Investors and researchers have disputed the efficient-market hypothesis both empirically and theoretically. Behavioral economists attribute the imperfections in financial markets to a combination of cognitive biases such as overconfidence, overreaction, representative bias, information bias, and various other predictable human errors in reasoning and information processing. These have been researched by psychologists such as Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler, and Paul Slovic. These errors in reasoning lead most investors to avoid value stocks and buy growth stocks at expensive prices, which allow those who reason correctly to profit from bargains in neglected value stocks and the overreacted selling of growth stocks.

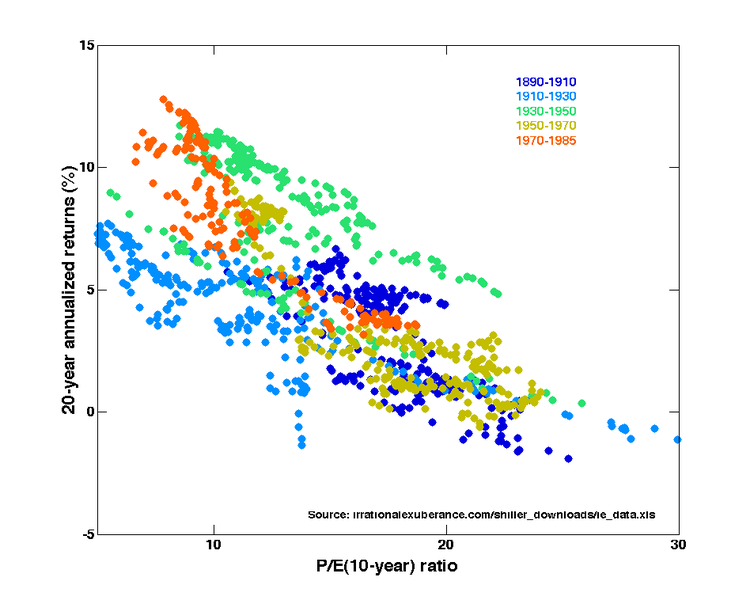

Empirical evidence has been mixed, but has generally not supported strong forms of the efficient-market hypothesis 1, 2, 3. According to Dreman and Berry, in a 1995 paper, low P/E stocks have greater returns 4. In an earlier paper Dreman also refuted the assertion by Ray Ball that these higher returns could be attributed to higher beta 5, whose research had been accepted by efficient market theorists as explaining the anomaly 6 in neat accordance with modern portfolio theory.

One can identify "losers" as stocks that have had poor returns over some number of past years. "Winners" would be those stocks that had high returns over a similar period. The main result of one such study is that losers have much higher average returns than winners over the following period of the same number of years 7. A later study showed that beta (β) cannot account for this difference in average returns 8. This tendency of returns to reverse over long horizons (i.e., losers become winners) is yet another contradiction of EMH. Losers would have to have much higher betas than winners in order to justify the return difference. The study showed that the beta difference required to save the EMH is just not there.

Speculative economic bubbles are an obvious anomaly, in that the market often appears to be driven by buyers operating on irrational exuberance, who take little notice of underlying value. These bubbles are typically followed by an overreaction of frantic selling, allowing shrewd investors to buy stocks at bargain prices. Rational investors have difficulty profiting by shorting irrational bubbles because, as John Maynard Keynes commented, "Markets can remain irrational far longer than you or I can remain solvent." Sudden market crashes as happened on Black Monday in 1987 are mysterious from the perspective of efficient markets, but allowed as a rare statistical event under the Weak-form of EMH. One could also argue that if the hypothesis is so weak, it cannot be used in statistical models due to its lack of predictive behavior.

Burton Malkiel, a well-known proponent of the general validity of EMH, has warned that certain emerging markets such as China are not empirically efficient; that the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets, unlike markets in United States, exhibit considerable serial correlation (price trends), non-random walk, and evidence of manipulation 12.

Behavioral psychology approaches to stock market trading are among some of the more promising alternatives to EMH (and some investment strategies seek to exploit exactly such inefficiencies). But Nobel Laureate co-founder of the programme—Daniel Kahneman—announced his skepticism of investors beating the market: "They're [investors] just not going to do it [beat the market]. It's just not going to happen." 13 Indeed defenders of EMH maintain that Behavioral Finance strengthens the case for EMH in that BF highlights biases in individuals and committees and not competitive markets. For example, one prominent finding in Behaviorial Finance is that individuals employ hyperbolic discounting. It is palpably true that bonds, mortgages, annuities and other similar financial instruments subject to competitive market forces do not. Any manifestation of hyperbolic discounting in the pricing of these obligations would invite arbitrage thereby quickly eliminating any vestige of individual biases. Similarly, diversification, derivative securities and other hedging strategies assuage if not eliminate potential mispricings from the severe risk-intolerance (loss aversion) of individuals underscored by behavioral finance. On the other hand, economists, behaviorial psychologists and mutual fund managers are drawn from the human population and are therefore subject to the biases that behavioralists showcase. By contrast, the price signals in markets are far less subject to individual biases highlighted by the Behavioral Finance programme. Richard Thaler has started a fund based on his research on cognitive biases. In a 2008 report he identified complexity and herd behavior as central to the global financial crisis of 2008 14.

Further empirical work has highlighted the impact transaction costs have on the concept of market efficiency, with much evidence suggesting that any anomalies pertaining to market inefficiencies are the result of a cost benefit analysis made by those willing to incur the cost of acquiring the valuable information in order to trade on it. Additionally the concept of liquidity is a critical component to capturing "inefficiencies" in tests for abnormal returns. Any test of this proposition faces the joint hypothesis problem, where it is impossible to ever test for market efficiency, since to do so requires the use of a measuring stick against which abnormal returns are compared - one cannot know if the market is efficient if one does not know if a model correctly stipulates the required rate of return. Consequently, a situation arises where either the asset pricing model is incorrect or the market is inefficient, but one has no way of knowing which is the case.

A key work on random walk was done in the late 1980s by Profs. Andrew Lo and Craig MacKinlay; they effectively argue that a random walk does not exist, nor ever has 15. Their paper took almost two years to be accepted by academia and in 1999 they published "A Non-random Walk Down Wall St." which collects their research papers on the topic up to that time.

Economists Matthew Bishop and Michael Green claim that full acceptance of the hypothesis goes against the thinking of Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes, who both believed irrational behavior had a real impact on the markets 16.

Warren Buffett has also argued against EMH, saying the preponderance of value investors among the world's best money managers rebuts the claim of EMH proponents that luck is the reason some investors appear more successful than others 17. As Malkiel 18 has shown, over the 30 years (to 1996) more than two-thirds of professional portfolio managers have been outperformed by the S&P 500 Index (and, more to the point, there is little correlation between those who outperform in one year and those who outperform in the next.

- 5687 reads