Freud proposed that the mind is divided into three components: id, ego, and superego, and that the interactions and conflicts among the components create personality (Freud, 1923/1943). 1 According to Freudian theory, the id is the component of personality that forms the basis of our most primitive impulses. The id is entirely unconscious, and it drives our most important motivations, including the sexual drive (libido) and the aggressive or destructive drive (Thanatos). According to Freud, the id is driven by the pleasureprinciple—the desire for immediate gratification of our sexual and aggressive urges. The id is why we smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, view pornography, tell mean jokes about people, and engage in other fun or harmful behaviors, often at the cost of doing more productive activities.

In stark contrast to the id, the superego represents our senseof moralityand oughts. The superego tell us all the things that we shouldn’t do, or the duties and obligations of society. The superego strives for perfection, and when we fa il to live up to its demands we feel guilty.

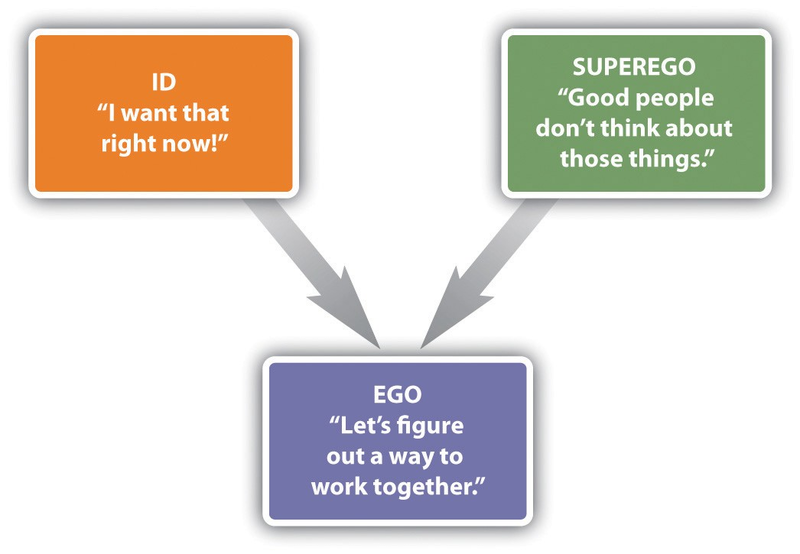

In contrast to the id, which is about the pleasure principle, the function of theegois based on the reality principle—the idea that we must delay gratification of our basic motivations until the appropriate time with the appropriate outlet. The ego is the largely conscious controller or decision-maker of personality. The ego serves as the intermediary between the desires of the id and the constraints of society contained in the superego (Figure 11.6). We may wish to scream, yell, or hit, and yet our ego normally tells us to wait, reflect, and choose a more appropriate response.

Freud believed that psychological disorders, and particularly the experience of anxiety, occur when there is conflict or imbalance among the motivations of the id, ego, and superego. When the ego finds that the id is pressing too hard for immediate pleasure, it attempts to correct for this problem, often through the use of defense mechanisms—unconscious psychological strategies used to copewith anxiety and to maintain a positiveself-image. Freud believed that the defense mechanisms were essential for effective coping with everyday life, but that any of them could be overused (Table 11.4).

|

Defense mechanism |

Definition |

Possible behavioral example |

|

Displacement |

Diverting threatening impulses away from the source of the anxiety and toward a more acceptable source |

A student who is angry at her professor for a low grade lashes out at her roommate, who is a safer target of her anger. |

|

Projection |

Disguising threatening impulses by attributing them to others |

A man with powerful unconscious sexual desires for women claims that women use him as a sex object. |

|

Rationalization |

Generating self-justifying explanations for our negative behaviors |

A drama student convinces herself that getting the part in the play wasn’t that important after all. |

|

Reaction formation |

Making unacceptable motivations appear as their exact opposite |

Jane is sexually attracted to friend Jake, but she claims in public that she intensely dislikes him. |

|

Regression |

Retreating to an earlier, more childlike, and safer stage of development |

A college student who is worried about an important test begins to suck on his finger. |

|

Repression (or denial) |

Pushing anxiety-arousing thoughts into the unconscious |

A person who witnesses his parents having sex is later unable to remember anything about the event. |

|

Sublimation |

Channeling unacceptable sexual or aggressive desires into acceptable activities |

A person participates in sports to sublimate aggressive drives. A person creates music or art to sublimate sexual drives. |

The most controversial, and least scientifically valid, part of Freudian theory is its explanations of personality development. Freud argued that personality is developed through a series of psychosexual stages, each focusing on pleasure from a different part of the body (Table 11.5). Freud believed that sexuality begins in infancy, and that the appropriate resolution of each stage has implications for later personality development.

