We see in Figure 11.1 that Mama’s Pizza is earning an economic profit. If Mama’s experience is typical, then other firms in the market are also earning returns that exceed what their owners could be earning in some related activity. Positive economic profits will encourage new firms to enter Mama’s market.

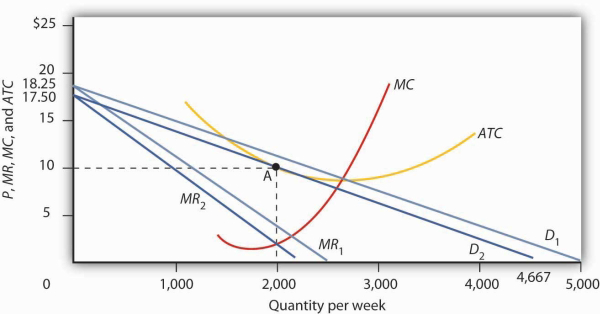

As new firms enter, the availability of substitutes for Mama’s pizzas will increase, which will reduce the demand facing Mama’s Pizza and make the demand curve for Mama’s Pizza more elastic. Its demand curve will shift to the left. Any shift in a demand curve shifts the marginal revenue curve as well. New firms will continue to enter, shifting the demand curves for existing firms to the left, until pizza firms such as Mama’s no longer make an economic profit. The zero-profit solution occurs where Mama’s demand curve is tangent to its average total cost curve—at point A in Figure 11.2. Mama’s price will fall to $10 per pizza and its output will fall to 2,000 pizzas per week. Mama’s will just cover its opportunity costs, and thus earn zero economic profit. At any other price, the firm’s cost per unit would be greater than the price at which a pizza could be sold, and the firm would sustain an economic loss. Thus, the firm and the industry are in long-run equilibrium. There is no incentive for firms to either enter or leave the industry.

The existence of economic profits in a monopolistically competitive industry will induce entry in the long run. As new firms enter, the demand curve D1 and marginal revenue curve MR1 facing a typical firm will shift to the left, to D2 and MR2. Eventually, this shift produces a profit-maximizing solution at zero economic profit, where D2 is tangent to the average total cost curve ATC (point A). The long-run equilibrium solution here is an output of 2,000 units per week at a price of $10 per unit.

Had Mama’s Pizza and other similar restaurants been incurring economic losses, the process of moving to long-run equilibrium would work in reverse. Some firms would exit. With fewer substitutes available, the demand curve faced by each remaining firm would shift to the right. Price and output at each restaurant would rise. Exit would continue until the industry was in long-run equilibrium, with the typical firm earning zero economic profit.

Such comings and goings are typical of monopolistic competition. Because entry and exit are easy, favorable economic conditions in the industry encourage start-ups. New firms hope that they can differentiate their products enough to make a go of it. Some will; others will not. Competitors to Mama’s may try to improve the ambience, play different music, offer pizzas of different sizes and types. It might take a while for other restaurants to come up with just the right product to pull customers and profits away from Mama’s. But as long as Mama’s continues to earn economic profits, there will be incentives for other firms to try.

Heads Up!

The term “monopolistic competition” is easy to confuse with the term “monopoly.” Remember, however, that the two models are characterized by quite different market conditions. A monopoly is a single firm with high barriers to entry. Monopolistic competition implies an industry with many firms, differentiated products, and easy entry and exit.

Why is the term monopolistic competition used to describe this type of market structure? The reason is that it bears some similarities to both perfect competition and to monopoly. Monopolistic competition is similar to perfect competition in that in both of these market structures many firms make up the industry and entry and exit are fairly easy. Monopolistic competition is similar to monopoly in that, like monopoly firms, monopolistically competitive firms have at least some discretion when it comes to setting prices. However, because monopolistically competitive firms produce goods that are close substitutes for those of rival firms, the degree of monopoly power that monopolistically competitive firms possess is very low.

- 3798 reads