In the model of perfect competition, we assume that a firm determines its output by finding the point where the marginal revenue and marginal cost curves intersect. Provided that price exceeds average variable cost, the firm produces the quantity determined by the intersection of the two curves.

A supply curve tells us the quantity that will be produced at each price, and that is what the firm’s marginal cost curve tells us. The firm’s supply curve in the short run is its marginal cost curve for prices above the average variable cost. At prices below average variable cost, the firm’s output drops to zero.

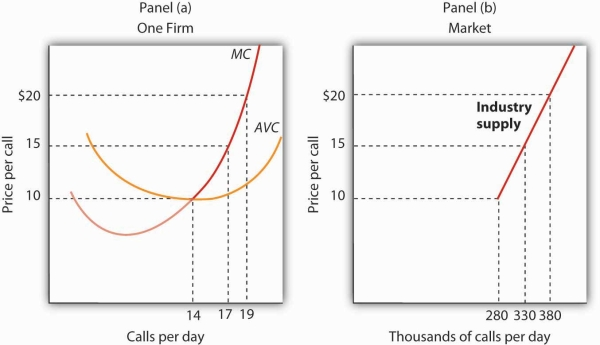

Panel (a) of Figure 9.9 shows the average variable cost and marginal cost curves for a hypothetical astrologer, Madame LaFarge, who is in the business of providing astrological consultations over the telephone. We shall assume that this industry is perfectly competitive. At any price below $10 per call, Madame LaFarge would shut down. If the price is $10 or greater, however, she produces an output at which price equals marginal cost. The marginal cost curve is thus her supply curve at all prices greater than $10.

The supply curve for a firm is that portion of its MC curve that lies above the AVC curve, shown in Panel (a). To obtain the short-run supply curve for the industry, we add the outputs of each firm at each price. The industry supply curve is given in Panel (b).

Now suppose that the astrological forecast industry consists of Madame LaFarge and thousands of other firms similar to hers. The market supply curve is found by adding the outputs of each firm at each price, as shown in Panel (b) of Figure 9.9. At a price of $10 per call, for example, Madame LaFarge supplies 14 calls per day. Adding the quantities supplied by all the other firms in the market, suppose we get a quantity supplied of 280,000. Notice that the market supply curve we have drawn is linear; throughout the book we have made the assumption that market demand and supply curves are linear in order to simplify our analysis.

Looking at Figure 9.9, we see that profit-maximizing choices by firms in a perfectly competitive market will generate a market supply curve that reflects marginal cost. Provided there are no external benefits or costs in producing a good or service, a perfectly competitive market satisfies the efficiency condition.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Price in a perfectly competitive industry is determined by the interaction of demand and supply.

- In a perfectly competitive industry, a firm’s total revenue curve is a straight, upward-sloping line whose slope is the market price. Economic profit is maximized at the output level at which the slopes of the total revenue and total cost curves are equal, provided that the firm is covering its variable cost.

- To use the marginal decision rule in profit maximization, the firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Economic profit per unit is price minus average total cost; total economic profit equals economic profit per unit times quantity.

- If price falls below average total cost, but remains above average variable cost, the firm will continue to operate in the short run, producing the quantity where MR = MC doing so minimizes its losses.

- If price falls below average variable cost, the firm will shut down in the short run, reducing output to zero. The lowest point on the average variable cost curve is called the shutdown point.

- The firm’s supply curve in the short run is its marginal cost curve for prices greater than the minimum average variable cost.

TRY IT!

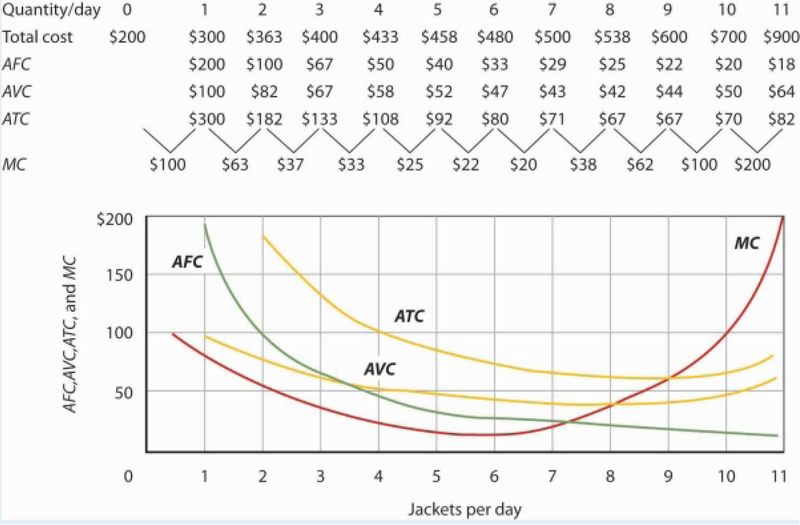

Assume that Acme Clothing, the firm introduced in the chapter on production and cost, produces jackets in a perfectly competitive market. Suppose the demand and supply curves for jackets intersect at a price of $81. Now, using the marginal cost and average total cost curves for Acme shown here:

Estimate Acme’s profit-maximizing output per day (assume the firm selects a whole number). What are Acme’s economic profits per day?

