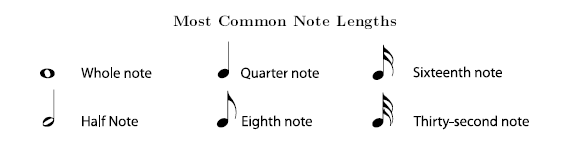

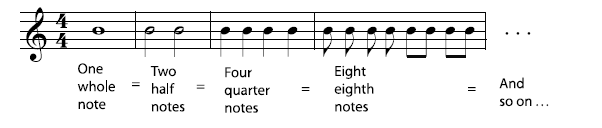

The simplest-looking note, with no stems or flags, is a whole note. All other note lengths are defined by how long they last compared to a whole note. A note that lasts half as long as a whole note is a half note. A note that lasts a quarter as long as a whole note is a quarter note. The pattern continues with eighth notes, sixteenth notes, thirty-second notes, sixty-fourth notes, and so on, each type of note being half the length of the previous type. (There is no such thing as third notes, sixth notes, tenth notes, etc.; see Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions to find out how notes of unusual lengths are written.)

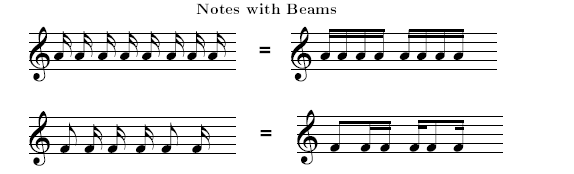

You may have noticed that some of the eighth notes in above Figure 1.36 don't have flags; instead they have a beam connecting them to another eighth note. If flagged notes are next to each other, their flags can be replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups. The beams may connect notes that are all in the same beat, or, in some vocal music, they may connect notes that are sung on the same text syllable. Each note will have the same number of beams as it would have flags.

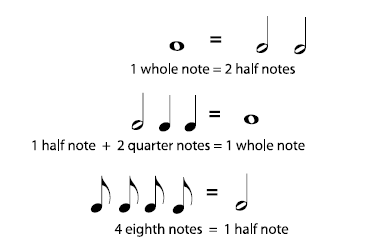

You may have also noticed that the note lengths sound like fractions in arithmetic. In fact they work very much like fractions: two half notes will be equal to (last as long as) one whole note; four eighth notes will be the same length as one half note; and so on. (For classroom activities relating music to fractions, see Fractions, Multiples, Beats, and Measures.)

Example

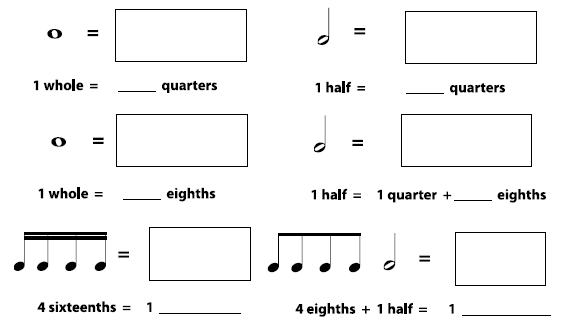

Exercise 1.8

Draw the missing notes and fill in the blanks to make each side the same duration length of time).

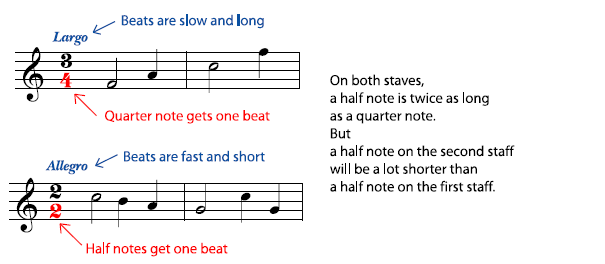

So how long does each of these notes actually last? That depends on a couple of things. A written note lasts for a certain amount of time measured in beats. To find out exactly how many beats it takes, you must know the time signature. And to find out how long a beat is, you need to know the tempo.

Example

- 12068 reads