Every morning, people leave small country towns in cars to go their workplace and are passed by others whose work destination is the place they have just left. In this dynamic transport shuttle everyone is somehow connected with, and supporting, a transport system based on private cars. Science now indicates that this massive carbon economy has dislodged the biosphere from one of its stable states that has supported human evolution for the past two million years. Climatic change has started to unfold and the world is not a unified community with powers to produce a global technological fix. Many are beginning to believe that in this scenario, sustainable development, with its adherence to annual year on year increases in spending power, is pointing in the wrong direction. Rather, what is needed is a sustainable economic retreat. This will require global strategies to adjust the relationship between production systems and natural resources to generate rates of waste emission that the biosphere can assimilate.

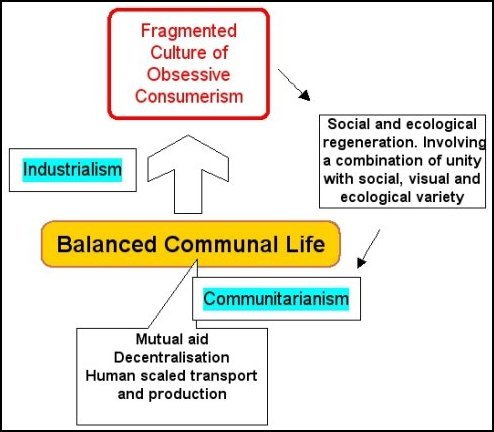

In contrast, a market town in the 1850s was a small balanced community. It represented the oldest kind of human institution, found absolutely everywhere throughout the world in all kinds of societies. Since the late Palaeolithic more than 100 billion human beings have lived on earth and the majority have spent their entire life as members of very small groups, rarely of more than a few hundred persons. Their production systems were each composed of few people. This picture is the staring point for ideas that there is a basic human need for small communities, which is encoded in our genes. It is in our behavioural makeup that we still orientate towards a group; the small group of the village and the tribe. Rural communities in the British 2001 Population Census are still small, yet market towns with their surrounding villages now lack any sense of communal focus or scale of production. Their fragmented residential, commercial and cultural centres emphasise transportation by car so that the inhabitants also lack any sense of pedestrian scale. Village and town are no longer serving as magnets for both people and ideas. People now seem to like isolation. New housing infills are socially sterile. Everything is new clean and neat. Neighbours are usually only glimpsed as they walk to the car. Each house is a small fortress equipped with a barking dog or alarm system. The only visible activity is macho man cutting his lawns. There are obviously great differences between old and new. Leaving aside the crushing poverty, we can legitimately ask if a pre-industrial community was really a haven of creativity and neighbourly harmony, which could serve as a planning model for today’s social ills. Have we really lost a unique combination of unity with social, visual and ecological variety? Is there an historical small-town target that modern planners should use for social and ecological regeneration? Planners, since their profession emerged in the late 19th century, have thought so. Nineteenth century society was based on ideas of mutual aid, political and economic decentralisation, human-scaled production and communitarian ideas (Fig 11.2).

These ideas of social ecology, as a recipe for human life, were first articulated at the end of the 19th century for an improved cooperative economy by the Russian geographer Peter Kropokin. The Scottish planner, Patrick Geddes and his pupil Lewis Mumford developed them in Britain. Americans have followed this path since the 1990s to restore the integrity of their basic institutions and turn back disturbing trends toward crime, social disorder, and family breakdown. The past decade has been an era of important social reforms: in the schools, in the criminal justice system, in family policy. In states and localities across the U.S.A, citizens have fought for greater emphasis on character, individual responsibility, and virtues and values in the public square. Partly as a result, on a host of "leading social indicators”, such as rates of violent crime, rates of youth crime, levels of teenage pregnancy, and even student test scores, the nation is showing incremental but significant improvements.

Communitarian ideas and policy approaches have been playing a major role in this growing North American movement of cultural and institutional regeneration. Communitarian thinkers are in the forefront of the ‘Character Education Movement’, which is fostering a return to the teaching of good personal conduct and individual responsibility in thousands of schools around the country. Likewise, communitarians have been playing a role in the new community-based approaches to criminal justice, which are showing solid success in restoring neighbourhood order and achieving real reductions in violent crime. In the area of family policy, communitarians have worked for policies to strengthen families and discourage divorce. They have led in devising fresh, incentive-based policies designed to discourage a casual approach to marriage and to promote "children-first" thinking and family stability, while at the same time preserving the rights of women and men. The need for action has now reached the large politically influential community of the Evangelical Church, where a group of leaders, convinced of the science behind climate change, is trying to persuade its local membership to reduce their domestic carbon emissions. Communitarianism has become a part of one of the most innovative movements working to renew and revitalize American society.

Yesterday in every town is now a piece of the history of this movement, and everyone who lived through the past twenty-four hours holds some of the public evidence that could be put towards learning about the past to better understand the present and shape the future. The history of communities is in the making; it is not a dead thing to be pulled out and praised or deplored; it is the inhabitants who are custodians of the past, by the recording of the present. To make history part of the community’s social toolkit there has to be a reorientation of history towards ecology. Social ecology is nothing more than an environmentally orientated study of a community, which explores a timeline of the relations between ecological infrastructure, politics, community organisations, the economy and culture. The creation of small town models is therefore an important practical aim for the enrichment of cultural ecology as an educational resource.

- 2407 reads