LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand what crime is.

- Compare and contrast the differences between criminal law and civil law.

- Understand the constitutional protections afforded to those accused of committing a crime.

- Examine some common defenses to crime.

- Learn about the consequences of committing a crime.

- Explore the goals or purposes of punishment for committing a crime.

Imagine a bookkeeper who works for a physicians group. This bookkeeper’s job is to collect invoices that are due and payable by the physicians group and to process the payments for those invoices. The bookkeeper realizes that the physicians themselves are very busy, and they seem to trust the bookkeeper with the task of figuring out what needs to be paid. She decides to create a fake company, generate bogus invoices for “services rendered,” and send the invoices to the physicians group for payment. When she processes payment for those invoices, the fake company deposits the checks in its bank account—a bank account she secretly owns. This is a fraudulent disbursement, and it is just one of many ways in which crime occurs in the workplace. Check out Note 10.4 "Hyperlink: Thefts, Skimming, Fake Invoices, Oh My!" to examine several other common embezzlement schemes easily perpetrated by trusted employees.

Hyperlink: Thefts, Skimming, Fake Invoices, Oh My!

http://www.acfe.com/resources/view.asp?ArticleID=1

Think it couldn’t happen to you? Check out common schemes perpetrated by trusted employees in this article posted on the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners’ Web site.

When crime occurs in the workplace or in the context of business, the temptation might be to think that no one is “really” injured. After all, insurance policies can cover some losses. Sometimes people think that if the victims of embezzlement do not immediately notice the embezzlement, then they must not “need” the money anyhow, so no real crime has been committed. Of course, these excuses are just smoke screens. When an insurance company has to pay for a claim arising from a crime, the insurance company is injured, as are the victim and society at large. Similarly, the fact that wealthy people or businesses do not notice embezzlement immediately does not mean that they are not entitled to retain their property. Crime undermines confidence in social order and the expectations that we all have about living in a civil society. No crime is victimless.

A crime is a public injury. At the most basic level, criminal statutes reflect the rules that must be followed for a civil society to function. Crimes are an offense to civil society and its social order. In short, crimes are an offense to the public, and someone who commits a crime has committed an injury to the public.

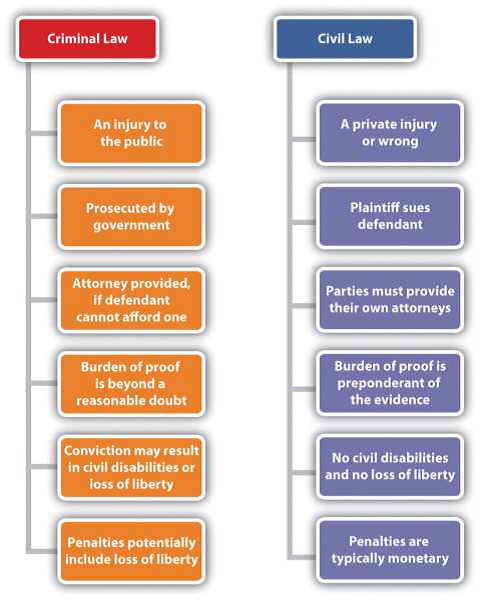

Criminal law differs from civil law in several important ways. See Figure 10.3 "Comparison between Criminal Law and Civil Law" for a comparison. For starters, since crimes are public injuries, they are punishable by the government. It is the government’s responsibility to bring charges against criminals. In fact, private citizens may not prosecute each other for crimes. When a crime has been committed—for instance, if someone is the victim of fraud—then the government collects the evidence and files charges against the defendant. When someone is charged with committing a crime, he or she is charged by the government in an indictment. The victim of the crime is a witness for the government but not for the prosecutor of the case. Note that our civil tort system allows a victim to bring a civil suit against someone for injuries inflicted on the victim by someone else. Indeed, criminal laws and torts often have parallel causes of action. Sometimes these claims carry the same or similar names. For instance, a victim of fraud may bring a civil action for fraud and may also be a witness for the state during the criminal trial for fraud.

In a criminal case, the defendant is presumed to be innocent unless and until he or she is proven guilty. This presumption of innocence means that the state must prove the case against the defendant before the government can impose punishment. If the state cannot prove its case, then the person charged with the crime will be acquitted. This means that the defendant will be released, and he or she may not be tried for that crime again. The burden of proof in a criminal case is the prosecution’s burden, and the prosecution must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. This means that the defendant does not have to prove anything, because the burden is on the government to prove its case. Additionally, the evidence must be so compelling that there is no reasonable doubt as to the defendant’s guilt. To be convicted of a crime, someone must possess the required criminal state of mind, or mens rea. Likewise, the person must have committed a criminal act, known as actus reus.

Compare this to the standard of proof in a civil trial, which requires the plaintiff to prove the case only by a preponderance of the evidence. This means that the evidence to support the plaintiff’s case is greater (or weightier) than the evidence that does not. It’s useful to think of the criminal standard of proof—beyond a reasonable doubt—as something like 99 percent certainty, with 1 percent doubt.Compare this to preponderance of the evidence, which we might think of as 51 percent in favor of the plaintiff’s case, but up to 49 percent doubt. This means that it is much more difficult to successfully prosecute a criminal defendant than it is to bring a successful civil claim. Since a criminal action and a civil action may be brought against a defendant for the same incident, these differences in burdens of proof can result in verdicts that seem, at first glance, to contradict each other. Perhaps the most well-known cases in recent history in which this very outcome happened were the O. J. Simpson trials. Simpson was acquitted of murder in a criminal trial, but he was found liable for wrongful death in a subsequent civil action. Check out Note 10.14 "Hyperlink: Not Guilty Might Not Mean Innocent" for a similar result in the business context.

Hyperlink: Not Guilty Might Not Mean Innocent

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601103&sid=a89tFKR4OevM

Richard Scrushy of HealthSouth was acquitted of several criminal charges relating to accounting fraud but was found civilly liable for billions. He was subsequently found guilty in a later criminal case for different crimes committed.

This extra burden reflects the fact that the defendant in a criminal case stands to lose much more than a defendant in a civil case. Even though it may seem like a very bad thing to lose one’s assets in a civil case, the loss of liberty is considered to be a more serious loss. Therefore, more protections are afforded to the criminal defendant than are afforded to defendants in a civil proceeding. Because so much is at stake in a criminal case, our due process requirements are very high for anyone who is a defendant in criminal proceedings. Due process procedures are not specifically set out by the Constitution, and they vary depending on the type of penalty that can be levied against someone. For example, in a civil case, the due process requirements might simply be notice and an opportunity to be heard. If the government intends to revoke a professional license, then the defendant might receive notice by way of a letter, and the opportunity to be heard might exist by way of written appeal. In a criminal case, however, the due process requirements are higher. This is because a criminal case carries the potential for the most serious penalties.

- 2357 reads