The economic characteristics of tourism explain the types of impact that tourism has on a community. There are five distinguishing characteristics. First, the tourist product cannot be stored; second, demand is highly seasonal. This means that in some months there is great activity while in other months there is little in the way of business. Pressure is put on businesses to make sufficient income during the season to sustain the business during the off season. Businesses can attempt one of two strategies:

Strategy 1: Alter supply to meet demand. This might mean meeting peak demand by reducing the quality of services provided or cutting off supply at a level lower than peak. For example, a restaurant might add tables during the peak season. More people could be served but customers would be cramped. Alternatively, service could be maintained but fewer customers served.

Strategy 2: Modify demand to meet supply. The supply of facilities is constant year-round. This strategy involves offering such things as cheaper prices in order to induce demand in the off-season to fill up places.

Third, demand is influenced by outside and unpredictable influences. Changes in currency exchange rates, political unrest, even changes in the weather can affect demand.

Demand is, fourthly, a function of many complex motivations. Tourists travel for more than one reason. There is also little brand loyalty on the part of most tourists. That is, most tourists are inclined to visit a different spot each year rather than return to the same place every vacation. This puts great pressure on the destination to select carefully the segments of the market it is going after.

Finally, tourism is price and income elastic. Demand will be greatly influenced by relatively small changes in price and income. Price elasticity refers to the relationship between the price charged and the amount demanded. When demand is price elastic it means that a small change in the price will result in a larger amount demanded and that total revenue generated will increase. The same is true for a demand that is income elastic; changes in demand are linked to changes in income.

Direct and indirect economic impact

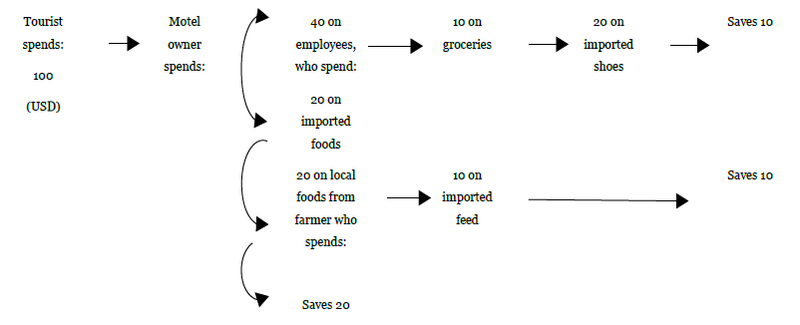

The economic impact of tourism is both direct and indirect. The direct effect comes from the actual money spent by tourists at a destination. When a tourist pays a motel owner USD 100 for a two-night stay, the USD 100 has a direct economic impact.

Indirect effects occur as the impact of the original USD 100 is felt on the economy. The motel owner might take the USD 100 and use some of it to pay for food for the restaurant and some of it to pay the wages of the motel's employees. The food supplier, in turn, will pay the farmer for the crops while the employee might buy a pair of shoes. The impact of the original USD 100 is increased.

The money will continue to be spent and re-spent until one of two things happen: The money is saved instead of spent or the money is spent outside the community. In both cases "leakage" occurs. When money is saved it is taken out of circulation as far as the generation of income is concerned. Similarly, when a hotel in the Bahamas pays for steaks imported from the United States, the economic impact is felt in the United States and not in the Bahamas. The more that a community can cut down on imports resulting from tourism, the greater will be the economic impact of tourism on that community. The USD 100 spent by the original tourist is re-spent by the motel owner, the employee and the farmer to generate income in the local economy of more than USD 100. Conversely, money spent on imports or money that is saved is removed from the local economy.

Income multiplier. The direct and indirect effects of an infusion of income into an area is termed the "multiplier”. Multipliers can be generated in terms of sales, income, employment or payroll.

We have seen that the initial spending of money by a tourist will generate more than that in income to the community. In order to know how much more, it is necessary to know something about what happens to money in the community. As noted above, the motel owner can do several things with the income brought in by tourists. First, money can be either saved or spent. And it can be spent locally or spent outside the community. As far as the community is concerned, saving the money is similar to spending it outside the community. The effect is the same, the income-producing potential is lost. The extent to which someone spends part of an extra dollar of income is termed the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). The extent to which an individual will save part of extra income is termed the marginal propensity to save (MPS). The more self-sufficient the community, the less will be the imports and the more the MPC.

