In our examination of entry and exit in response to economic profit or loss in a perfectly competitive industry, we assumed that the ATC curve of a single firm does not shift as new firms enter or existing firms leave the industry. That is the case when expansion or contraction does not affect prices for the factors of production used by firms in the industry. When expansion of the industry does not affect the prices of factors of production, it is a constant-cost industry. In some cases, however, the entry of new firms may affect input prices.

As new firms enter, they add to the demand for the factors of production used by the industry. If the industry is a significant user of those factors, the increase in demand could push up the market price of factors of production for all firms in the industry. If that occurs, then entry into an industry will boost average costs at the same time as it puts downward pressure on price. Long-run equilibrium will still occur at a zero level of economic profit and with firms operating on the lowest point on the ATC curve, but that cost curve will be somewhat higher than before entry occurred. Suppose, for example, that an increase in demand for new houses drives prices higher and induces entry. That will increase the demand for workers in the construction industry and is likely to result in higher wages in the industry, driving up costs.

An industry in which the entry of new firms bids up the prices of factors of production and thus increases production costs is called an increasing-cost industry. As such an industry expands in the long run, its price will rise.

Some industries may experience reductions in input prices as they expand with the entry of new firms. That may occur because firms supplying the industry experience economies of scale as they increase production, thus driving input prices down. Expansion may also induce technological changes that lower input costs. That is clearly the case of the computer industry, which has enjoyed falling input costs as it has expanded. An industry in which production costs fall as firms enter in the long run is adecreasing-cost industry.

Just as industries may expand with the entry of new firms, they may contract with the exit of existing firms. In a constant-cost industry, exit will not affect the input prices of remaining firms. In an increasing-cost industry, exit will reduce the input prices of remaining firms. And, in a decreasing-cost industry, input prices may rise with the exit of existing firms.

The behavior of production costs as firms in an industry expand or reduce their output has important implications for the long-run industry supply curve, a curve that relates the price of a good or service to the quantity produced after all long-run adjustments to a price change have been completed. Every point on a long-run supply curve therefore shows a price and quantity supplied at which firms in the industry are earning zero economic profit. Unlike the short-run market supply curve, the long-run industry supply curve does not hold factor costs and the number of firms unchanged.

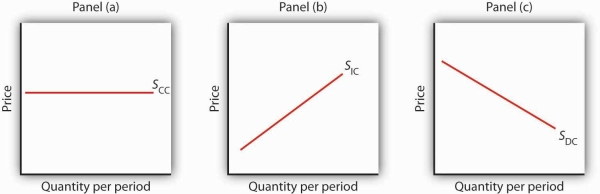

Figure 9.14 shows three long-run industry supply curves. In Panel (a), SCC is a long-run supply curve for a constant-cost industry. It is horizontal. Neither expansion nor contraction by itself affects market price. In Panel (b), SIC is a long-run supply curve for an increasing-cost industry. It rises as the industry expands. In Panel (c), SDC is a long-run supply curve for a decreasing-cost industry. Its downward slope suggests a falling price as the industry expands.

The long-run supply curve for a constant-cost, perfectly competitive industry is a horizontal line, SCC, shown in Panel (a). The long-run curve for an increasing-cost industry is an upward-sloping curve,SIC, as in Panel (b). The downward-sloping long-run supply curve, SDC, for a decreasing cost industry is given in Panel (c).

- 瀏覽次數:2560