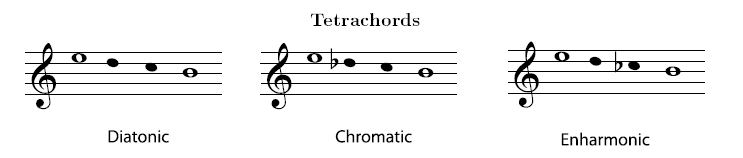

We can only guess what music from ancient Greek and Roman times really sounded like. They didn't leave any recordings, of course, nor did they write down their music. But they did write about music, so we know that they used modes based on tetrachords. A tetrachord is a mini-scale of four notes, in Pitch: Sharp, Flat, and Natural Notes order, that are contained within a Perfect Intervals (five half steps) instead of an octave (twelve half steps).

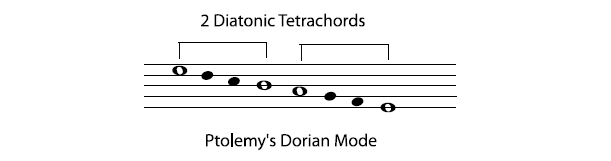

Since a tetrachord fills the interval of a perfect fourth, two tetrachords with a whole step between the end of one and the beginning of the other will fill an octave. Different Greek modes were built from different combinations of tetrachords.

We have very detailed descriptions of tetrachords and of Greek music theory (for example, Har- monics, written by Aristoxenus in the fourth century B.C.), but there is still no way of knowing exactly what the music really sounded like. The enharmonic, chromatic, and diatonic tetrachords mentioned in ancient descriptions are often now written as in the figure above. But references in the old texts to "shading" suggest that the reality was more complex, and that they probably did not use the same intervals we do. It is more likely that ancient Greek music sounded more like other traditional Mediterranean and Middle Eastern musics than that it sounded anything like modern Western music.

Westerncomposers often consistently choose minor keys over major keys (or vice versa) to convey certain moods (minor for melancholy, for example, and major for serene). One interesting aspect of Greek modes is that different modes were considered to have very different effects, not only on a person's mood, but even on character and morality. This may also be another clue that ancient modes may have had more variety of tuning and pitch than modern keys do.

- 5905 reads