Most of the information that gets into sensory memory is forgotten, but information that we turn our attention to, with the goal of remembering it, may pass into short-term memory. Short-term memory (STM) is the place where small amounts of information can be temporarily kept for more than a few seconds but usually for less than one minute(Baddeley, Vallar, & Shallice,1990). 1 Information in short-term memory is not stored permanently but rather becomes available for us to process, and the processes that we use to make sense of,modify, interpret, and store information in STMare known as working memory.

Although it is called “memory,” working memory is not a store of memory like STM but rather a set of memory procedures or operations. Imagine, for instance, that you are asked to participate in a task such as this one, which is a measure of working memory (Unsworth & Engle, 2007). 2 Each of the following questions appears individually on a computer screen and then disappears after you answer the question:

|

Is 10 × 2 − 5 = 15? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “S” |

|

Is 12 ÷ 6 − 2 = 1? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “R” |

|

Is 10 × 2 = 5? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “P” |

|

Is 8 ÷ 2 − 1 = 1? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “T” |

|

Is 6 × 2 − 1 = 8? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “U” |

|

Is 2 × 3 − 3 = 0? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember “Q” |

To successfully accomplish the task, you have to answer each of the math problems correctly and at the same time remember the letter that follows the task. Then, after the six questions, you must list the letters that appeared in each of the trials in the correct order ( in this case S, R, P, T, U, Q).

To accomplish this difficult task you need to use a variety of skills. You clearly need to use STM, as you must keep the letters in storage until you are asked to list them. But you also need a way to make the best use of your available attention and processing. For instance, you might decide to use a strategy of “repeat the letters twice, then quickly solve the next problem, and then repeat the letters twice again including the new one.” Keeping this strategy (or others like it) going is the role of working memory’s central executive—the part of working memory that directs attention and processing. The central executive will make use of whatever strategies seem to be best for the given task. For instance, the central executive will direct the rehearsal process, and at the same time direct the visual cortex to form an image of the list of letters in memory. You can see that although STM is involved, the processes that we use to operate on the material in memory are also critical.

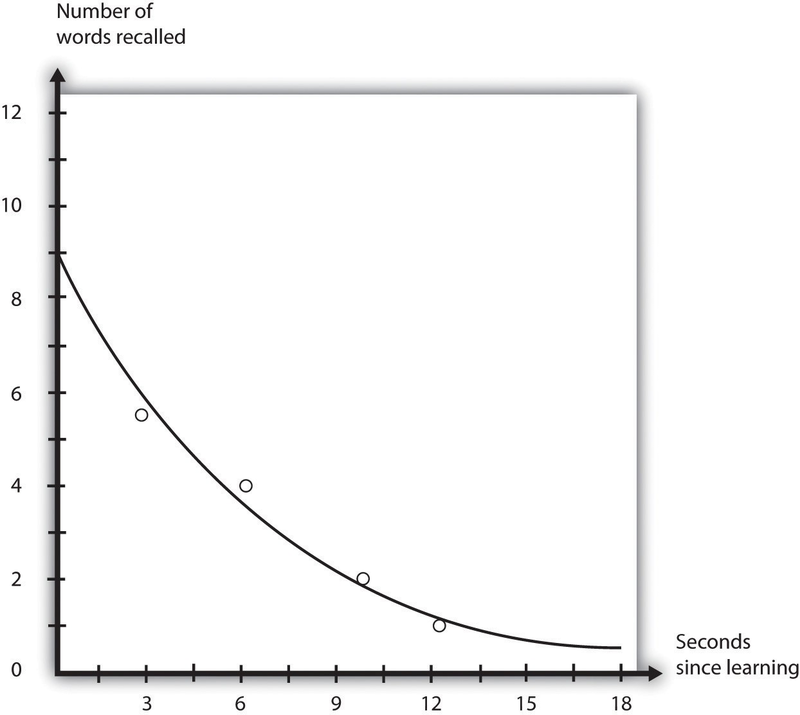

Short-term memory is limited in both the length and the amount of information it can hold. Peterson and Peterson (1959) 3 found that when people were asked to remember a list of three- letter strings and then were immediately asked to perform a distracting task (counting backward by threes), the material was quickly forgotten (see Figure 8.5), such that by 18 seconds it was virtually gone.

One way to prevent the decay of information from short-term memory is to use working memory to rehearse it. Maintenance rehearsal is the process of repeating information mentally or out loud with the goal of keeping it in memory. We engage in maintenance rehearsal to keep a something that we want to remember (e.g., a person’s name, e-mail address, or phone number) in mind long enough to write it down, use it, or potentially transfer it to long-term memory.

