Boris Yeltsin, the first elected president of Russia, had been a leading proponent of market capitalism even before the Soviet Union collapsed. He had supported the Shatalin plan and had been sharply critical of Mr. Gorbachev’s failure to implement it. Once Russia became an independent republic, Mr. Yeltsin sought a rapid transition to market capitalism.

Mr. Yeltsin’s reform efforts, however, were slowed by Russian legislators, most of them former Communist officials who were appointed to their posts under the old regime. They fought reform and repeatedly sought to impeach Mr. Yeltsin. Citing health reasons, he abruptly resigned from the presidency in 1999, and appointed Vladimir Putin, who had only recently been appointed as Yeltsin’s prime minister, as acting president. Mr. Putin has since been elected and re-elected, though many observers have questioned the fairness of those elections as well as Mr. Putin’s commitment to democracy. Barred constitutionally from re-election in 2008, Putin became prime minister. Dimitry Medvedev, Putin’s close ally, became president.

Despite the hurdles, Russian reformers have accomplished a great deal. Prices of most goods have been freed from state controls. Most state-owned firms have been privatized, and most of Russia’s output of goods and services is now produced by the private sector.

To privatize state firms, Russian citizens were issued vouchers that could be used to purchase state enterprises. Under this plan, state enterprises were auctioned off. Individuals, or groups of individuals, could use their vouchers to bid on them. By 1995 most state enterprises in Russia had been privatized.

While Russia has taken major steps toward transforming itself into a market economy, it has not been able to institute its reforms in a coherent manner. For example, despite privatization, restructuring of Russian firms to increase efficiency has been slow. Establishment and enforcement of rules and laws that undergird modern, market-based systems have been lacking in Russia. Corruption has become endemic.

While the quality of the data is suspect, there is no doubt that output and the standard of living fell through the first half of the 1990s. Despite a financial crisis in 1998, when the Russian government defaulted on its debt, output recovered through the last half of the 1990s and Russia has seen substantial growth in the early years of the twenty-first century. In addition, government finances have improved following a major tax reform and inflation has come down from near hyperinflation levels. Despite these gains, there is uneasiness about the long-term sustainability of this progress because of the over-importance of oil and high oil prices in the recovery. Mr. Putin’s fight, whether justified or not, with several of Russia’s so-called oligarchs, a small group of people who were able to amass large fortunes during the early years of privatization, creates unease for domestic and foreign investors.

To be fair, overcoming the legacy of the Soviet Union would have been difficult at best. Overall, though, most would argue that Russian transition policies have made a difficult situation worse. Why has the transition in Russia been so difficult? One reason may be that Russians lived with command socialism longer than did any other country. In addition, Russia had no historical experience with market capitalism. In countries that did have it, such as the Czech Republic, the switch back to capitalism has gone far more smoothly and has met with far more success.

TRY IT!

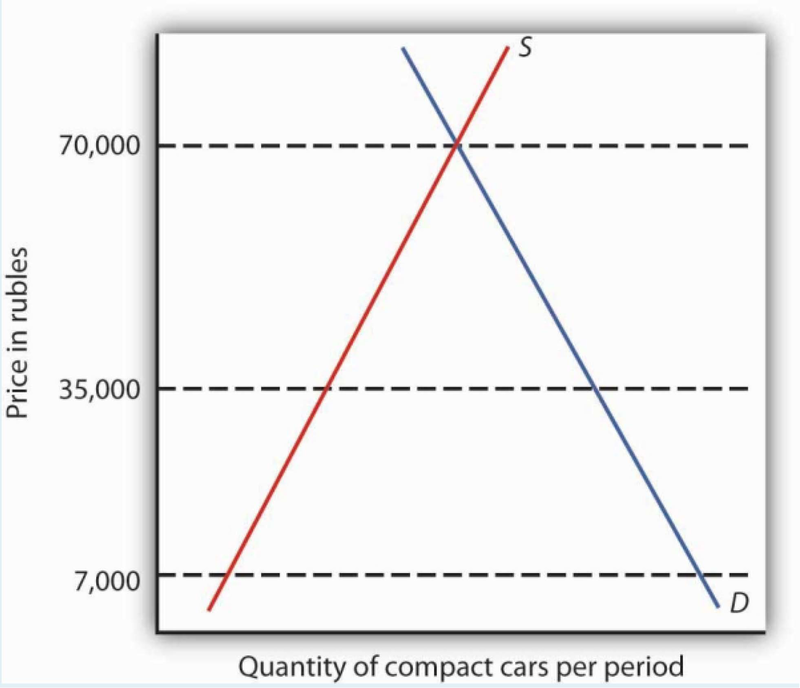

Table 20.1 shows three prices for various goods in the Soviet Union in 1991. Illustrate the market for compact cars using a demand and supply diagram. On your diagram, show the old price, the new

price, and the black market price.

Case in Point: Eastern Germany’s Surprisingly Difficult Transition Experience

The transition of eastern Germany was supposed to be the easiest of them all. Quickly merged with western Germany, given its new “Big Brother’s” deep pockets, the ease with which it could simply adopt the rules and laws and policies of western Germany, and its automatic entry into the European Union, how could it not do well? And yet, eastern Germany seems to be languishing while some other central European countries that had also been part of the Soviet bloc are doing much better. Specifically, growth in real GDP in eastern Germany was 6% to 8% in the early 1990s, but since then has mostly been around 1%, with three years of negative growth in the early 2000s. In the early 1990s, the Polish economy grew at less than half east Germany’s rate, but since then has averaged more than 4% per year. Why the reversal of fortunes?

Most observers point to the quick rise of wages to western German levels, despite the low productivity in the east. Initially, Germans from both east and west supported the move. East Germans obviously liked the idea of huge wage increases while west German workers thought that prolonged low wages in the eastern part of the country would cause companies to relocate there and saw the higher east German wages as protecting their own jobs. While the German government offered subsidies and tax breaks to firms that would move to the east despite the high wages, companies were by and large still reluctant to move their factories there. Instead they chose to relocate in other central European countries, such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland. As a result, unemployment in eastern Germany has remained stubbornly high at about 15% and transfer payments to east Germans have totaled $1.65 trillion with no end in sight. “East Germany had the wrong prices: Labor was too expensive, and capital was too cheap,” commented Klaus Deutsch, an economist at Deutsche Bank.

While the flow of labor has primarily been from Poland to Germany since the break-up of the Soviet bloc, with mostly senior managers moving from Germany to Poland, there are some less-skilled, unemployed east Germans who are starting to look for jobs in Poland. Tassilo Schlicht is an east German who repaired bicycles and washing machines at a Soviet-era factory and lost his job in 1990. He then worked for a short time at a gas station in his town for no pay with the hope that the experience would be helpful, but he was never hired. He undertook some government-sponsored retraining but still could not find a job. Finally, he was hired at a gas station across the border in Poland. The pay is far less than what employed Germans make for doing similar jobs but it is twice what he had been receiving in unemployment benefits. “These days, a job is a job, wherever it is.”

Sources: Marcus Walker and Matthew Karnitschnig, “Eastern Europe Eclipses Eastern Germany,”Wall Street Journal, November 9, 2004, p. A16; Keven J. O’Brien, “For Jobs, Some Germans Look to Poland,” New York Times, January 8, 2004, p. W1; Doug Saunders, “What’s the Matter with Eastern Germany?” The Globe and Mail (Canada), November 27, 2007, p. F3.

TRY IT!

There is a shortage of cars at both the old price of 7,000 rubles and at the new price of 35,000, although the shortage is less at the new price. Equilibrium price is assumed to be 70,000 rubles.

- 瀏覽次數:3158