Instead of focusing on associations between stimuli and responses, operant conditioning focuses on how the effects of consequences on behaviors. The operant model of learning begins with the idea that certain consequences tend to make certain behaviors happen more frequently. If I compliment a student for a good comment during a discussion, there is more of a chance that I will hear comments from the student more often in the future (and hopefully they will also be good ones!). If a student tells a joke to several classmates and they laugh at it, then the student is more likely to tell additional jokes in the future and so on.

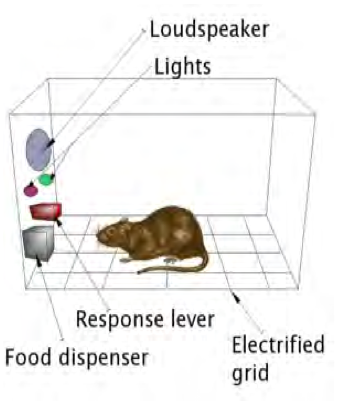

As with respondent conditioning, the original research about this model of learning was not done with people, but with animals. One of the pioneers in the field was a Harvard professor named B. F. Skinner, who published numerous books and articles about the details of the process and who pointed out many parallels between operant conditioning in animals and operant conditioning in humans (1938, 1948, 1988). Skinner observed the behavior of rather tame laboratory rats (not the unpleasant kind that sometimes live in garbage dumps). He or his assistants would put them in a cage that contained little except a lever and a small tray just big enough to hold a small amount of food. (Table 2.5 shows the basic set-up, which is sometimes nicknamed a “Skinner box_.) At first the rat would sniff and “putter around” the cage at random, but sooner or later it would happen upon the lever and eventually happen to press it. Presto! The lever released a small pellet of food, which the rat would promptly eat. Gradually the rat would spend more time near the lever and press the lever more frequently, getting food more frequently. Eventually it would spend most of its time at the lever and eating its fill of food. The rat had “discovered” that the consequence of pressing the level was to receive food. Skinner called the changes in the rat's behavior an example of operant conditioning, and gave special names to the different parts of the process. He called the food pellets the reinforcement and the lever-pressing the operant (because it "operated” on the rat's environment). See below.

|

Operant -> Reinforcement Press lever -> Food pellet |

|

Skinner and other behavioral psychologists experimented with using various reinforcers and operants. They also experimented with various patterns of reinforcement (or schedules of reinforcement), as well as with various cues or signals to the animal about when reinforcement was available. It turned out that all of these factors the operant, the reinforcement, the schedule, and the cues affected how easily and thoroughly operant conditioning occurred. For example, reinforcement was more effective if it came immediately after the crucial operant behavior, rather than being delayed, and reinforcements that happened intermittently (only part of the time) caused learning to take longer, but also caused it to last longer.

Operant conditioning and students' learning: As with respondent conditioning, it is important to ask whether operant conditioning also describes learning in human beings, and especially in students in classrooms. On this point the answer seems to be clearly yes”. There are countless classroom examples of consequences affecting students' behavior in ways that resemble operant conditioning, although the process certainly does not account for all forms of student learning (Alberto & Troutman, 2005). Consider the following examples. In most of them the operant behavior tends to become more frequent on repeated occasions:

- A seventh-grade boy makes a silly face (the operant) at the girl sitting next to him. Classmates sitting around them giggle in response (the reinforcement).

- A kindergarten child raises her hand in response to the teacher's question about a story (the operant). The teacher calls on her and she makes her comment (the reinforcement).

- Another kindergarten child blurts out her comment without being called on (the operant). The teacher frowns, ignores this behavior, but before the teacher calls on a different student, classmates are listening attentively (the reinforcement) to the student even though he did not raise his hand as he should have.

- A twelfth-grade student a member of the track team runs one mile during practice (the operant). He notes the time it takes him as well as his increase in speed since joining the team (the reinforcement).

- A child who is usually very restless sits for five minutes doing an assignment (the operant). The teaching assistant compliments him for working hard (the reinforcement).

- A sixth-grader takes home a book from the classroom library to read overnight (the operant). When she returns the book the next morning, her teacher puts a gold star by her name on a chart posted in the room (the reinforcement).

