The purpose of rent control is to make rental units cheaper for tenants than they would otherwise be. Unlike agricultural price controls, rent control in the United States has been largely a local phenomenon, although there were national rent controls in effect during World War II. Currently, about 200 cities and counties have some type of rent control provisions, and about 10% of rental units in the United States are now subject to price controls. New York City’s rent control program, which began in 1943, is among the oldest in the country. Many other cities in the United States adopted some form of rent control in the 1970s. Rent controls have been pervasive in Europe since World War I, and many large cities in poorer countries have also adopted rent controls.

Rent controls in different cities differ in terms of their flexibility. Some cities allow rent increases for specified reasons, such as to make improvements in apartments or to allow rents to keep pace with price increases elsewhere in the economy. Often, rental housing constructed after the imposition of the rent control ordinances is exempted. Apartments that are vacated may also be decontrolled. For simplicity, the model presented here assumes that apartment rents are controlled at a price that does not change.

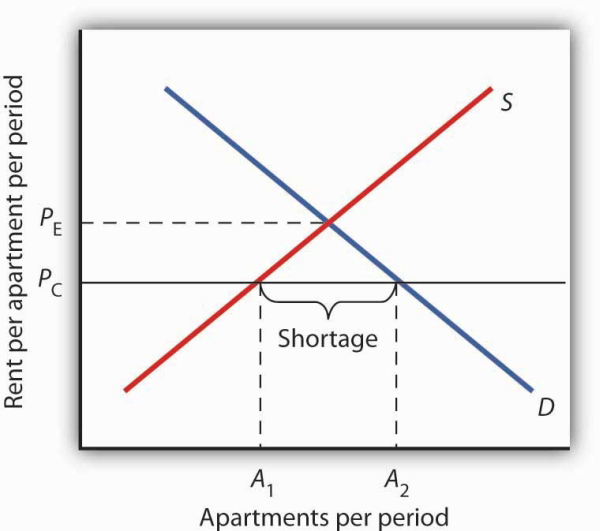

A price ceiling on apartment rents that is set below the equilibrium rent creates a shortage of apartments equal to (A2 − A1) apartments.

Figure 4.8shows the market for rental apartments. Notice that the demand and supply curves are drawn to look like all the other demand and supply curves you have encountered so far in this text: the demand curve is downward-sloping and the supply curve is upward-sloping.

The demand curve shows that a higher price (rent) reduces the quantity of apartments demanded. For example, with higher rents, more young people will choose to live at home with their parents. With lower rents, more will choose to live in apartments. Higher rents may encourage more apartment sharing; lower rents would induce more people to live alone.

The supply curve is drawn to show that as rent increases, property owners will be encouraged to offer more apartments to rent. Even though an aerial photograph of a city would show apartments to be fixed at a point in time, owners of those properties will decide how many to rent depending on the amount of rent they anticipate. Higher rents may also induce some homeowners to rent out apartment space. In addition, renting out apartments implies a certain level of service to renters, so that low rents may lead some property owners to keep some apartments vacant.

Rent control is an example of a price ceiling, a maximum allowable price. With a price ceiling, the government forbids a price above the maximum. A price ceiling that is set below the equilibrium price creates a shortage that will persist.

Suppose the government sets the price of an apartment at PC in Figure 4.8. Notice that PC is below the equilibrium price of PE. At PC, we read over to the supply curve to find that sellers are willing to offer A1 apartments. Reading over to the demand curve, we find that consumers would like to rent A2 apartments at the price ceiling of PC. Because PC is below the equilibrium price, there is a shortage of apartments equal to (A2-A1). (Notice that if the price ceiling were set above the equilibrium price it would have no effect on the market since the law would not prohibit the price from settling at an equilibrium price that is lower than the price ceiling.)