Case in Point: Not Out of Business ’Til They Fall from the Sky

The 66 satellites were poised to start falling from the sky. The hope was that the pieces would burn to bits on their way down through the atmosphere, but there was the chance that a building or a person would take a direct hit.

The satellites were the primary communication devices of Iridium’s satellite phone system. Begun in 1998 as the first truly global satellite system for mobile phones— providing communications across deserts, in the middle of oceans, and at the poles— Iridium expected five million subscribers to pay $7 a minute to talk on $3,000 handsets. In the climate of the late 1990s, users opted for cheaper, though less secure and less comprehensive, cell phones. By the end of the decade, Iridium had declared bankruptcy, shut down operations, and was just waiting for the satellites to start plunging from their orbits around 2007.

The only offer for Iridium’s $5 billion system came from an ex-CEO of a nuclear reactor business, Dan Colussy, and it was for a measly $25 million. “It’s like picking up a $150,000 Porsche 911 for $750,” wrote USA Today reporter, Kevin Maney.

The purchase turned into a bonanza. In the wake of September 11, 2001, and then the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, demand for secure communications in remote locations skyrocketed. New customers included the U.S. and British militaries, as well as reporters in Iraq, who, when traveling with the military have been barred from using less secure systems that are easier to track. The nonprofit organization Operation Call Home has bought time to allow members of the 81stArmor Brigade of the Washington National Guard to communicate with their families at home. Airlines and shipping lines have also signed up.

As the new Iridium became unburdened from the debt of the old one and technology improved, the lower fixed and variable costs have contributed to Iridium’s revival, but clearly a critical element in the turnaround has been increased demand. The launching of an additional seven spare satellites and other tinkering have extended the life of the system to at least 2014. The firm was temporarily shut down but, with its new owners and new demand for its services, has come roaring back.

Why did Colussy buy Iridium? A top executive in the new firm said that Colussy just found the elimination of the satellites a terrible waste. Perhaps he had some niche uses in mind, as even before September 11, 2001, he had begun to enroll some new customers, such as the Colombian national police, who no doubt found the system useful in the fighting drug lords. But it was in the aftermath of 9/11 that its subscriber list really began to grow and its re-opening was deemed a stroke of genius. Today Iridium’s customers include ships at sea (which account for about half of its business), airlines, military uses, and a variety of commercial and humanitarian applications.

Sources: Kevin Maney, “Remember Those ‘Iridium’s Going to Fail’ Jokes? Prepare to Eat Your Hat,” USA Today, April 9, 2003: p. 3B. Michael Mecham, “Handheld Comeback: A Resurrected Iridium Counts Aviation, Antiterrorism Among Its Growth Fields,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, 161: 9 (September 6, 2004): p. 58. Iridium’s webpage can be found at Iridium.com.

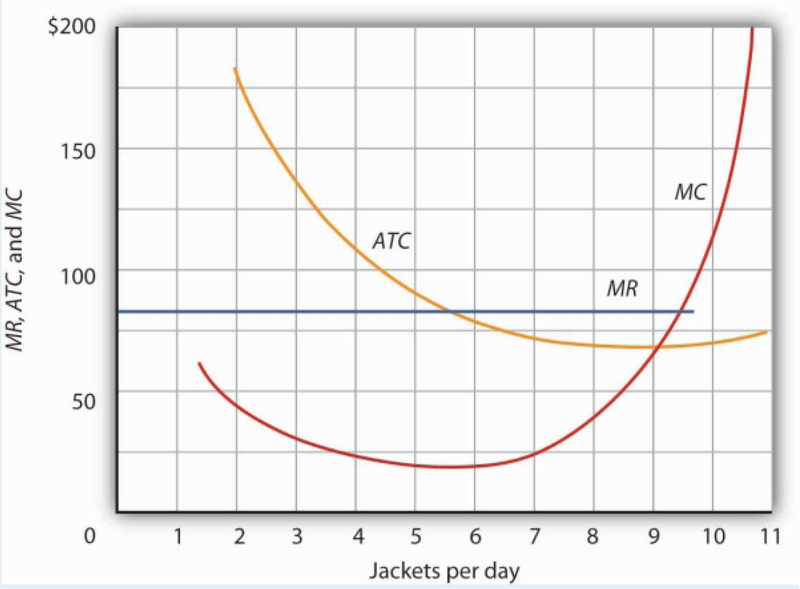

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

At a price of $81, Acme’s marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at $81. The firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue; the curves intersect at a quantity of 9 jackets per day. Acme’s average total cost at this level of output equals $67, for an economic profit per jacket of $14. Acme’s economic profit per day equals about $126.

- 瀏覽次數:80467