If we continue to rehearse information it will stay in STM until we stop rehearsing it, but there is also a capacity limit to STM. Try reading each of the following rows of numbers, one row at a time, at a rate of about one number each second. Then when you have finished each row, close your eyes and write down as many of the numbers as you can remember.

019

3586

10295

861059

1029384

75674834

657874104

6550423897

If you are like the average person, you will have found that on this test of working memory, known as a digit span test, you did pretty well up to about the fourth line, and then you started having trouble. I bet you missed some of the numbers in the last three rows, and did pretty poorly on the last one.

The digit span of most adults is between five a nd nine digits, with an average of about seven. The cognitive psychologist George Miller (1956) 4 referred to “seven plus or minus two” pieces of information as the “magic number” in short-term memory. But if we can only hold a maximum of about nine digits in short-term memory, then how can we remember larger amounts of information than this? For instance, how can we ever remember a 10-digit phone number long enough to dial it?

One way we are able to expand our ability to remember things in STM is by using a memory technique called chunking. Chunking is the process of organizing information into smaller groupings (chunks), thereby increasing the number of items that can beheld in STM. For instance, try to remember this string of 12 letters:

XOFCBANNCVTM

You probably won’t do that well because the number of letters is more than the magic number of seven.

Now try again with this one:

MTVCNNABCFOX

Would it help you if I pointed out that the material in this string could be chunked into four sets of three letters each? I think it would, because then rather than remembering 12 letters, you would only have to remember the names of four television stations. In this case, chunking changes the number of items you have to remember from 12 to only four.

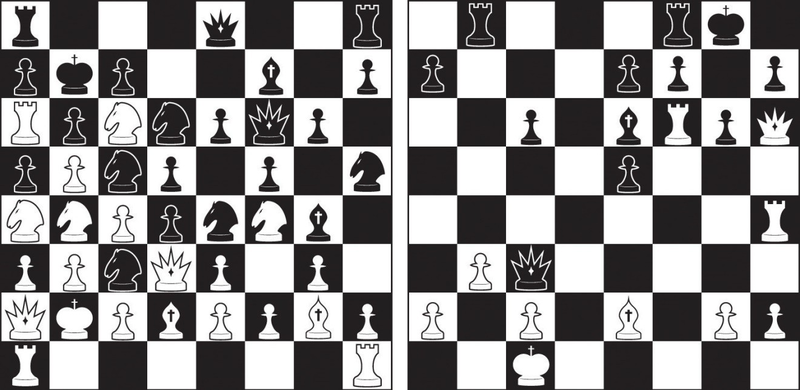

Experts rely on chunking to help them process complex information. Herbert Simon and William Chase (1973) 5 showed chess masters and chess novices various positions of pieces on a chessboard for a few seconds each. The experts did a lot better than the novices in remembering the positions because they were able to see the “big picture.” They didn’t have to remember the position of each of the pieces individually, but chunked the pieces into several larger layouts. But when the researchers showed both groups random chess positions—positions that would be very unlikely to occur in real games—both groups did equally poorly, because in this situation the experts lost their ability to organize the layouts (see Figure 8.6). The same occurs for basketball. Basketball players recall actual basketball positions much better than do nonplayers, but only when the positions make sense in terms of what is happening on the court, or what is likely to happen in the near future, and thus can be chunked into bigger units (Didierjean & Marmèche, 2005). 6

If information makes it past short term-memory it may enter long-term memory (LTM), memory storage that can hold information for days, months, and years. The capacity of long-term memory is large, and there is no known limit to what we can remember (Wang, Liu, & Wang, 2003). 7Although we may forget at least some information after we learn it, other things will stay with us forever. In the next section we will discuss the principles of long-term memory.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Memory refers to the ability to store and retrieve information over time.

- For some things our memory is very good, but our active cognitive processing of information assures that memory is never an exact replica of what we have experienced.

- Explicit memory refers to experiences that can be intentionally and consciously remembered, and it is measured using recall, recognition, and relearning. Explicit memory includes episodic and semantic memories.

- Measures of relearning (also known as savings) assess how much more quickly information is learned when it is studied again after it has already been learned but then forgotten.

- Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. The three types of implicit memory are procedural memory, classical conditioning, and priming.

- Information processing begins in sensory memory, moves to short-term memory, and eventually moves to long-term memory.

- Maintenance rehearsal and chunking are used to keep information in short-term memory.

- The capacity of long-term memory is large, and there is no known limit to what we can remember.

EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- List some situations in which sensory memory is useful for you. What do you think your experience of the stimuli would be like if you had no sensory memory?

- Describe a situation in which you need to use working memory to perform a task or solve a problem. How do your working memory skills help you?

- 5269 reads