LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to understand and articulate answers to the following questions:

- What are the basic building blocks of organizational structure?

- What types of structures exist, and what are advantages and disadvantages of each?

- What is control and why is it important?

- What are the different forms of control and when should they be used?

- What are the key legal forms of business, and what implications does the choice of a business form have for organizational structure?

Can Oil Well Services Fuel Success for GE?

In February 2011, General Electric (GE) reached an agreement to acquire the well-support division of John Wood Group PLC for $2.8 billion. This was GE’s third acquisition of a company that provides services to oil wells in only five months. In October 2010, GE added the deepwater exploration capabilities of Wellstream Holdings PLC for $1.3 billion. In December 2010, part and equipment maker Dresser was acquired for $3 billion. By spending more than $7 billion on these acquisitions, GE executives made it clear that they had big plans within the oil well services business.

While many executives would struggle to integrate three new companies into their firms, experts expected GE’s leaders to smoothly execute the transitions. In describing the acquisition of John Wood Group PLC, for example, one Wall Street analyst noted, “This is a nice bolt-on deal for GE.” 1 In other words, this analyst believed that John Wood Group PLC could be seamlessly added to GE’s corporate empire. The way that GE was organized fueled this belief.

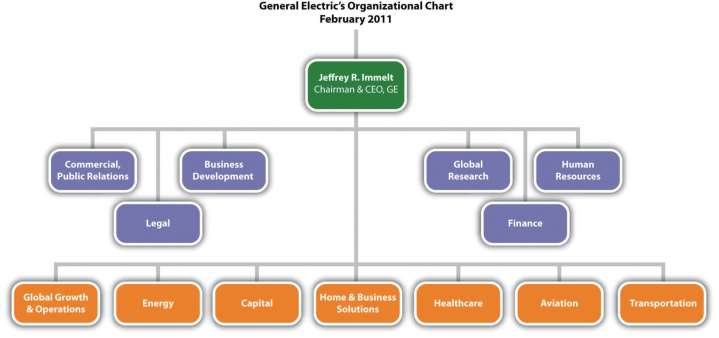

GE’s organizational structure includes six divisions, each devoted to specific product categories: (1) Energy (the most profitable division), (2) Capital (the largest division), (3) Home & Business Solutions,(4) Healthcare, (5) Aviation, and (6) Transportation. Within the Energy division, there are three subdivisions: (1) Oil & Gas, (2) Power & Water, and (3) Energy Services. Rather than having the entire organization involved with integrating John Wood Group PLC, Wellstream Holdings PLC, and Dresser into GE, these three newly acquired companies would simply be added to the Oil & Gas subdivisions within the Energy division.

In addition to the six product divisions, GE also had a division devoted to Global Growth & Operations. This division was responsible for all sales of GE products and services outside the United States. The

Global Growth & Operations division was very important to GE’s future. Indeed, GE’s CEO Jeffrey Immelt expected that countries other than the United States will account for 60 percent of GE’s sales in the future, up from 53 percent in 2010. To maximize GE’s ability to respond to local needs, the Global Growth& Operations was further divided into twelve geographic regions: China, India, Southeast Asia, Latin/South America, Russia, Canada, Australia, the Middle East, Africa, Germany, Europe, and Japan. 2

Finally, like many large companies, GE also provided some centralized services to support all its units. These support areas included public relations, business development, legal, global research, human resources, and finance. By having entire units of the organization devoted to these functional areas, GE hoped not only to minimize expenses but also to create consistency across divisions.

Growing concerns about the environmental effects of drilling, for example, made it likely that GE’s oil well services operations would need the help of GE’s public relations and legal departments in the future. Other important questions about GE’s acquisitions remained open as well. In particular, would the organizational cultures of John Wood Group PLC, Wellstream Holdings PLC, and Dresser mesh with the culture of GE? Most acquisitions in the business world fail to deliver the results that executives expect, and the incompatibility of organizational cultures is one reason why.

The word executing used in this chapter’s title has two distinct meanings. These meanings

were cleverly intertwined in a quip by John McKay. McKay had the misfortune to be the head coach of a hapless professional football team. In one game, McKay’s offensive unit played

particularly poorly. When McKay was asked after the game what he thought of his offensive unit’s execution, he wryly responded, “I am in favor of it.”

In the context of business, execution refers to how well a firm

such as GE implements the strategies that executives create for it. This involves the creation and operation of both an appropriate organizational structure and an appropriate organizational

control processes. Executives who skillfully orchestrate structure and control are likely to lead their firms to greater levels of success. In contrast, those executives who fail to do so are

likely to be viewed by stakeholders such as employees and owners in much the same way Coach McKay viewed his offense: as worthy of execution.

- 5606 reads