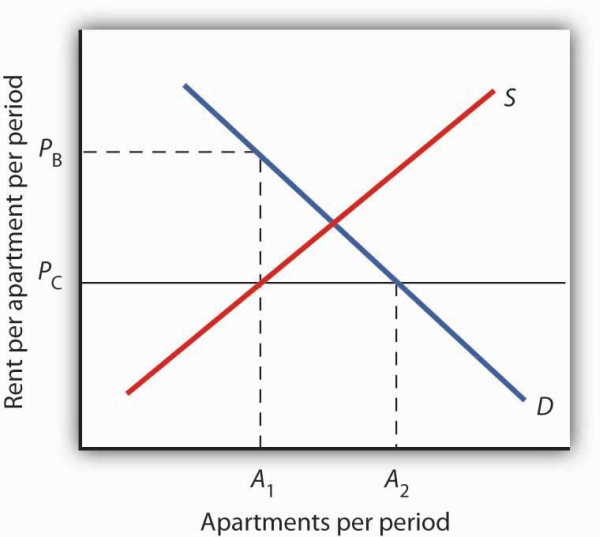

Controlling apartment rents at PC creates a shortage of (A2 − A1) apartments. For A1apartments, consumers are willing and able to pay PB, which leads to various “backdoor” payments to apartment owners.

If rent control creates a shortage of apartments, why do some citizens nonetheless clamor for rent control and why do governments often give in to the demands? The reason generally given for rent control is to keep apartments affordable for low-and middle-income tenants.

But the reduced quantity of apartments supplied must be rationed in some way, since, at the price ceiling, the quantity demanded would exceed the quantity supplied. Current occupants may be reluctant to leave their dwellings because finding other apartments will be difficult. As apartments do become available, there will be a line of potential renters waiting to fill them, any of whom is willing to pay the controlled price of PC or more. In fact, reading up to the demand curve in Figure 4.9from A1 apartments, the quantity available at PC, you can see that for A1 apartments, there are potential renters willing and able to pay PB. This often leads to various “backdoor” payments to apartment owners, such as large security deposits, payments for things renters may not want (such as furniture), so-called “key” payments (“The monthly rent is $500 and the key price is $3,000”), or simple bribes.

In the end, rent controls and other price ceilings often end up hurting some of the people they are intended to help. Many people will have trouble finding apartments to rent. Ironically, some of those who do find apartments may actually end up paying more than they would have paid in the absence of rent control. And many of the people that the rent controls do help (primarily current occupants, regardless of their income, and those lucky enough to find apartments) are not those they are intended to help (the poor). There are also costs in government administration and enforcement.

Because New York City has the longest history of rent controls of any city in the United States, its program has been widely studied. There is general agreement that the rent control program has reduced tenant mobility, led to a substantial gap between rents on controlled and uncontrolled units, and favored long-term residents at the expense of newcomers to the city. Richard Arnott, “Time for Revisionism on Rent Control,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(1) (Winter, 1995): 99–120. These distortions have grown over time, another frequent consequence of price controls.

A more direct means of helping poor tenants, one that would avoid interfering with the functioning of the market, would be to subsidize their incomes. As with price floors, interfering with the market mechanism may solve one problem, but it creates many others at the same time.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Price floors create surpluses by fixing the price above the equilibrium price. At the price set by the floor, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded.

- In agriculture, price floors have created persistent surpluses of a wide range of agricultural commodities. Governments typically purchase the amount of the surplus or impose production restrictions in an attempt to reduce the surplus.

- Price ceilings create shortages by setting the price below the equilibrium. At the ceiling price, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied.

- Rent controls are an example of a price ceiling, and thus they create shortages of rental housing.

- It is sometimes the case that rent controls create “backdoor” arrangements, ranging from requirements that tenants rent items that they do not want to outright bribes, that result in rents higher than would exist in the absence of the ceiling.

TRY IT!

