LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Explore the strict constructionist, or originalist, judicial philosophy.

- Explore the judicial activist philosophy.

- Learn about the modern origin of the divide between these two philosophies.

- Examine the evolution of the right to privacy and how it affects judicial philosophy.

- Explore the biographies of the current Supreme Court justices.

In the early years of the republic, judges tended to be much more political than they are today. Many were former statesmen or diplomats and considered being a judge to be a mere extension of their political activities. Consider, for example, the presidential election of 1800 between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Even by today’s heated standards of presidential politics, the 1800 election was bitter and partisan. When Jefferson won, he was in a position of being president at a time when not a single federal judge in the country came from his political party. Jefferson was extremely wary of judges, and when the Supreme Court handed down the Marbury v. Madison decision in 1803 declaring the Supreme Court the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution’s meaning, Jefferson wrote that “to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions is a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.” 1 A few years later, the first justice to be impeached, Samuel Chase, was accused of being overly political. His impeachment (and subsequent acquittal) started a trend toward nonpartisanship and political impartiality among judges. Today, judges continue this tradition by exercising impartiality in cases before them. Nonetheless, charges of political bias continue to be levied against judges at all levels.

In truth, the majority of a judge’s work has nothing to do with politics. Even at the Supreme Court level, most of the cases heard involve conflicts among circuit courts of appeals or statutory interpretation. In a small minority of cases, however, federal judges are called on to interpret a case involving religion, race, or civil rights. In these cases, judges are guided sometimes by nothing more than their own interpretation of case law and their own conscience. This has led some activists to claim that judges are using their positions to advance their own political agendas.

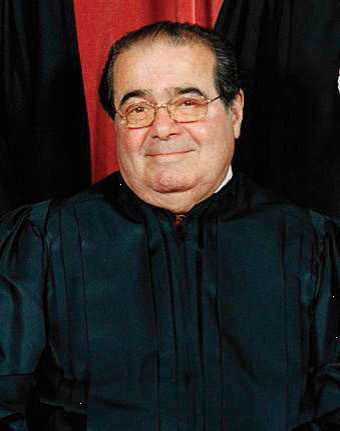

In general terms, judges are thought to fall into one of two ideological camps. On the politically conservative right, judges are described as either strict constructionists or originalists. Judges who adhere to this philosophy believe that social change is best left to the politically elected branches of government. The role of judges is therefore to strictly interpret the Constitution, and nothing more. Strict constructionists also believe that the Constitution contains the complete list of rights that Americans enjoy and that any right not listed in the Constitution does not exist and must be earned legislatively or through constitutional amendment. Judges do not have the power to “invent” a new right that does not exist in the Constitution. These judges believe in original meaning, which means interpreting the Constitution as it was meant when it was written, as opposed to how society would interpret the Constitution today. Strict constructionists believe that interpreting new rights into the Constitution is a dangerous exercise because there is nothing to guide the development of new rights other than a judge’s individual conscience. Justice Antonin Scalia, appointed by Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court in 1984, embodies the modern strict constructionist.

Hyperlink: Justice Antonin Scalia

Source: Photo courtesy of Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Antonin_Scalia,_SCOTUS_photo_portrait.jpg. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/24/60minutes/main4040290.shtml In 2008, Justice Antonin Scalia (Figure 2.7

"Justice Antonin Scalia") sat down with 60 Minutes to discuss a new book he wrote and his originalist judicial philosophy. Click the link to watch a portion of this fascinating interview with

one of the most powerful judges in the country.

