Federal efforts to control air and water pollution in the United States have produced mixed results. Air quality has generally improved; water quality has improved in some respects but deteriorated in others.

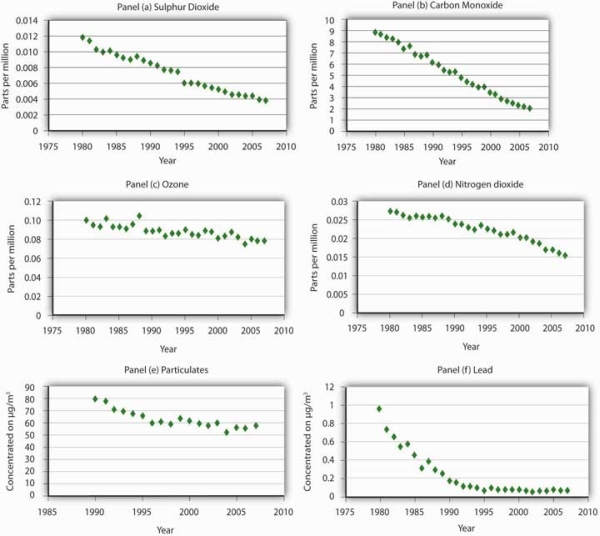

Figure 18.5shows how annual average concentrations of airborne pollutants in major U.S. cities have declined since 1975. Lead concentrations have dropped most dramatically, largely because of the increased use of unleaded gasoline.

The average concentration of major air pollutants in U.S. cities has declined since 1975.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2006 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2006), Table 359, p. 228. Observations before 1999 are taken from previous volumes of the abstract; supplemented by National Air Quality and Emissions Trends Report, 2003, Table A-1b (Environmental Protection Agency, 2005).

Public policy has generally stressed command-and-control approaches to air and water pollution. To reduce air pollution, the EPA sets air quality standards that regions must achieve, then tells polluters what adjustments they must make in order to meet the standards. For water pollution, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set emissions limits based on the technologies it considers reasonable to require of polluters. If the implementation of a particular technology will reduce a polluter’s emissions by 20%, for example, the EPA will require a 20% reduction in emissions. National standards have been imposed; no effort has been made to consider the benefits and costs of pollution in individual streams. Further, the EPA’s technology-based approach pays little attention to actual water quality—and has produced few gains.

Moreover, environmental problems go beyond national borders. For example, sulfur dioxide emitted from plants in the United States can result in acid rain in Canada and elsewhere. Another possible pollution problem that extends across national borders is suggested by the global warming hypothesis.

Many scientists have argued that increasing emissions of greenhouse gases, caused partly by the burning of fossil fuels, trap ever more of the sun’s energy and make the planet warmer. Global warming, they argue, could lead to flooding of coastal areas, losses in agricultural production, and the elimination of many species. If this global warming hypothesis is correct, then carbon dioxide is a pollutant with global implications, one that calls for a global solution.

At the 1997 United Nations conference in Kyoto, Japan, the industrialized countries agreed to cuts in carbon dioxide emissions of 5.2% below the 1990 level by 2010. At the 1998 conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 170 countries agreed on a two-year action plan for designing mechanisms to reduce emissions and procedures to encourage transfers of new energy technologies to developing countries.

While the delegates to the conferences sign the various protocols, countries are not bound by them until ratified by appropriate governmental bodies. By 2005, the vast majority of the world’s nations had ratified the agreement. The United States had neither signed nor ratified the agreement.

Debates at these conferences have been over the extent to which developing countries should be required to reduce their emissions and over the role that market mechanisms should play. Developing countries argue that their share in total emissions is fairly small and that it is unfair to ask them to give up economic growth, given their lower income levels. As for how emissions reductions will be achieved, the United States has been the strongest advocate for emissions trading in which each country would receive a certain number of tradable emissions rights. This provision has been incorporated in the agreement.

