Adrienne Watt

The project initiation phase is the first phase within the project management life cycle, as it involves starting up a new project. Within the initiation phase, the business problem or opportunity is identified, a solution is defined, a project is formed, and a project team is appointed to build and deliver the solution to the customer. A business case is created to define the problem or opportunity in detail and identify a preferred solution for implementation. The business case includes:

- A detailed description of the problem or opportunity with headings such as Introduction, Business Objectives, Problem/Opportunity Statement, Assumptions, and Constraints

- A list of the alternative solutions available

- An analysis of the business benefits, costs, risks, and issues

- A description of the preferred solution

- Main project requirements

- A summarized plan for implementation that includes a schedule and financial analysis

The project sponsor then approves the business case, and the required funding is allocated to proceed with a feasibility study. It is up to the project sponsor to determine if the project is worth undertaking and whether the project will be profitable to the organization. The completion and approval of the feasibility study triggers the beginning of the planning phase. The feasibility study may also show that the project is not worth pursuing and the project is terminated; thus the next phase never begins.

All projects are created for a reason. Someone identifies a need or an opportunity and devises a project to address that need. How well the project ultimately addresses that need defines the project’s success or failure.

The success of your project depends on the clarity and accuracy of your business case and whether people believe they can achieve it. Whenever you consider past experience, your business case is more realistic; and whenever you involve other people in the business case’s development, you encourage their commitment to achieving it.

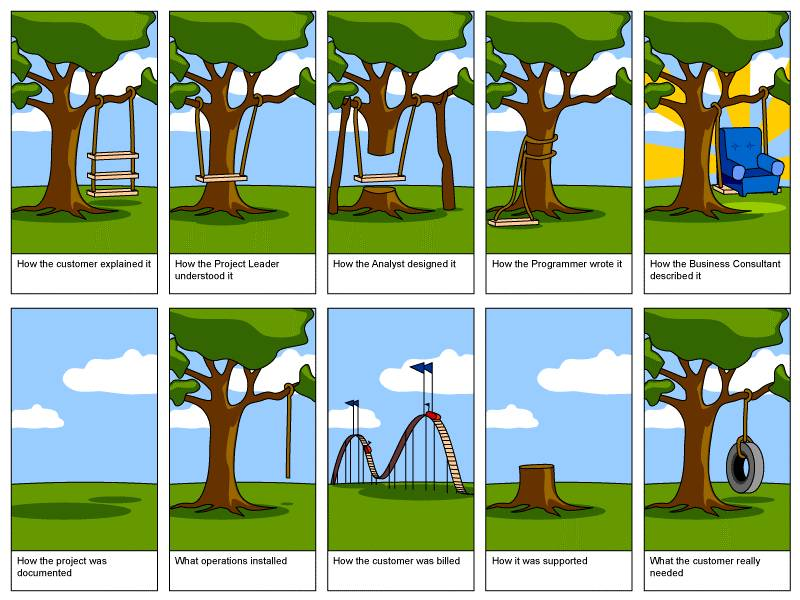

Often the pressure to get results encourages people to go right into identifying possible solutions without fully understanding the need or what the project is trying to accomplish. This strategy can create a lot of immediate activity, but it also creates significant chances for waste and mistakes if the wrong need is addressed. One of the best ways to gain approval for a project is to clearly identify the project’s objectives and describe the need or opportunity for which the project will provide a solution. For most of us, being misunderstood is a common occurrence, something that happens on a daily basis. At the restaurant, the waiter brings us our dinner and we note that the baked potato is filled with sour cream, even though we expressly requested “no sour cream.” Projects are filled with misunderstandings between customers and project staff. What the customer ordered (or more accurately what they think they ordered) is often not what they get. The cliché is “I know that’s what I said, but it’s not what I meant.” Figure 7.1 Project Management by Andreas Cappell demonstrates the importance of establishing clear objectives.

The need for establishing clear project objectives cannot be overstated. An objective or goal lacks clarity if, when shown to five people, it is interpreted in multiple ways. Ideally, if an objective is clear, you can show it to five people who, after reviewing it, hold a single view about its meaning. The best way to make an objective clear is to state it in such a way that it can be verified. Building in ways to measure achievement can do this. It is important to provide quantifiable definitions to qualitative terms.

For example, an objective of the team principle (project manager) of a Formula 1 racing team may be that their star driver, “finish the lap as fast as possible.” That objective is filled with ambiguity.

How fast is “fast as possible?” Does that mean the fastest lap time (the time to complete one lap) or does it mean the fastest speed as the car crosses the start/finish line (that is at the finish of the lap)?

By when should the driver be able to achieve the objective? It is no use having the fastest lap after the race has finished, and equally the fastest lap does not count for qualifying and therefore starting position, if it is performed during a practice session.

