The harmonic series is particularly important for brass instruments. A pianist or xylophone player only gets one note from each key. A string player who wants a different note from a string holds the string tightly in a different place. This basically makes a vibrating string of a new length, with a new fundamental.

But a brass player, without changing the length of the instrument, gets different notes by actually playing the harmonics of the instrument. Woodwinds also do this, although not as much. Most woodwinds can get two different octaves with essentially the same fingering; the lower octave is the fundamental of the column of air inside the instrument at that fingering. The upper octave is the first harmonic.

It is the brass instruments that excel in getting different notes from the same length of tubing.

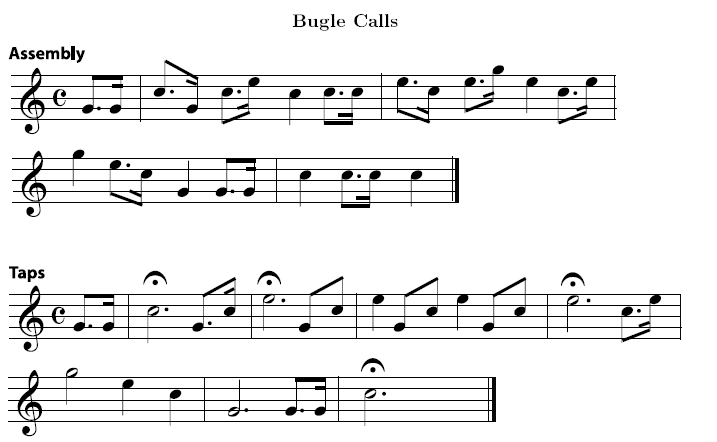

The sound of a brass instruments starts with vibrations of the player's lips. By vibrating the lips at different speeds, the player can cause a harmonic of the air column to sound instead of the fundamental. Thus a bugle player can play any note in the harmonic series of the instrument that falls within the player's range. Compare these well-known bugle calls to the harmonic series above.

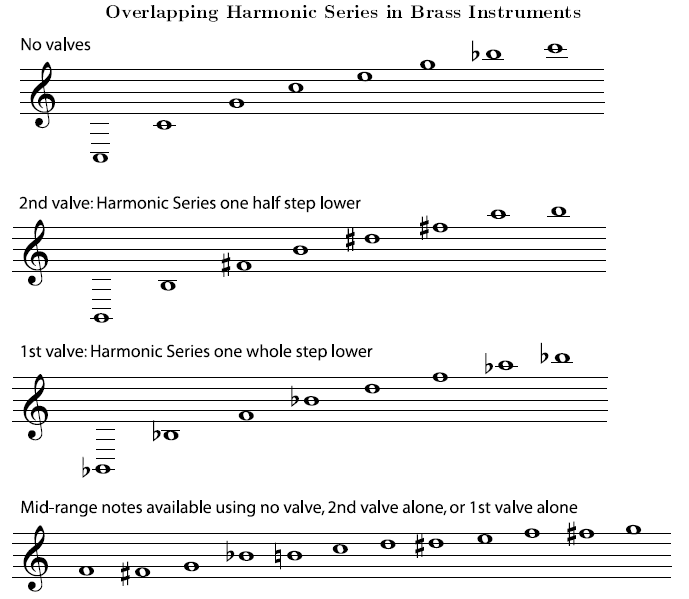

For centuries, all brass instruments were valveless. A brass instrument could play only the notes of one harmonic series. (An important exception was the trombone and its relatives, which can easily change their length and harmonic series using a slide.) The upper octaves of the series, where the notes are close enough together to play an interesting melody, were often difficult to play, and some of the harmonics sound quite out of tune to ears that expect equal temperament. The solution to these problems, once brass valves were perfected, was to add a few valves to the instrument; three is usually enough. Each valve opens an extra length of tube, making the instrument a little longer, and making available a whole new harmonic series. Usually one valve gives the harmonic series one half step lower than the valveless intrument; another, one whole step lower; and the third, one and a half steps lower. The valves can be used in combination, too, making even more harmonic series available. So a valved brass instrument can find, in the comfortable middle of its range (its middle register), a valve combination that will give a reasonably in-tune version for every note of the chromatic scale. (For more on the history of valved brass, see History of the French Horn. For more on how and why harmonics are produced in wind instruments, please see Standing Waves and Wind Instruments)

Exercise 4.17

Write the harmonic series for the instrument above when both the first and second valves are open. (You can use this PDF file if you need staff paper.) What new notes are added in the instrument's middle range? Are any notes still missing?

Note: The French horn has a reputation for being a "difficult" instrument to play. This is also because of the harmonic series. Most brass instruments play in the first few octaves of the harmonic series, where the notes are farther apart and it takes a pretty big difference in the mouth and lips (the embouchure, pronounced AHM-buh-sher) to get a different note. The range of the French horn is higher in the harmonic series, where the notes are closer together. So very small differences in the mouth and lips can mean the wrong harmonic comes out.

- 4575 reads