We turn finally to the case of land that is used solely for the space it affords for other activities—parks, buildings, golf courses, and so forth. We shall assume that the carrying capacity of such land equals its quantity.

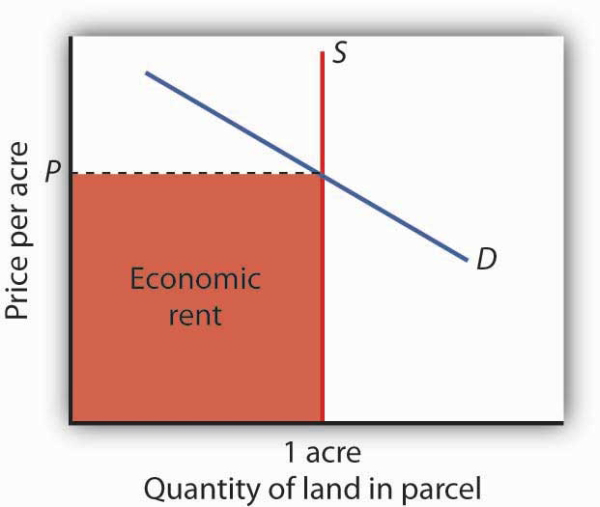

The price of a one-acre parcel of land is determined by the intersection of a vertical supply curve and the demand curve for the parcel. The sum paid for the parcel, shown by the shaded area, is economic rent.

The supply of land is a vertical line. The quantity of land in a particular location is fixed. Suppose, for example, that the price of a one-acre parcel of land is zero. At a price of zero, there is still one acre of land; quantity is unaffected by price. If the price were to rise, there would still be only one acre in the parcel. That means that the price of the parcel exceeds the minimum price—zero—at which the land would be available. The amount by which any price exceeds the minimum price necessary to make a resource available is called economic rent.

The concept of economic rent can be applied to any factor of production that is in fixed supply above a certain price. In this sense, much of the salary received by Brad Pitt constitutes economic rent. At a low enough salary, he might choose to leave the entertainment industry. How low would depend on what he could earn in a best alternative occupation. If he earns $30 million per year now but could earn $100,000 in a best alternative occupation, then $29.9 million of his salary is economic rent. Most of his current earnings are in the form of economic rent, because his salary substantially exceeds the minimum price necessary to keep him supplying his resources to current purposes.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Natural resources are either exhaustible or renewable.

- The demand for the services of a natural resource in any period is given by the marginal revenue product of those services.

- Owners of natural resources have an incentive to take into account the current price, the expected future demand for them, and the interest rate when making choices about resource supply.

- The services of a renewable natural resource may be consumed at levels that are below or greater than the carrying capacity of the resource.

- The payment for a resource above the minimum price necessary to make the resource available is economic rent.

TRY IT!

You have just been given an oil well in Texas by Aunt Carmen. The current price of oil is $45 per barrel, and it is estimated that your oil deposit contains about 10,000 barrels of oil. For simplicity, assume that it does not cost anything to extract the oil and get it to market and that you must decide whether to empty the well now or wait until next year. Suppose the interest rate is 10% and that you expect that the price of oil next year will rise to $54 per barrel. What should you do? Would your decision change if the choice were to empty the well now or in two years?

Case in Point: World Oil Dilemma

The world is going to need a great deal more oil. Perhaps soon.

The International Energy Agency, regarded as one of the world’s most reliable in assessing the global energy market, says that world oil production must increase from 87 million barrels per day in 2008 to 99 million barrels per day by 2015. Looking farther ahead, the situation gets scarier. Jad Mouawad reported in The New York Times that the number of cars and trucks in the world is expected to double—to 2 billion—in 30 years. The number of passenger jetliners in the world will double in 20 years. The IEA says that the demand for oil will increase by 35% by 2030. Meeting that demand would, according to the Times, require pumping an additional 11 billion barrels of oil each year—an increase of 13%.

