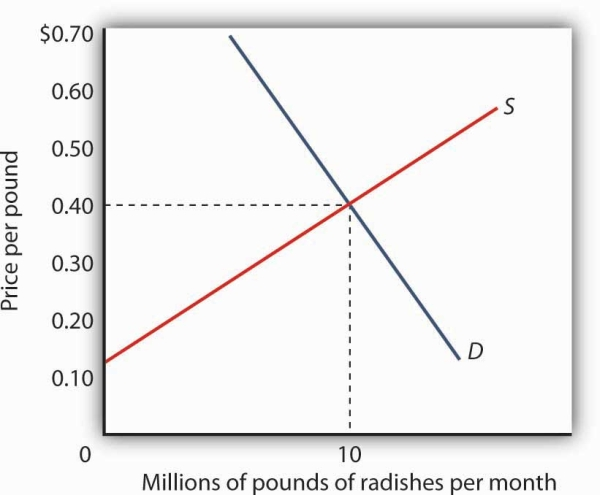

Each firm in a perfectly competitive market is a price taker; the equilibrium price and industry output are determined by demand and supply. Figure 9.2 shows how demand and supply in the market for radishes, which we shall assume are produced under conditions of perfect competition, determine total output and price. The equilibrium price is $0.40 per pound; the equilibrium quantity is 10 million pounds per month.

Price and output in a competitive market are determined by demand and supply. In the market for radishes, the equilibrium price is $0.40 per pound; 10 million pounds per month are produced and purchased at this price.

Because it is a price taker, each firm in the radish industry assumes it can sell all the radishes it wants at a price of $0.40 per pound. No matter how many or how few radishes it produces, the firm expects to sell them all at the market price.

The assumption that the firm expects to sell all the radishes it wants at the market price is crucial. If a firm did not expect to sell all of its radishes at the market price—if it had to lower the price to sell some quantities—the firm would not be a price taker. And price-taking behavior is central to the model of perfect competition.

Radish growers—and perfectly competitive firms in general—have no reason to charge a price lower than the market price. Because buyers have complete information and because we assume each firm’s product is identical to that of its rivals, firms are unable to charge a price higher than the market price. For perfectly competitive firms, the price is very much like the weather: they may complain about it, but in perfect competition there is nothing any of them can do about it.

- 瀏覽次數:2692