LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Define monopsony and differentiate it from monopoly.

- Apply the marginal decision rule to the profit-maximizing solution of a monopsony buyer.

- Discuss situations of monopsony in the real world.

We have seen that market power in product markets exists when firms have the ability to set the prices they charge, within the limits of the demand curve for their products. Depending on the factor supply curve, firms may also have some power to set prices they pay in factor markets.

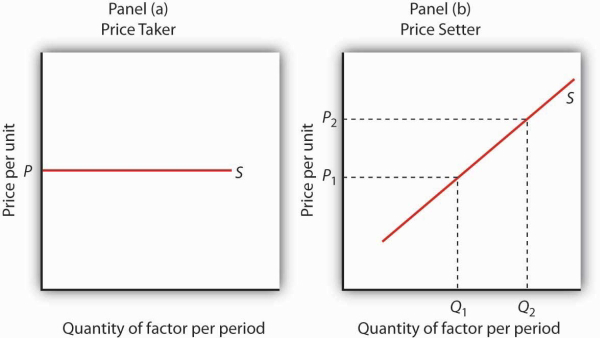

A firm can set price in a factor market if, instead of a market-determined price, it faces an upward-sloping supply curve for the factor. This creates a fundamental difference between price-taking and price-setting firms in factor markets. A price-taking firm can hire any amount of the factor at the market price; it faces a horizontal supply curve for the factor at the market-determined price, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 14.1. A price-setting firm faces an upward-sloping supply curve such as S in Panel (b). It obtains Q1 units of the factor when it sets the price P1. To obtain a larger quantity, such as Q2, it must offer a higher price, P2.

A price-taking firm faces the market-determined price P for the factor in Panel (a) and can purchase any quantity it wants at that price. A price-setting firm faces an upward-sloping supply curve S in Panel (b). The price-setting firm sets the price consistent with the quantity of the factor it wants to obtain. Here, the firm can obtain Q1 units at a price P1, but it must pay a higher price per unit, P2, to obtain Q2 units.

Consider a situation in which one firm is the only buyer of a particular factor. An example might be an isolated mining town where the mine is the single employer. A market in which there is only one buyer of a good, service, or factor of production is called a monopsony. Monopsony is the buyer’s counterpart of monopoly. Monopoly means a single seller; monopsony means a single buyer.

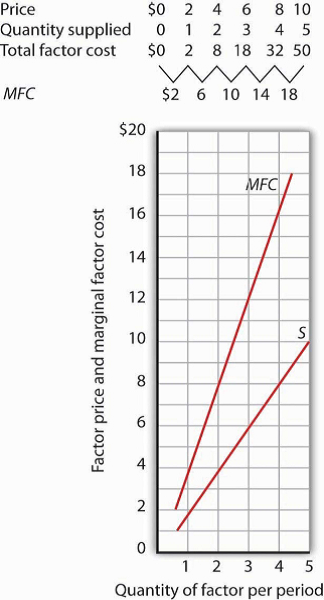

Assume that the suppliers of a factor in a monopsony market are price takers; there is perfect competition in factor supply. But a single firm constitutes the entire market for the factor. That means that the monopsony firm faces the upward-sloping market supply curve for the factor. Such a case is illustrated in Figure 14.2, where the price and quantity combinations on the supply curve for the factor are given in the table.

The table gives prices and quantities for the factor supply curve plotted in the graph. Notice that the marginal factor cost curve lies above the supply curve.

Suppose the monopsony firm is now using three units of the factor at a price of $6 per unit. Its total factor cost is $18. Suppose the firm is considering adding one more unit of the factor. Given the supply curve, the only way the firm can obtain four units of the factor rather than three is to offer a higher price of $8 for all four units of the factor. That would increase the firm’s total factor cost from $18 to $32. The marginal factor cost of the fourth unit of the factor is thus $14. It includes the $8 the firm pays for the fourth unit plus an additional $2 for each of the three units the firm was already using, since it has increased the prices for the factor to $8 from $6. The marginal factor cost (MFC) exceeds the price of the factor. We can plot the MFC for each increase in the quantity of the factor the firm uses; notice in Figure 14.2 that the MFC curve lies above the supply curve. As always in plotting in marginal values, we plot the $14 midway between units three and four because it is the increase in factor cost as the firm goes from three to four units.

- 3103 reads