That market approaches have entered the national and international debates on dealing with environmental issues, and to a large extent have even been used, demonstrates the power of economic analysis. Economists have long argued that as pollution-control authorities replace command-and-control strategies with incentive approaches, society will reap huge savings. The economic argument has rested on acknowledging the opportunity costs of addressing environmental concerns and thus has advocated policies that achieve improvements in the environment in the least costly ways.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Public sector intervention is generally needed to move the economy toward the efficient solution in pollution problems.

- Command-and-control approaches are the most widely used methods of public sector intervention, but they are inefficient.

- The exchange of pollution rights can achieve a given reduction in emissions at the lowest cost possible. It also creates incentives to reduce pollution demand through technological change.

- Tax policy can also achieve a least-cost reduction in emissions.

TRY IT!

Based on your answer to the previous Try It! problem, a tax of what amount would result in the efficient quantity of pollution?

Case in Point: Road Pricing in Singapore

The urban highways of virtually every city in the world are heavily congested in what is fancifully referred to as the “rush hour.” Traffic during this period hardly rushes. The problem of traffic congestion is analogous to the problem of pollution, and it lends itself to the same solution.

Suppose that you are driving into any major city on a weekday at eight o’clock in the morning. The highway is congested when you drive onto it. Your car adds to that congestion. You, of course, experience the average level of congestion. But, your car slows every car behind you on the highway by a small amount. Multiplying that extra slowing by the number of cars behind you gives the marginal delay of adding your own car to an already congested highway. That marginal cost is many times greater than the average cost that you actually face. The result is an inefficient solution in which roads are congested far beyond the point that would be economically efficient. The late William Vickrey, who won the Nobel Prize for his work in the economics of public finance, advocated a system of road pricing that would put an end to congested highways.

Mr. Vickrey’s dream is a reality in Singapore. The island-nation’s 700,000 cars are each required to subscribe to the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) system and to have an ERP card on their windshield. Further, each driver is required to maintain a deposit of electronic cash in the card. Tolls are charged during rush hour for the highways leading into the downtown area. There is also a charge for using downtown streets. Tolls range from $0.50 to $1.00 and are only levied if the road threatens to become congested. Using highways and streets is free at other times. ERP managers adjust the tolls to avoid “jam-ups,” as they are called in Singapore. Managers attempt to keep traffic flowing at 30 to 40 mph on the highways and 15 to 20 mph on downtown streets.

When a car passes an electronic gurney, it automatically takes the charge out of the ERP card on the windshield. When a charge is taken from the card, the driver hears a beep. If the card balance falls below $5, several beeps are heard. The cards can be placed in ATMs to put additional funds in them. A car that does not have enough money in its card is photographed and the owner of the car receives a $45 citation in the mail. The tolls keep casual drivers off the roads during rush hour. Commuters generally find it cheaper to use the island’s excellent rapid transit system.

The system is not universally popular. People in Singapore refer to the system as “Eternally Raising Prices.” The manager of the system, Hiok Seng Tan, rejects the criticism. “It’s not just a system to get more money of Singaporeans,” he told the Boston Globe. In fact, the system takes in only $44 million per year; the money is used to maintain the system.

Singapore’s system is an example of a price system to manage what is, in effect, a pollution problem. It appears to be effective. Jam-ups are uncommon. Would such a system work in other areas? The idea is not politically popular. Gregory B. Christainsen, a professor of economics at California State University at East Bay, notes that Singapore is dominated by a single party and questions whether other urban areas are ready for the approach. Still, the system works and the concept is one more urban areas should consider.

Sources: Alex Beam, “Where Traffic Has Been Tamed,” Boston Globe, (May 2, 2004): M-7; Gregory B. Christainsen, “Road Pricing in Singapore after 30 Years,” Cato Journal, 26(1) (Winter 2006): 71–88.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

The paper mill will reduce its pollution until the marginal benefit of polluting equals the tax. In this case a tax of $70 would cause the paper mill to reduce its pollution to 4 tons, the efficient level. At pollution levels below that amount, the marginal benefit of polluting exceeds the tax, and so the paper mill is better off polluting and paying the tax. At pollution levels greater than that amount, the marginal benefit of polluting is less than the tax.

- 3209 reads