The consumption of goods that can be easily stored, or whose consumption can be postponed, is strongly affected by buyer expectations. The expectation of newer TV technologies, such as high-definition TV, could slow down sales of regular TVs. If people expect gasoline prices to rise tomorrow, they will fill up their tanks today to try to beat the price increase. The same will be true for goods such as automobiles and washing machines: an expectation of higher prices in the future will lead to more purchases today. If the price of a good is expected to fall, however, people are likely to reduce their purchases today and await tomorrow’s lower prices. The expectation that computer prices will fall, for example, can reduce current demand.

Heads Up!

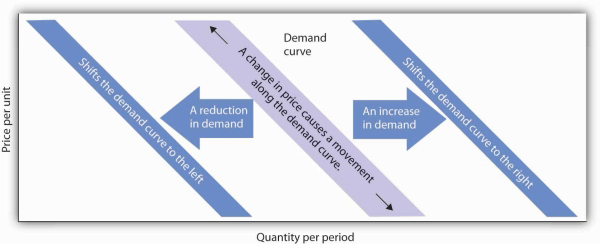

It is crucial to distinguish between a change in quantity demanded, which is a movement along the demand curve caused by a change in price, and a change in demand, which implies a shift of the demand curve itself. A change in demand is caused by a change in a demand shifter. An increase in demand is a shift of the demand curve to the right. A decrease in demand is a shift in the demand curve to the left. This drawing of a demand curve highlights the difference.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The quantity demanded of a good or service is the quantity buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand schedule is a table that shows the quantities of a good or service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- A demand curve shows graphically the quantities of a good or service demanded at different prices during a particular period, all other things unchanged.

- All other things unchanged, the law of demand holds that, for virtually all goods and services, a higher price induces a reduction in quantity demanded and a lower price induces an increase in quantity demanded.

- A change in the price of a good or service causes a change in the quantity demanded—a movement along the demand curve.

- A change in a demand shifter causes a change in demand, which is shown as a shift of the demand curve. Demand shifters include preferences, the prices of related goods and services, income, demographic characteristics, and buyer expectations.

- Two goods are substitutes if an increase in the price of one causes an increase in the demand for the other. Two goods are complements if an increase in the price of one causes a decrease in the demand for the other.

- A good is a normal good if an increase in income causes an increase in demand. A good is an inferior good if an increase in income causes a decrease in demand.

TRY IT!

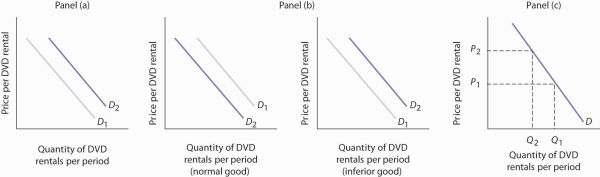

All other things unchanged, what happens to the demand curve for DVD rentals if there is (a) an increase in the price of movie theater tickets, (b) a decrease in family income, or (c) an increase in the price of DVD rentals? In answering this and other “Try It!” problems in this chapter, draw and carefully label a set of axes. On the horizontal axis of your graph, show the quantity of DVD rentals. It is necessary to specify the time period to which your quantity pertains (e.g., “per period,” “per week,” or “per year”). On the vertical axis show the price per DVD rental. Since you do not have specific data on prices and quantities demanded, make a “free-hand” drawing of the curve or curves you are asked to examine. Focus on the general shape and position of the curve(s) before and after events occur. Draw new curve(s) to show what happens in each of the circumstances given. The curves could shift to the left or to the right, or stay where they are.

Case in Point: Solving Campus Parking Problems Without Adding More Parking Spaces

Unless you attend a “virtual” campus, chances are you have engaged in more than one conversation about how hard it is to find a place to park on campus. Indeed, according to Clark Kerr, a former president of the University of California system, a university is best understood as a group of people “held together by a common grievance over parking.”

Clearly, the demand for campus parking spaces has grown substantially over the past few decades. In surveys conducted by Daniel Kenney, Ricardo Dumont, and Ginger Kenney, who work for the campus design company Sasaki and Associates, it was found that 7 out of 10 students own their own cars. They have interviewed “many students who confessed to driving from their dormitories to classes that were a five-minute walk away,” and they argue that the deterioration of college environments is largely attributable to the increased use of cars on campus and that colleges could better service their missions by not adding more parking spaces.

Since few universities charge enough for parking to even cover the cost of building and maintaining parking lots, the rest is paid for by all students as part of tuition. Their research shows that “for every 1,000 parking spaces, the median institution loses almost $400,000 a year for surface parking, and more than $1,200,000 for structural parking.” Fear of a backlash from students and their parents, as well as from faculty and staff, seems to explain why campus administrators do not simply raise the price of parking on campus.

While Kenney and his colleagues do advocate raising parking fees, if not all at once then over time, they also suggest some subtler, and perhaps politically more palatable, measures—in particular, shifting the demand for parking spaces to the left by lowering the prices of substitutes.

Two examples they noted were at the University of Washington and the University of Colorado at Boulder. At the University of Washington, car poolers may park for free. This innovation has reduced purchases of single-occupancy parking permits by 32% over a decade. According to University of Washington assistant director of transportation services Peter Dewey, “Without vigorously managing our parking and providing commuter alternatives, the university would have been faced with adding approximately 3,600 parking spaces, at a cost of over $100 million…The university has created opportunities to make capital investments in buildings supporting education instead of structures for cars.” At the University of Colorado, free public transit has increased use of buses and light rail from 300,000 to 2 million trips per year over the last decade. The increased use of mass transit has allowed the university to avoid constructing nearly 2,000 parking spaces, which has saved about $3.6 million annually.

Sources: Daniel R. Kenney, “How to Solve Campus Parking Problems Without Adding More Parking,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 26, 2004, Section B, pp. B22-B23.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

Since going to the movies is a substitute for watching a DVD at home, an increase in the price of going to the movies should cause more people to switch from going to the movies to staying at home and renting DVDs. Thus, the demand curve for DVD rentals will shift to the right when the price of movie theater tickets increases [Panel (a)].

A decrease in family income will cause the demand curve to shift to the left if DVD rentals are a normal good but to the right if DVD rentals are an inferior good. The latter may be the case for some families, since staying at home and watching DVDs is a cheaper form of entertainment than taking the family to the movies. For most others, however, DVD rentals are probably a normal good [Panel (b)].

An increase in the price of DVD rentals does not shift the demand curve for DVD rentals at all; rather, an increase in price, say from P1 to P2, is a movement upward to the left along the demand curve. At a higher price, people will rent fewer DVDs, say Q2 instead of Q1, ceteris paribus [Panel (c)].

- 5331 reads