On the politically liberal left are judges who are described as activist. Judicial activists believe that judges have a role in shaping a “more perfect union” as described in the Constitution and that therefore judges have the obligation to seek justice whenever possible. They believe that the Constitution is a “living document” and should be interpreted in light of society’s needs, rather than its historical meaning. Judicial activists believe that sometimes the political process is flawed and that majority rule can lead to the baser instincts of humanity becoming the rule of law. They believe their role is to safeguard the voice of the minority and the oppressed and to deliver the promise of liberty in the Constitution to all Americans. Judicial activists believe in a broad reading of the Constitution, preferring to look at the motivation, intent, and implications of the Constitution’s safeguards rather than merely its words. Judicial activism at the Supreme Court was at its peak in the 1960s, when Chief Justice Earl Warren led the Court in breaking new ground on civil rights protections. Although a Republican, and nominated by Republican President Eisenhower, Earl Warren became a far more activist judge than anyone anticipated once on the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Warren led the Court in the desegregation cases in the 1950s, including the one affecting the Little Rock Nine. The “Miranda” 2 warnings—familiar to nearly every American who has ever seen a police show or movie—come from Chief Justice Warren, as does the fact that anyone who cannot afford an attorney has the right to publicly funded counsel in most criminal cases.

Source: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress,http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c17121.

The modern characterization of judges as politically motivated can be traced to the Great Depression. Against cataclysmic economic upheaval, Americans voted for Franklin D. Roosevelt (Figure 2.8 "President Franklin Roosevelt") in record numbers, and they delivered commanding majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives to his Democratic Party. President Roosevelt vowed to alter the relationship between the people and their government to prevent the sort of destruction and despair wreaked by the Depression. The centerpiece of his action plan was the New Deal, a legislative package that rewrote the role of government, vastly increasing its size and its role in private commercial activity. The New Deal brought maximum working hours, the minimum wage, mortgage assistance, economic stimulus, and social safety nets such as Social Security and insured bank deposits. Although the White House and the Congress were in near-complete agreement on the New Deal, the Supreme Court was controlled by a slim majority known as the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” because of their dire warnings of the consequences of economic regulation. Three justices known as the “Three Musketeers”—Justice Brandeis, Justice Cardozo, and Justice Stone— opposed the Four Horsemen. In the middle sat two swing votes. The Four Horsemen initially prevailed, and one by one, pieces of President Roosevelt’s New Deal were struck down as unconstitutional reaches of power by the federal government. Frustrated, President Roosevelt devised a plan to alter the makeup of the Supreme Court by increasing the number of judges and appointing new justices. The “court-packing plan” was never implemented due to the public’s reaction, but nonetheless, the swing votes on the Supreme Court switched their votes and began upholding New Deal legislation, leading some historians to label their move the “switch in time that saved Nine.” During the public debate over the Supreme Court’s decisions on the New Deal, the justices came under constant attack for being politically motivated. The loudest criticism came from the White House.

Hyperlink: Fireside Chats

http://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/3309

One of the hallmarks of FDR’s presidency was his use of the radio to reach millions of Americans across the country. He regularly broadcast his “fireside chats” to inform and lobby the public. In this link, President Roosevelt complains bitterly about the Supreme Court, claiming that “the Court has been acting not as a judicial body, but as a policy-making body.” Do modern politicians make the same accusation?

The abortion debate is a good example of the politically charged atmosphere surrounding modern judicial politics. Strict constructionists decry Roe v. Wadeas an extremely activist decision and bemoan the fact that in a democracy, no one has ever had the chance to vote on one of the most socially controversial and divisive issues of our time. Roe held that a woman has a right to privacy and that her right to privacy must be balanced against the government’s interest in preserving human life. Within the first trimester of her pregnancy, her right to privacy outweighs governmental intrusion. Since there is no right to privacy mentioned in the Constitution, strict constructionists believe that Roe has no constitutional foundations to stand on.

Roe did not, however, declare that a right to privacy exists in the Constitution. A string of cases before Roe established that right. In 1965 the Supreme Court overturned a Connecticut law prohibiting unmarried couples from purchasing any form of birth control or contraceptive. 3 The Court reasoned that the First Amendment has a “penumbra of privacy” that must include the right for couples to choose if and when they want to have children. Two years later, the Supreme Court found a right to privacy in the due process clause when it declared laws prohibiting mixed-race marriages to be unconstitutional. 4 As a result of these decisions and others like them, the phrase “right to privacy” today is widely accepted as a form of litmus test for whether a judge (or judicial candidate) is a strict constructionist or activist.

- 3820 reads