Hopefully these examples are enough to make four points about operant conditioning. First, the process is widespread in classrooms probably more widespread than respondent conditioning. This fact makes sense, given the nature of public education: to a large extent, teaching is about making certain consequences for students (like praise or marks) depend on students' engaging in certain activities (like reading certain material or doing assignments). Second, learning by operant conditioning is not confined to any particular grade, subject area, or style of teaching, but by nature happens in nearly every imaginable classroom. Third, teachers are not the only persons controlling reinforcements. Sometimes they are controlled by the activity itself (as in the track team example), or by classmates (as in the “giggling” example). A result of all of the above points is the fourth: that multiple examples of operant conditioning often happen at the same time.

The skill builder for this chapter (The decline and fall of Jane Gladstone) suggests how this happened to someone completing student teaching.

Because operant conditioning happens so widely, its effects on motivation are a bit more complex than the effects of respondent conditioning. As in respondent conditioning, operant conditioning can encourage intrinsic motivation to the extent that the reinforcement for an activity can sometimes be the activity itself. When a student reads a book for the sheer enjoyment of reading, for example, he is reinforced by the reading itself; then we often say that his reading is “intrinsically motivated”. More often, however, operant conditioning stimulates both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation at the same time. The combining of both is noticeable in the examples that I listed above. In each example, it is reasonable to assume that the student felt intrinsically motivated to some partial extent, even when reward came from outside the student as well.

This was because part of what reinforced their behavior was the behavior itself whether it was making faces, running a mile, or contributing to a discussion. At the same time, though, note that each student probably was also extrinsically motivated, meaning that another part of the reinforcement came from consequences or experiences not inherently part of the activity or behavior itself. The boy who made a face was reinforced not only by the pleasure of making a face, for example, but also by the giggles of classmates.

The track student was reinforced not only by the pleasure of running itself, but also by knowledge of his improved times and speeds. Even the usually restless child sitting still for five minutes may have been reinforced partly by this brief experience of unusually focused activity, even if he was also reinforced by the teacher aide's compliment. Note that the extrinsic part of the reinforcement may sometimes be more easily observed or noticed than the intrinsic part, which by definition may sometimes only be experienced within the individual and not also displayed outwardly. This latter fact may contribute to an impression that sometimes occurs, that operant conditioning is really just “bribery in disguise”, that only the external reinforcements operate on students' behavior. It is true that external reinforcement may sometimes alter the nature or strength of internal (or intrinsic) reinforcement, but this is not the same as saying that it destroys or replaces intrinsic reinforcement. But more about this issue later! (See especially Section 6.1, “Student motivation_.)

Comparing operant conditioning and respondent conditioning: Operant conditioning is made more complicated, but also more realistic, by many of the same concepts as used in respondent conditioning. In most cases, however, the additional concepts have slightly different meanings in each model of learning. Since this circumstance can make the terms confusing, let me explain the differences for three major concepts used in both models extinction, generalization, and discrimination. Then I will comment on two additional concepts schedules of reinforcement and cues that are sometimes also used in talking about both forms of conditioning, but that are important primarily for understanding operant conditioning. The explanations and comments are also summarized in Table 2.1: Reading readiness in students vs in teachers.

|

Term |

A defined in respondent conditioning |

As defined in operant conditioning |

|

Extinction |

Disappearance of an association between a conditioned stimulus and a conditioned response |

Disappearance of the operant behavior due to lack of reinforcement |

|

Generalization |

Ability of stimulus similar to the conditioned stimulus to elicit the conditioned response |

Tendency of behaviors similar to operant to be conditioned along with the original operant |

|

Discrimination |

Learning not to respond to stimuli that are similar to the originally conditioned stimulus |

Learning not to emit behaviors that are similar to the originally conditioned operant |

|

Schedule of Reinforcement |

The pattern or frequency by which a CS is paired with the UCS during learning |

The pattern or frequency by which a reinforcement is a consequence of an operant during learning |

|

Cue |

Not applicable |

Stimulus prior to the operant that signals the availability or not of reinforcement |

In both respondent and operant conditioning, extinction refers to the disappearance of “something”. In operant conditioning, what disappears is the operant behavior because of a lack of reinforcement. A student who stops receiving gold stars or compliments for prolific reading of library books, for example, may extinguish (i.e. decrease or stop) book-reading behavior. In respondent conditioning, on the other hand, what disappears is association between the conditioned stimulus (the CS) and the conditioned response (CR). If you stop smiling at a student, then the student may extinguish her association between you and her pleasurable response to your smile, or between your classroom and the student's pleasurable response to your smile.