The income multiplier is 1/MPS. If, in the above example, the motel owner saved USD 60, the income multiplier would be 1/0.6 or 1.67. If this effect was the same throughout the community it would mean that every USD 100 spent by tourists would generate USD 167 of income for the community.

Multipliers vary greatly by country. Most island economies have income multipliers between 0.6 and 1.2, whereas developed economies have a range between 1.7 and 2.0. The income multiplier for the Cayman Islands, for example, is 0.650, and that for the United Kingdom anywhere from 1.7 to 1.8. The output or sales multiplier for the United States is 2.96.

Employment multiplier. Increased spending as a result of tourist spending creates jobs. This results in an employment multiplier. The employment multiplier for the United States is 2.23. This means that, for every person directly involved in a tourism job (hotel receptionist, tour guide, etc) an additional 1.23 jobs are created in other industries.

Payroll multiplier. This results in another multiplier, the payroll multiplier. The payroll multiplier is the wages generated by these additional jobs. Again, for the United States, it is estimated that the payroll multiplier is 3.4. This is higher than the employment multiplier because, while many tourism jobs are low paying, tourism generates other jobs in higher-paying industries.

Economic benefits

Tourism contributes to foreign-exchange earnings, generates income and jobs, can improve economic structures and encourages small business development.

Foreign-exchange earnings

The balance of payments for a country is the relationship between its payments to the rest of the world and the money received from the rest of the world. When one country buys something from another country it is an import; when one country sells something to another country it is an export. Countries strive to achieve a positive balance of payments. Because most have trouble doing this, attracting tourists (who are regarded as "exports") is encouraged as a way of helping the balance of payments. On the other hand, when residents of a country vacation abroad, that is regarded as an import (because money leaves the home country). Some countries work to attract foreign tourists while keeping their own. For example, in 1969 the British government would allow people to take a maximum of only GBP 50 spending money out of Great Britain.

Effects on the economy are either direct or indirect. The direct effect is the actual expenditure by the tourists. Indirect, or secondary, impact is what happens as the money flows through the economy. Tourist spending creates such things as spending on marketing overseas, the paying of commissions to travel agents, purchases of goods and services by the original recipient of the tourist's payment and the wages paid to the employees of these goods and service companies.

Propensity to import. Several factors determine the extent to which a destination benefits from an infusion of foreign tourist money. These are the difference between the gross income (the money brought in) and the net income (the money kept). The factors are the extent to which the country imports, the amount of foreign labor used and the type of capital investment.

When tourists from, say, the United States are attracted to a destination they bring with them not only their money but also a demand for items of which they are accustom. They may want steaks, for example, for dinner. If the destination does not have beef of a suitable quantity or quality, it must import the beef to satisfy the tourist. The result is that some of the money spent by the tourist on the steak is used to pay a supplier outside the country for it. The steak is imported and the payment for it reduces the economic benefit of tourism to the destination.

Developing countries are less self-sufficient than are developed economies and are more liable to have to import such things as foodstuffs, beverages, construction materials and supplies. Developed countries have backward linkages; economic links between the sectors of the economy such that the domestic economy provides the grain to make the buns and the beef to make the hamburgers to sell to the tourist.

The propensity to import is the amount of each additional unit of tourist expenditure that is used to buy imports. It is estimated, for example, that the import propensity for the US state of Hawaii is 45 per cent. This means that, for every dollar spent in Hawaii by tourists, USD 45 cents is used to import goods and services to serve these tourists. The more a country can have the tourist buy souvenirs made locally, eat food grown locally, and stay in hotels constructed of local materials, the more the tourist money will stay in the country.

