Another justification for protectionist measures is that free trade is unfair if it pits domestic firms against foreign rivals who do not have to adhere to the same regulatory standards. In the debate over NAFTA, for example, critics warned that Mexican firms, facing relatively lax pollution control standards, would have an unfair advantage over

U.S. firms if restraints on trade between the two countries were removed.

Economic theory suggests, however, that differences in pollution-control policies can be an important source of comparative advantage. In general, the demand for environmental quality is positively related to income. People in higher-income countries demand higher environmental quality than do people in lower-income countries. That means that pollution has a lower cost in poorer than in richer countries. If an industry generates a great deal of pollution, it may be more efficient to locate it in a poor country than in a rich country. In effect, a poor country’s lower demand for environmental quality gives it a comparative advantage in production of goods that generate a great deal of pollution.

Provided the benefits of pollution exceed the costs in the poor country, with the costs computed based on the preferences and incomes of people in that country, it makes sense for more of the good to be produced in the poor country and less in the rich country. Such an allocation leaves people in both countries better off than they would be otherwise. Then, as freer trade leads to higher incomes in the poorer countries, people there will also demand improvements in environmental quality.

Do economists support any restriction on free international trade? Nearly all economists would say no. The gains from trade are so large, and the cost of restraining it so high, that it is hard to find any satisfactory reason to limit trade.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Protectionist measures seek to limit the quantities of goods and services imported from foreign countries. They shift the supply curve for each of the goods or services protected to the left.

- The primary means of protection are tariffs and quotas.

- Antidumping proceedings have emerged as a common means of protection.

- Voluntary export restrictions are another means of protection; they are rarely voluntary.

- Other protectionist measures can include safety standards, restrictions on environmental quality, labeling requirements, and quality standards.

- Protectionist measures are sometimes justified using the infant industry argument, strategic trade policy, job protection, “cheap” foreign labor and outsourcing, national security, and differences in environmental standards.

TRY IT!

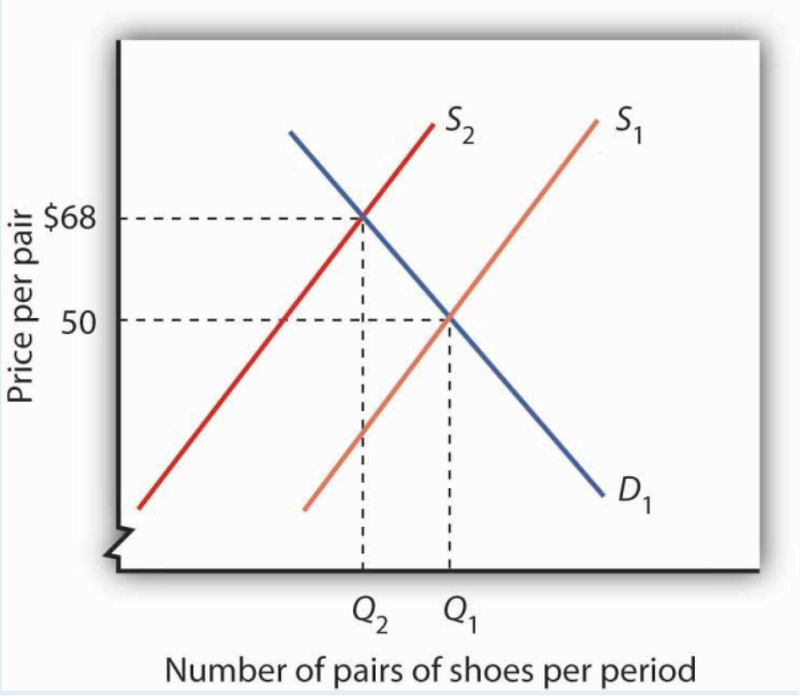

Suppose the United States imposes a quota reducing its imports of shoes by one-half (roughly 85–90% of the shoes now sold in the United States are imported). Assume that shoes are produced under conditions of perfect competition and that the equilibrium price of shoes is now $50 per pair. Illustrate and explain how this quota will affect the price and output of shoes in the United States.

Case in Point: Outsourcing and Employment

The phenomenon of outsourcing has become common as the Internet and other innovations in communication have made it easier for firms to transfer aspects of their production overseas. At the same time, countries such as India and China have invested heavily in education and have produced a sizable workforce of professional people capable of filling relatively high level positions for firms in more developed countries.

The very idea of outsourcing rankles politicians on the left and on the right. In the United States, there have been numerous congressional hearings on outsourcing and proposals to block firms that engage in the practice from getting government contracts.

By outsourcing, firms are able to reduce their production costs. As we have seen, a reduction in production costs translates into increased output and falling prices. From a consumer’s point of view, then, outsourcing should be a very good thing. The worry many commentators express, however, is that outsourcing will decimate employment in the United States, particularly among high-level professionals. Matthew J. Slaughter, an economist at Dartmouth University, examined employment trends from 1991 to 2001 among multinational U.S. firms that had outsourced jobs. Those firms outsourced 2.8 million jobs during the period.

Were the 2.8 million jobs simply lost? Mr. Slaughter points out that there are three reasons to expect that the firms that reduced production costs by outsourcing would actually increase their domestic employment. First, by lowering cost, firms are likely to expand the quantity they produce. The foreign workers who were hired, who Mr. Slaughter refers to as “affiliate workers,” appeared to be complements to American workers rather than substitutes. If they are complements rather than substitutes, then outsourcing could lead to increased employment in the country that does the outsourcing.

A second reason outsourcing could increase employment is that by lowering production cost, firms that increase the scale of their operations through outsourcing need more domestic workers to sell the increased output, to coordinate its distribution, and to develop the infrastructure to handle all those goods.

Finally, firms that engage in outsourcing are also likely to increase the scope of their operations. They will need to hire additional people to explore other product development, to engage in research, and to seek out new markets for the firm’s output.

Thus, Mr. Slaughter argues that outsourcing may lead to increased employment because domestic workers are complements to foreign workers, because outsourcing expands the scale of a firm’s operations, and because it expands the scope of operations. What did the evidence show? Remember the 2.8 million jobs that multinational firms based in the United States outsourced between 1991 and 2001? Employment at those same U.S. firms increased by 5.5 million jobs during the period. Thus, with the phenomena of complementarity, increases in scale, and increases of scope, each job outsourced led to almost two additional jobs in the United States.

The experience of two quite dissimilar firms illustrates the phenomenon. Wal-Mart began expanding its operations internationally in about 1990. Today, it manages its global operations from its headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas where it employs 15,000 people. Roughly 1,500 of these people coordinate the flow of goods among WalMart’s stores throughout the world. Those 1,500 jobs would not exist were it not for globalization. Xilinx, the high technology research and development firm, generates sales of about $1.5 billion per year. Sixty-five percent of its sales are generated outside the United States. But 80% of its employees are in the United States.

Outsourcing, then, generates jobs. It does not destroy them. Mr. Slaughter concludes: “Instead of lamenting ongoing foreign expansion of U.S. multinationals, if history is our guide then we should be encouraging it.”

Source: Matthew J. Slaughter, “Globalization and Employment by U.S. Multinationals: A Framework and Facts,” Daily Tax Report (March 26, 2004): 1–12.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

The quota shifts the supply curve to the left, increasing the price of shoes in the United States and reducing the equilibrium quantity. In the case shown, the price rises to $68. Because you are not given the precise positions of the demand and supply curves, you can only conclude that price rises; your graph may suggest a different price. The important thing is that the new price is greater than $50.

- 2944 reads