In both forms of conditioning, generalization means that something “extra” gets conditioned if it is somehow similar to “something”. In operant conditioning, the extra conditioning is to behaviors similar to the original operant. If getting gold stars results in my reading more library books, then I may generalize this behavior to other similar activities, such as reading the newspaper, even if the activity is not reinforced directly. In respondent conditioning, however, the extra conditioning refers to stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus. If I am a student and I respond happily to my teacher's smiles, then I may find myself responding happily to other people (like my other teachers) to some extent, even if they do not smile at me. Generalization is a lot like the concept of transfer that I discussed early in this chapter, in that it is about extending prior learning to new situations or contexts. From the perspective of operant conditioning, though, what is being extended (or transferred” or generalized) is a behavior, not knowledge or skill.

In both forms of conditioning, discrimination means learning not to generalize. In operant conditioning, though, what is not being overgeneralized is the operant behavior. If I am a student who is being complimented (reinforced) for contributing to discussions, I must also learn to discriminate when to make verbal contributions from when not to make verbal contributions such as when classmates or the teacher are busy with other tasks. In respondent conditioning, what are not being overgeneralized are the conditioned stimuli that elicit the conditioned response. If I, as a student, learn to associate the mere sight of a smiling teacher with my own happy, contented behavior, then I also have to learn not to associate this same happy response with similar, but slightly different sights, such as a teacher looking annoyed.

In both forms of conditioning, the schedule of reinforcement refers to the pattern or frequency by which “something” is paired with “something else”. In operant conditioning, what is being paired is the pattern by which reinforcement is linked with the operant. If a teacher praises me for my work, does she do it every time, or only sometimes? Frequently or only once in awhile? In respondent conditioning, however, the schedule in question is the pattern by which the conditioned stimulus is paired with the unconditioned stimulus. If I am student with Mr Horrible as my teacher, does he scowl every time he is in the classroom, or only sometimes? Frequently or rarely?

Behavioral psychologists have studied schedules of reinforcement extensively (for example, Ferster, et al., 1997; Mazur, 2005), and found a number of interesting effects of different schedules. For teachers, however, the most important finding may be this: partial or intermittent schedules of reinforcement generally cause learning to take longer, but also cause extinction of learning to take longer. This dual principle is important for teachers because so much of the reinforcement we give is partial or intermittent. Typically, if I am teaching, I can compliment a student a lot of the time, for example, but there will inevitably be occasions when I cannot do so because I am busy elsewhere in the classroom. For teachers concerned both about motivating students and about minimizing inappropriate behaviors, this is both good news and bad. The good news is that the benefits of my praising students' constructive behavior will be more lasting, because they will not extinguish their constructive behaviors immediately if I fail to support them every single time they happen. The bad news is that students' negative behaviors may take longer to extinguish as well, because those too may have developed through partial reinforcement. A student who clowns around inappropriately in class, for example, may not be “supported” by classmates' laughter every time it happens, but only some of the time. Once the inappropriate behavior is learned, though, it will take somewhat longer to disappear even if everyone both teacher and classmates make a concerted effort to ignore (or extinguish) it.

Finally, behavioral psychologists have studied the effects of cues. In operant conditioning, a cue is a stimulus that happens just prior to the operant behavior and that signals that performing the behavior may lead to reinforcement. Its effect is much like discrimination learning in respondent conditioning, except that what is “discriminated” in this case is not a conditioned behavior that is re ex-like, but a voluntary action, the operant. In the original conditioning experiments, Skinner's rats were sometimes cued by the presence or absence of a small electric light in their cage. Reinforcement was associated with pressing a lever when, and only when, the light was on. In classrooms, cues are sometimes provided by the teacher or simply by the established routines of the class. Calling on a student to speak, for example, can be a cue that if the student does say something at that moment, then he or she may be reinforced with praise or acknowledgment. But if that cue does not occur if the student is not called on speaking may not be rewarded. In more everyday, non-behaviorist terms, the cue allows the student to learn when it is acceptable to speak, and when it is not.

- 15712 reads