Foreign labor. Many countries use foreign labor in serving the tourist. The hotel industry in England, for example, employs many Spaniards and Portuguese. In some cases it is because the locals will not do the work; in other situations it is because the locals do not have the skills. It was learned, for example, that almost two-thirds of employees in managerial and administrative positions in the Cayman Islands were expatriates. The result is that money paid in wages to the employee is spent not in the destination but in the employee's home country. The hotel employee from Portugal sends money home each week, lives on very little and returns to Portugal at the end of the season with his or her co-workers from Portugal. A number of countries are now requiring that, after a certain period of time, most managers of foreign-owned properties should be locals. They encourage the company to develop local people for managerial positions.

Capital investment. In the initial stages of tourism development a great deal of money is required for infrastructure and facilities. Most lesser-developed countries cannot afford to finance construction internally and must turn to foreign countries and corporations for assistance. The foreign companies come in, build the facilities, attract the tourists and send the profits out of the country. The destination needs the influx of foreign money to develop the tourism potential; it loses control (and profits) from the venture.

Because of these factors, leakage from the local economy can be high. For developing countries, tourism has not brought the foreign-exchange benefits once thought possible.

Income generation

The income from tourism contributes to the gross national product of a country. The tourism contribution is the money spent by tourists minus the purchases by the tourism sector to service these tourists. In most developed and many lesser-developed countries the percentage share of international tourist receipts in the gross national product is low, typically between 0.3 and 7 per cent. Adding in the effects of domestic tourism increases the percentage significantly because domestic tourism is usually much more extensive than foreign tourism.

The total income generated depends on the multiplier effect noted above. Different sectors of the industry produce more income than others. Income generated is a reflection of the total amount spent and the amount of leakage within that sector. It has been found, for example, that bed-and-breakfast places have relatively low leakage because of their ability to buy what they need locally. However, they produce much less revenue initially compared to a large hotel, which will have a smaller multiplier effect because of its need to purchase goods and services outside the destination.

Certain sectors of the economy benefit from tourism more than others. The primary industry beneficiaries of tourist spending are food and beverage, lodging, transportation and retailing. A strong secondary effect is felt in real estate, auto services and repair and trucking.

Government revenues. Tourism income accrues to the government in three ways: from direct taxation on employees as well as goods and services; from indirect taxation such as customs duties; and from revenue generated by government-owned businesses. The Bahamian government, for example, estimates tourist revenue from the following sources:

- customs duties

- excise duties

- real property tax

- motor vehicle tax

- gaming taxes

- stamp tax

- services of a commercial nature

- fees and service charges

- revenue from government property

- interest

- reimbursement and loan repayment

Employment

It is estimated that over 60 million jobs worldwide are generated both directly and indirectly by foreign visitors and domestic travelers journeying to places 64 kilometers or more from home. 33,000 jobs are created for every USD 1 billion of spending in OECD countries, while the same amount generates 50,000 jobs in the rest of the world.

Several points can be made. First, there is a close, though not perfect, relationship between employment and income. There is both a direct and an indirect effect for both. Direct employment would be for jobs that directly result form tourist expenditures. Indirect employment is generated from jobs resulting from the effects of the tourist expenditures. Trinidad and Tobago, for example, estimates that three jobs are generated by the creation of every two hotel rooms. Multiplier effects are not identical, however.

Second, it can be noted that the type of tourist activity affects the type and number of jobs generated. Accommodation facilities, for example, tend to be more labor intensive than other tourism businesses. They are also highly capital intensive; large amounts of capital are required to create a job.

Third, the type of skills available locally affects employment generated. Most tourism jobs require little skill. The number of managerial positions are relatively small and, as mentioned earlier, are often occupied by non-locals. Tourism industries also rely heavily on females. There is, thus, great demand for unskilled workers who are often female. Critics have argued that tourism offers low-paying jobs that are seasonal in nature. There is limited opportunity to increase productivity because of the service nature of the positions. Because of this, it is argued that tourism can have a depressing effect on economic growth.

Others argue that the employment benefits of tourism are disguised.

Tourism, they say, takes people from other sectors of the economy, especially rural people, or those not normally considered part of the available work force, such as married mothers, the retired or those outside the national economy. The question then arises: does tourism generate new jobs or merely shuffle jobs around?

