiste_Alphonse_Karr.

Keltner, B. R. (1998). Funding comprehensive school reform. Rand Corporation. Retrieved on January 15, 2004 at http://www.rand.org/ publications/IP/IP175/ .

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Boston: MA. Harvard Business School Press.

Lee, T. & Woll, T. (1996, Spring). Design and planning in organizations. Center for Quality of Management Journal, 5 (1). Retrieved on March 19, 2006 at http://cqmextra.cqm.org/ cqmjournal.nsf/ reprints/ rp06900.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York: Harper and Row.

Maslow, A. in R. Farson (1996). Management of the absurd. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Odden, A. (1998, January). District Issues Brief: How to rethink school budgets to support school transformation. Arlington, VA: New American Schools. Retrieved on October 25, 2002, at http://www.naschools.org/uploaded_les/oddenbud.pdf.

Owen, H. (1991). Riding the tiger: Doing business in a transforming world. Potomac, MD: Abbott Publishing.

Owen, H. (1993). Open Space Technology: A user's guide. Potomac, MD: Abbott Publishing. Pasmore, W. A. (1988). Designing effective organizations: The socio-technical systems perspective. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Pava, C. H. P. (1983a, Spring). Designing managerial and professional work for high performance: A sociotechnical approach. National Productivity Review: 126-135.

Pava, C. H. P. (1983b). Managing new office technology: An organizational strategy. New York: The New Press.

Preskill, H. & Torres, R. T. (1998). Evaluative inquiry for learning in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Reigeluth, C. M. (1995). A conversation on guidelines for the process of facilitating systemic change in education. Systems Practice, 8 (3), 315-328.

Rhodes, L. A. (1997, April). Connecting leadership and learning: A planning paper developed for the American Association of School Administrators, Arlington, VA: AASA.

Schweitz, R. & Martens, K. with Aronson, N. (Eds.) (2005). Future Search in school district change: Connection, community, and results. Leading Systemic School Improvement Series, No. 3. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

Sirkin, H. L.; Keenan, P.; & Jackson, A. (2005, October). The hard side of change management. Harvard Business Review, 1-10.

Stein, B. A. & Kanter, R. M. (2002). Building the parallel organization: Creating mechanisms for permanent quality of work life. Retrievedon March 25, 2006 at http://www.goodmeasure.com/site/parallel%20org/index.htm .

Stufflebeam, D. L. (2002). CIPP evaluation model checklist: A tool for applying the fifth Installment of the CIPP Model to assess long-term enterprises. Retrieved on March 30, 2006 at http://www.wmich.edu/evalctr/checklists/cippchecklist.htm.

Stufflebeam, D. L. (2003). The CIPP model for evaluation. Retrieved on March 30, 2006 at http://www.wmich.edu/evalctr/pubs/CIPP-ModelOregon10-03.pdf.

Thompson, S. (2001,November). Taking on the “all means all” challenge. Strategies for School System Leaders on District-Level Change, 8 (2). Retrieved on March 1, 2005 at http://www.aasa.org/publications/strategies/Strategies_11-01.pdf.

Togneri, W. & Anderson, S. E. (2003). Beyond islands of excellence: What districts can do to improve instruction and achievement in all schools a leadership brief. Washington, DC: Learning First Alliance.

Trist, E. L., Higgin, G. W., Murray, H., & Pollack, A.B. (1963). Organizational choice. London: Tavis-tock.

Weisbord, M. R. (2004). Productive workplaces revisited: Dignity, meaning, and community in the 21st Century (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Wiley & Sons/Pfeiffer.

- 4201 reads