The ambiguity of this objective can be seen from the following example. Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher achieved the race lap record at the Circuit de Monaco of 1 min 14.439 sec in 2004 (Figure 7.2 Despite achieving the project goal of the “finish the lap as fast as possible,” Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher crashed 21 laps later and did not finish the race (top); Renault’s Jarno Trulli celebrating his win at the 2004 Monaco Grand Prix (middle); Jenson Button took his Brawn GP car to pole position at the Monaco Grand Prix with a lap time of 1 min 14.902 sec. He also went on to win the race, even though he did not achieve that lap time during the race (bottom). ). However, he achieved this on lap 23 of the race, but crashed on lap 44 of a 77-lap race. So while he achieved a fastest lap and therefore met the specific project goal of “finish the lap as fast as possible,” it did not result in winning the race, clearly a different project goal. In contrast, the fastest qualifying time at the same event was by Renault’s Jarno Trulli (1 min 13.985 sec), which gained him pole position for the race, which he went on to win (Figure 7.2 Despite achieving the project goal of the “finish the lap as fast as possible,” Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher crashed 21 laps later and did not finish the race (top); Renault’s Jarno Trulli celebrating his win at the 2004 Monaco Grand Prix (middle); Jenson Button took his Brawn GP car to pole position at the Monaco Grand Prix with a lap time of 1 min 14.902 sec. He also went on to win the race, even though he did not achieve that lap time during the race (bottom). ). In his case, he achieved the specific project goal of “finish the lap as fast as possible,” but also the larger goal of winning the race.

The objective can be strengthened considerably if it is stated as follows: “To be able to finish the 3.340 km lap at the Circuit de Monaco at the Monaco Grand Prix in 1 min 14.902 sec or less, during qualifying on May 23, 2009.” This was the project objective achieved by Brawn GP’s Jenson Button (Figure 7.2 Despite achieving the project goal of the “finish the lap as fast as possible,” Ferrari’s Michael Schumacher crashed 21 laps later and did not finish the race (top); Renault’s Jarno Trulli celebrating his win at the 2004 Monaco Grand Prix (middle); Jenson Button took his Brawn GP car to pole position at the Monaco Grand Prix with a lap time of 1 min 14.902 sec. He also went on to win the race, even though he did not achieve that lap time during the race (bottom). ).

There is still some ambiguity in this objective; for example, it assumes the star driver will be driving the team’s race car and not a rental car from Hertz. However, it clarifies the team principal’s intent quite nicely. It should be noted that a clear goal is not enough. It must also be achievable. The team principal’s goal becomes unachievable, for example, if he changes it to require his star driver to finish the 3.340 km lap in 30 sec or less.

To ensure the project’s objectives are achievable and realistic, they must be determined jointly by managers and those who perform the work. Realism is introduced because the people who will do the work have a good sense of what it takes to accomplish a particular task. In addition, this process assures some level of commitment on all sides: management expresses its commitment to support the work effort and workers demonstrate their willingness to do the work.

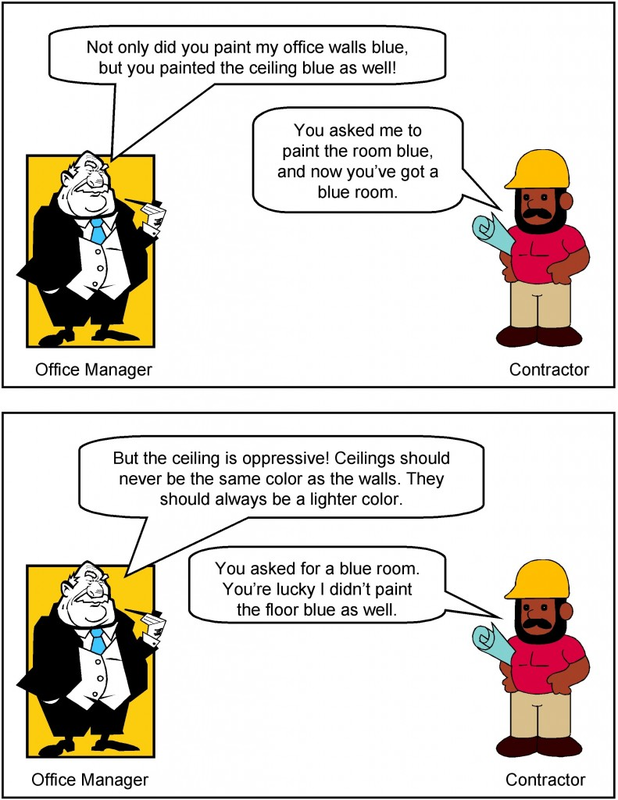

Imagine an office manager has contracted a painter to paint his office. His goal or objective is to have the office painted a pleasing blue color. Consider the conversation that occurs in Figure 7.3 The consequence of not making your objective clear. after the job was finished.

This conversation captures in a nutshell the essence of a major source of misunderstandings on projects: the importance of setting clear objectives. The office manager’s description of how he wanted the room painted meant one thing to him and another to the painter. As a consequence, the room was not painted to the office manager’s satisfaction. Had his objective been more clearly defined, he probably would have had what he wanted.

- 3100 reads