Finally, the seasonal nature of tourism should be stressed. While seasonal jobs are attractive to students and some teachers, they can discourage people from year-round, more productive work.

Small business development

Many tourism businesses are small, family-owned concerns. It might be a taxi service, a souvenir shop or a small restaurant. The extent to which the direct employers such as hotels and transportation companies can develop links to other sectors of the economy will determine how many jobs and how much income tourism can generate. Too often, when massive development of tourism occurs in developing countries, local suppliers cannot supply the quantity or quality of goods desired. As a result, good are imported, leakage occurs and potential income and jobs are lost.

The extent to which tourism can establish ties with local businesses depends upon the following factors:

- the types of supplies and producers with which the industry's demands are linked;

- the capacity of local suppliers to meet these demands;

- the historical development of tourism in the destination area;

- the type of tourism development. 1

More and more tourists seek authenticity as they travel. If this can be translated into buying locally produced souvenirs and eating locally produced food and staying in rooms furnished with local artifacts, then tourism will have generated the backward linkages necessary to contribute to the economy.

Economic structure. Tourism alters the economic structure of destinations. There is no agreement, however, as to how positive the alterations might be. A major change when tourism is developed is the change in jobs of rural people. There is a tendency for farmers to leave the land to pursue what are, for them, better jobs in tourism. This can put rural lands in jeopardy. Changes in land use are also common. Often less developed areas have only two things on which to build an economy: agriculture and tourism. As tourism develops, competition for the land occurs. The price of land increases; people sell. While a few benefit, it is difficult for locals to buy their own piece of land.

On the other hand, tourism can help reverse the depopulation of rural areas. In the Scottish Highlands, for example, the woman who takes in bed-and-breakfast guests may be married to the local postmaster. If tourism were to falter, the community might lose not only a bed-and-breakfast establishment, but also the postmaster.

Economic costs

There are a number of economic concerns about tourism.

Inflation and land values. As noted above, tourism development raises both the price of land and the prices of other goods and services. Even if a local resident does not sell, his or her costs increase as property taxes rise. In the five years following the acquisition of land in the US state of Florida for Disney World, land values surrounding the attraction increased significantly. The land was originally purchased under assumed names for USD 350 an acre (0.4 hectares). Five years later the surrounding land brought upwards of USD 150,000 an acre!

Seasonality. Most tourism destinations are seasonal; many hospitality facilities close down during the off season. However, large amounts of capital are necessary to build these facilities. Interest costs are high on the capital needed for construction. Interest costs are also fixed; they must be paid irrespective of the amount of business generated. As a result of high fixed costs and seasonal demand, there is constant pressure to produce a profit in what some call "the hundred-day season”. As a result of underutilization of the investment on a year-round basis, the return on investment is often less than that generated in other industries.

Often financial incentives from the public sector are necessary to get tourist facilities built.

Public services. Tourism is touted as a "smokeless industry" that requires few public services. Schools do not have to be built for the children of tourists, whereas they must be constructed for the children of workers brought in to work full time in other industries.

However, an increase in tourism tends to increase the costs for residents in such areas as garbage collection, police and fire protection.

Opportunity costs. When governments invest scarce resources in encouraging the development of tourism they forego the opportunity to invest that money in other, perhaps more productive, ways. This is known as opportunity cost. It does appear that investments in tourism yield returns comparable to returns in other industries. Both the private and public sectors, however, should be aware that an investment in tourism facilities may be made at the expense of other sectors of the economy.

Over-dependence on tourism. It is generally agreed that it is unwise to base an economy on tourism. Tourism growth is affected by changes both internal (price increases and changes in fashion) and external (political problems, energy availability and currency fluctuations). Just as an individual property can rely too heavily on one segment of the market, so too a destination can rely too heavily on tourism. The key is to develop a balanced economy.

In a "traditional" development, a country's economy shifts from the primary sector (farming, mining, fishing, etc.) to the manufacturing or secondary sector to the service sector. For destinations that have only agriculture and tourism, the economy "misses" the middle stage of development. It is as if there is the lack of a foundation on which to build a strong service sector. This is the danger of an over-dependence on tourism.

- 46334 reads