Certainly some in Saudi Arabia, which holds a quarter of the world’s oil reserves, were sure it would be capable of meeting the world’s demand for oil, at least in the short term. In the summer of 2005, Peter Maass of The New York Times reported that Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, gave an upbeat report in Washington, D.C. to a group of world oil officials. With oil prices then around $55 a barrel, he said, “I want to assure you here today that Saudi Arabia’s reserves are plentiful, and we stand ready to increase output as the market dictates.” The minister may well have been speaking in earnest. But, according to the U. S. Energy Information Administration, Saudi Arabia’s oil production was 9.6 million barrels per day in 2005. It fell to 8.7 million barrels per day in 2006 and to 8.7 million barrels per day in 2007. The agency reports that world output also fell in each of those years. World oil prices soared to $147 per barrel in June of 2008. What happened?

Much of the explanation for the reduction in Saudi Arabia’s output in 2006 and 2007 can be found in one field. More than half of the country’s oil production comes from the Ghawar field, the most productive oil field in the world. Ghawar was discovered in 1948 and has provided the bulk of Saudi Arabia’s oil. It has given the kingdom and the world more than 5 million barrels of oil per day for well over 50 years. It is, however, beginning to lose pressure. To continue getting oil from it, the Saudis have begun injecting the field with seawater. That creates new pressure and allows continued, albeit somewhat reduced, production. Falling production at Ghawar has been at the heart of Saudi Arabia’s declining output.

The Saudi’s next big hope is an area known as the Khurais complex. An area about half the size of Connecticut, the Saudis are counting on Khurais to produce 1.2 million barrels per day beginning in 2009. If it does, it will be the world’s fourth largest oil field, behind Ghawar and fields in Mexico and Kuwait. Khurais, however, is no Ghawar. Not only is its expected yield much smaller, but it is going to be far more difficult to exploit. Khurais has no pressure of its own. To extract any oil from it, the Saudis will have to pump a massive amount of seawater from the Persian Gulf, which is 120 miles from Khurais. Injecting the water involves an extraordinary complex of pipes, filters, and more than 100 injection wells for the seawater. The whole project will cost a total of $15 billion. The Saudis told The Wall Street Journal that the development of the Khurais complex is the biggest industrial project underway in the world. The Saudis have used seismic technology to take more than 2.8 million 3-dimensional pictures of the deposit, trying to gain as complete an understanding of what lies beneath the surface as possible. The massive injection of seawater is risky. Done incorrectly, the introduction of the seawater could make the oil unusable.

Khurais illustrates a fundamental problem that the world faces as it contemplates its energy future. The field requires massive investment for an extraordinarily uncertain outcome, one that will only increase Saudi capacity from about 11.3 million barrels per day to 12.5.

Sadad al-Husseini, who until 2004 was the second in command at Aramco and is now a private energy consultant, doubts that Saudi Arabia will be able to achieve even that increase in output. He says that is true of the world in general, that the globe has already reached the maximum production it will ever achieve—the so-called “peak production” theory. What we face, he told The Wall Street Journal in 2008, is a grim future of depleting oil resources and rising prices.

Rising oil prices, of course, lead to greater conservation efforts, and the economic slump that took hold in the latter part of 2008 has led to a sharp reversal in oil prices. But, if “peak production” theory is valid, lower oil prices will not persist after world growth returns to normal. This idea is certainly one to consider as we watch the path of oil prices over the next few years.

Sources: Peter Maass, “The Breaking Point,” The New York Times Magazine Online, August 21, 2005; Jad Mouawad, “The Big Thirst,” The New York Times Online, April 20, 2008; US. Energy Information Administration, International Controlling a Monthly, May 2008, Table 4.1c; Neil King, Jr. “Saudis Face Hurdles in New Oil Drilling,” The Wall Street Journal, April 22, 2008, A1, Neil King, Jr. “Global Oil-Supply Worries Fuel Debate in Saudi Arabia,” The Wall Street Journal, June 27, 2008, A1.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

Since you expect oil prices to rise ($54 − 45)/$45 = 20% and the interest rate is only 10%, you would be better off waiting a year before emptying the well. Another way of seeing this is to compute the present value of the oil a year from now:

P0 = ($54*10,000)/(1+0.10)1 = $490,909.09

Since $490,909 is greater than the $45*10,000 = $450,000 you could earn by emptying the well now, the present value calculation shows the rewards of waiting a year.

If the choice is to empty the well now or in 2 years, however, you would be better off emptying it now, since the present value is only $446,280.99:

P0= ($54*10,000)/(1+0.10)2 = $446,280.99

- 5403 reads