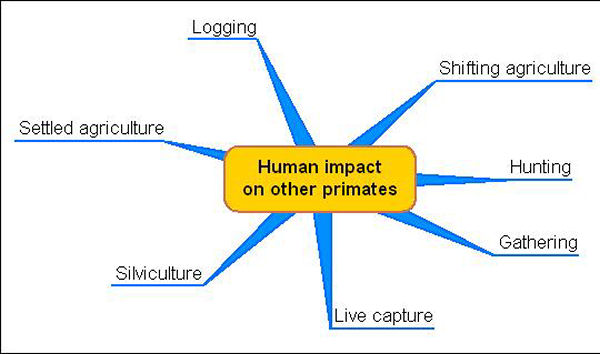

The human impact of people on forest primates ranges from the outright destruction of their arboreal habitat, through felling or damming river systems, to the isolation of small populations in isolated pockets of forest, which are below the threshold required to maintain a viable population. Apart from logging and clearance for agriculture, other impacts are removal of primates as agricultural pests, as food for human or pet consumption, as bait, and the taking of live animals as pets or for laboratory research.

In most parts of the primate habitat of Asia, habitat disturbance commonly takes the form of commercial logging as well as shifting cultivation. The effects of logging on primate survival are tied to the type of logging practices and the requirements of the animals. One key factor in survival is whether or not timber sought by loggers is also their food resource. In this respect it has been shown that Malaysian primates in a given area can survive the destruction of up to half of the forest. Also, high densities of some primates can be reached in surviving ‘islands’ in a ‘sea’ of monocultures. These situations only apply to a limited number of species.

Hunting of primates is not as great a problem in Asia as in Africa or South America because three of the major religions there (Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism) have proscriptions against eating primates. Nonetheless, hunting by aboriginal groups is common in Indonesia, and Chinese hunt all species of monkeys in China and in other Asian countries in which they live. In Asia, the major direct threat to primates is that they are traded commercially. The commercial use of wild monkeys for biomedical research is responsible for the decline in macaques, an Asian genus.

Although non-timber products provide a justification for the conservation of forest, if the markets for them are successfully developed, the result could be overexploitation, leading to clear-cutting for areas of commercial cultivation. Understory clearing, often for fodder for domestic animals or for plantations of shade-loving crops, destroys seedlings, and with them, the possibility of the regeneration of canopy trees.

Shifting cultivation increases the proportion of secondary forest at the expense of primary forest. In Asia, this change favors cercopithecines at the expense of colobines. In peninsular Malaysia, the primate biomass in primary forest is dominated by colobines (Presbytis spp.), whereas secondary forest, riverine swamp, domestic orchards, paddy fields, and so forth commonly host cercopithecines, particularly long-tailed macaques. For open-country monkey species like most macaques (Macaca spp.) and the Hanuman langur (Presbytis entellus), any kind of disturbance that results in landscapes such as the meadow like communities created by clear-cutting, grazing, and crop planting mimics the forest edge or savanna to which they originally were adapted. It has been argued that the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatto), which prefers feeding on ground herbs that occur in disturbed sites, has spread with the disappearance of the forests of Asia during the Pleistocene glaciations and that continues to prosper in the face of the human colonization of forestlands.

Despite the Indo-Pacific’s unsurpassed biological richness, many species other than primates are in immediate danger of extinction. The number of current extinctions globally and regionally, in fact, rivals that of the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. Given the increasing scale and scope of current threats such as logging, agricultural expansion, and increasing demographic pressures on natural resources, new conservation strategies and fieldwork with local governments and communities are clearly necessary if biodiversity in the Indo-Pacific is to be protected.

- 3537 reads