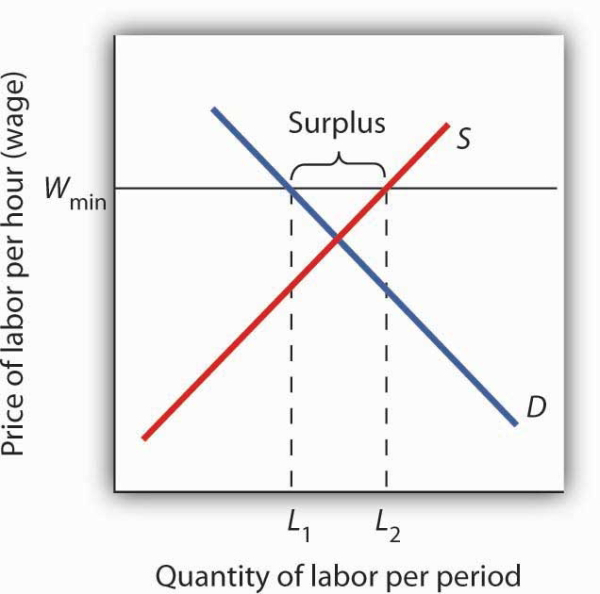

A minimum wage law is another example of a price floor. Draw demand and supply curves for unskilled labor. The horizontal axis will show the quantity of unskilled labor per period and the vertical axis will show the hourly wage rate for unskilled workers, which is the price of unskilled labor. Show and explain the effect of a minimum wage that is above the equilibrium wage.

Case in Point: Corn: It Is Not Just Food Any More

Government support for corn dates back to the Agricultural Act of 1938 and, in one form or another, has been part of agricultural legislation ever since. Types of supports have ranged from government purchases of surpluses to target pricing, land set asides, and loan guarantees. According to one estimate, the U.S. government spent nearly $42 billion to support corn between 1995 and 2004.

Then, during the period of rising oil prices of the late 1970s and mounting concerns about dependence on foreign oil from volatile regions in the world, support for corn, not as a food, but rather as an input into the production of ethanol—an alternative to oil-based fuel—began. Ethanol tax credits were part of the Energy Act of 1978. Since 1980, a tariff of 50¢ per gallon against imported ethanol, even higher today, has served to protect domestic corn-based ethanol from imported ethanol, in particular from sugarcane-based ethanol from Brazil.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 was another milestone in ethanol legislation. Through loan guarantees, support for research and development, and tax credits, it mandated that 4 billion gallons of ethanol be used by 2006 and 7.5 billion gallons by 2012. Ethanol production had already reached 6.5 billion gallons by 2007, so new legislation in 2007 upped the ante to 15 billion gallons by 2015.

Beyond the increased amount the government is spending to support corn and corn-based ethanol, criticism of the policy has three major prongs:

- Corn-based ethanol does little to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil because the energy required to produce a gallon of corn-based ethanol is quite high. A 2006 National Academy of Sciences paper estimated that one gallon of ethanol is needed to bring 1.25 gallons of it to market. Other studies show an even less favorable ratio.

- Biofuels, such as corn-based ethanol, are having detrimental effects on the environment, with increased deforestation, stemming from more land being used to grow fuel inputs, contributing to global warming.

- The diversion of corn and other crops from food to fuel is contributing to rising food prices and an increase in world hunger. C. Ford Runge and Benjamin Senauer wrote in Foreign Affairsthat even small increases in prices of food staples have severe consequences on the very poor of the world, and “Filling the 25-gallon tank of an SUV with pure ethanol requires over 450 pounds of corn—which contains enough calories to feed one person for a year.”

Some of these criticisms may be contested as exaggerated: Will the ratio of energy-in to energy-out improve as new technologies emerge for producing ethanol? Did not other factors, such as weather and rising food demand worldwide, contribute to higher grain prices? Nonetheless, it is clear that corn-based ethanol is no free lunch. It is also clear that the end of government support for corn is nowhere to be seen.

Sources: Alexei Barrionuevo, “Mountains of Corn and a Sea of Farm Subsidies,” New York Times, November 9, 2005, online version; David Freddoso, “Children of the Corn,” National Review Online, May 6, 2008; C. Ford Runge and Benjamin Senauer, “How Biofuels Could Starve the Poor,”Foreign Affairs, May/June 2007, online version; Michael Grunwald, “The Clean Energy Scam,”Time171:14 (April 7, 2008): 40–45.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

A minimum wage (Wmin) that is set above the equilibrium wage would create a surplus of unskilled labor equal to (L2-L1). That is, L2 units of unskilled labor are offered at the minimum wage, but companies only want to use L1 units at that wage. Because unskilled workers are a substitute for a skilled workers, forcing the price of unskilled workers higher would increase the demand for skilled labor and thus increase their wages.

- 瀏覽次數:4989