Consumer demands are affected by incomes. Demand, after all, reflects ability as well as willingness to pay for goods and services. The market will be more responsive to the preferences of people with high incomes than to those of people with low incomes.

In a market that satisfies the efficiency condition, an efficient allocation of resources will emerge from any particular distribution of income. Different income distributions will result in different, but still efficient, outcomes. For example, if 1% of the population controls virtually all the income, then the market will efficiently allocate virtually all its production to those same people.

What is a fair, or equitable, distribution of income? What is an unfair distribution? Should everyone have the same income? Is the current distribution fair? Should the rich have less and the poor have more? Should the middle class have more? Equity is very much in the mind of the observer. What may seem equitable to one person may seem inequitable to another. There is, however, no test we can apply to determine whether the distribution of income is or is not equitable. That question requires a normative judgment.

Determining whether the allocation of resources is or is not efficient is one problem. Determining whether the distribution of income is fair is another. The governments of all nations act in some way to redistribute income. That fact suggests that people generally have concluded that leaving the distribution of income solely to the market would not be fair and that some redistribution is desirable. This may take the form of higher taxes for people with higher incomes than for those with lower incomes. It may take the form of special programs, such as welfare programs, for low-income people.

Whatever distribution society chooses, an efficient allocation of resources is still preferred to an inefficient one. Because an efficient allocation maximizes net benefits, the gain in net benefits could be distributed in a way that leaves all people better off than they would be at any inefficient allocation. If an efficient allocation of resources seems unfair, it must be because the distribution of income is unfair.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In a competitive system in which the interaction of demand and supply determine prices, the corresponding demand and supply curves can be considered marginal benefit and marginal cost curves, respectively.

- An efficient allocation of resources is one that maximizes the net benefit of each activity. We expect it to be achieved in markets that satisfy the efficiency condition, which requires a competitive market and well-defined, transferable property rights.

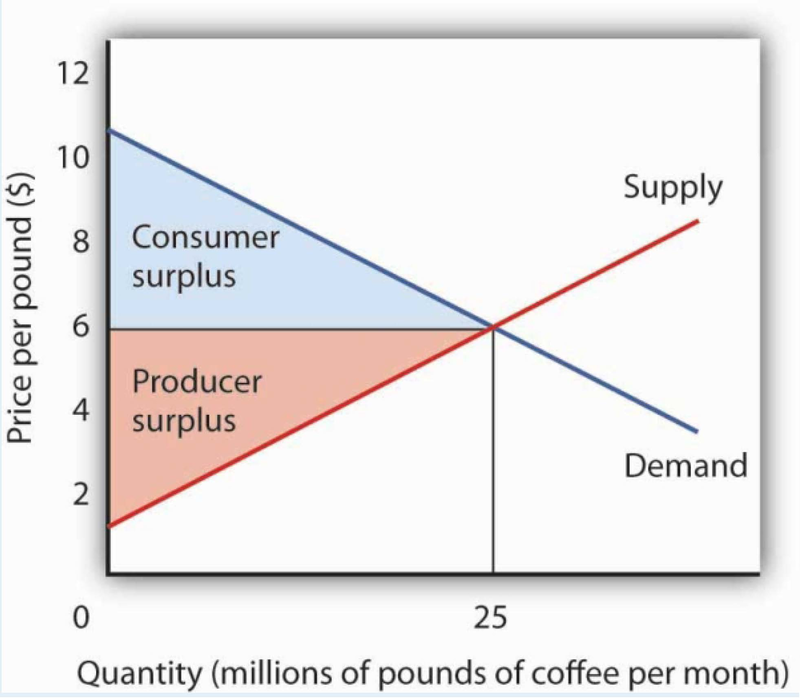

- Consumer surplus is the amount by which the total benefit to consumers from some activity exceeds their total expenditures for it.

- Producer surplus is the amount by which the total revenues of producers exceed their total costs.

- An inequitable allocation of resources implies that the distribution of income and wealth is inequitable. Judgments about equity are normative judgments.

TRY IT!

Draw hypothetical demand and supply curves for a typical product, say coffee. Now show the areas of consumer and producer surplus. Under what circumstances is the market likely to be efficient?

Case in Point: Saving the Elephant Through Property Rights

The African elephant, the world’s largest land mammal, seemed to be in danger of extinction in the 20th century. The population of African elephants fell from 1.3 million in 1979 to 543,000 in 1994. The most dramatic loss of elephants came in Kenya, where the population fell from 167,000 early in the 1970s to about 26,000 in 1997, according to the World Wildlife Fund. To combat the slaughter, an international agreement, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), went into effect in 1989. It banned the sale of ivory.

Despite CITES and armed patrols with orders to shoot poachers on sight, the poachers continued to operate in Kenya, killing roughly 200 elephants per day. The elephants were killed for their ivory; the tusks from a single animal could be sold for $2,000 in the black market—nearly double the annual per capita income in Kenya.

Several African nations, however, have taken a radically different approach. They have established exclusive, transferable property rights in licenses to hunt elephants. In each of these nations, elephant populations have increased. These nations include Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In Botswana, for example, the elephant population increased from 20,000 in 1981 to 80,000 in 2000. Zimbabwe increased its elephant population from 30,000 in 1978 to nearly 90,000 in 2000.

Professors Michael A. McPherson and Michael L. Nieswiadomy of the University of North Texas have done a statistical analysis of the determinants of elephant populations in 35 African nations. They found that elephant populations increased in nations that had (a) established exclusive, transferable property rights in licenses to hunt elephants and (b) had stable political systems. Conversely, elephant populations declined in countries that had failed to establish property rights and that had unstable political systems.

The same appears to be true of the white rhinoceros, a creature whose horns are highly valued in Asia as an aphrodisiac. South Africa sells permits to hunt the creatures for $25,000 per animal. Its rhinoceros herd has increased from 20 in 1900 to more than 7,000 by the late 1990s.

There is no “secret” to the preservation of species. Establishing clearly defined, transferable property rights virtually assures the preservation of species. Whether it be buffaloes, rhinoceroses, or elephants, property rights establish a market, and that market preserves species.

Sources: Lisa Grainger, “Are They Safe in Our Hands?” The Times of London (July 16, 1994): p. 18; Michael A. McPherson and Michael L. Nieswiadomy, “African Elephants: The Effect of Property Rights and Political Stability,” Contemporary Economic Policy, 18(1) (January 2000): 14–26; “Tusks and Horns and Conservationists,” The Economist, 343(8019) (May 31, 1997): 44.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

On the assumption that the coffee market is competitive and that it is characterized by well-defined exclusive and transferable property rights, the coffee market meets the efficiency

condition. That means that the allocation of resources shown at the equilibrium will be the one that maximizes the net benefit of all activities. The net benefit is shared by coffee consumers

(as measured by consumer surplus) and coffee producers (as measured by producer surplus).

- 瀏覽次數:3170