|

Stage |

Approximate ages |

Description |

|

|

Oral |

Birth to 18 months |

Pleasure comes from the mouth in the form of sucking, biting, and chewing. |

|

|

Anal |

18 months to 3 years |

Pleasure comes from bowel and bladder elimination and the constraints of toilet training. |

|

|

Phallic |

3 years to 6 years |

Pleasure comes from the genitals, and the conflict is with sexual desires for the opposite- sex parent. |

|

|

Latency |

6 years to puberty |

Sexual feelings are less important. |

|

|

Genital |

Puberty and older |

If prior stages have been properly reached, mature sexual orientation develops. |

|

In the first of Freud’s proposed stages of psychosexual development, which begins at birth and lasts until about 18 months of age, the focus is on the mouth. During this oral stage, the infant obtains sexual pleasure by sucking and drinking. Infants who receive either too little or too much gratification become fixated or “locked” in the oral stage, and are likely to regress to these points of fixation under stress, even as adults. According to Freud, a c hild who receives too little oral gratification (e.g., who was underfed or neglected) will become orally dependent as an adult and be likely to manipulate others to fulfill his or her needs rather than becoming independent. On the other hand, the child who was overfed or overly gratified will resist growing up and try to return to the prior state of dependency by acting helpless, demanding satisfaction from others, and acting in a needy way.

The anal stage, lasting from about 18 months to 3 years of age is when children first experience psychological conflict. During this stage children desire to experience pleasure through bowel movements, but they are also being toilet trained to delay this gratification. Freud believed that if this toilet training was either too harsh or too lenient, children would become fixated in the anal stage and become likely to regress to this stage under stress as adults. If the child received too little anal gratification (i.e., if the parents had been very harsh about toilet training), the adult personality will be anal retentive—stingy, with a compulsive seeking of order and tidiness. On the other hand, if the parents had been too lenient, the anal expulsive personality results, characterized by a lack of self-control and a tendency toward messiness and carelessness.

The phallicstage, which lasts from age 3 to age 6 is when the penis (for boys) and clitoris (for girls) become the primary erogenous zone for sexual pleasure. During this stage, Freud believed that children develop a powerful but unconscious attraction for the opposite-sex parent, as well as a desire to eliminate the same-sex parent as a rival. Freud based his theory of sexual development in boys (the “Oedipus complex”) on the Greek mythological character Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother, and then put his own eyes out when he learned what he had done. Freud argued that boys will normally eventually abandon their love of the mother, and instead identify with the father, also taking on the father’s personality characteristics, but that boys who do not successfully resolve the Oedipus complex will experience psychological problems later in life. Although it was not as important in Freud’s theorizing, in girls the phallic stage is often termed the “Electra complex,” after the Greek character who avenged her father’s murder by killing her mother. Freud believed that girls frequently experienced penisenvy, the sense of deprivation supposedly experienced by girls because they do not have a penis.

The latency stageis a period of relative calm that lasts from about 6 years to 12 years. During this time, Freud believed that sexual impulses were repressed, leading boys and girls to have little or no interest in members of the opposite sex.

The fifth and last stage, the genital stage, begins about 12 years of age and lasts into adulthood. According to Freud, sexual impulses return during this time frame, and if development has proceeded normally to this point, the c hild is able to move into the development of mature romantic relationships. But if earlier problems have not been appropriately resolved, difficulties with establishing intimate love attachments are likely.

Freud’s Followers: The Neo-Freudians

Freudian theory was so popular that it led to a number of followers, including many of Freud’s own students, who developed, modified, and expanded his theories. Taken together, these approaches are known as neo-Freudian theories. The neo-Freudian theories are theories based on Freudian principles that emphasize the role of the unconscious and early experience in shaping personality but place less evidence on sexuality as the primary motivating force in personality and are more optimistic concerning the prospects for personality growth and change in personalityin adults.

Alfred Adler (1870–1937) was a follower of Freud who developed his own interpretation of Freudian theory. Adler proposed that the primary motivation in human personality was not sex or aggression, but rather the striving for superiority. According to Adler, we desire to be better than others and we accomplish this goal by creating a unique and valuable life. We may attempt to satisfy our need for superiority through our school or professional accomplishments, or by our enjoyment of music, athletics, or other activities that seem important to us.

Adler believed that psychological disorders begin in early childhood. He argued that children who are either overly nurtured or overly neglected by their parents are later likely to develop an inferiority complex—a psychological state in which people feel that they are not living up to expectations, leading them to have low self-esteem, with a tendency to try to overcompensate for the negative feelings. People with an inferiority complex often attempt to demonstrate their superiority to others at all costs, even if it means humiliating, dominating, or alienating them. According to Adler, most psychological disorders result from misguided attempts to compensate for the inferiority complex in order meet the goal of superiority.

Carl Jung (1875–1961) was another student of Freud who developed his own theories about personality. Jung agreed with Freud about the power of the unconscious but felt that Freud overemphasized the importance of sexuality. Jung argued that in addition to the personal unconscious, there was also acollective unconscious, or a collection of shared ancestral memories. Jung believed that the collective unconscious contains a variety of archetypes, or cross-culturally universal symbols, which explain the similarities among people in their emotional reactions to many stimuli. Important archetypes include the mother, the goddess, the hero, and the mandala or circle, which Jung believed symbolized a desire for wholeness or unity. For Jung, the underlying motivation that guides successful personality is self-realization, or learning about and developing the self to the fullest possible extent.

Karen Horney (the last syllable of her last name rhymes with “eye”; 1855–1952), was a German physician who applied Freudian theories to create a personality theory that she thought was more balanced between men and women. Horney believed that parts of Freudian theory, and particularly the ideas of the Oedipus complex and penis envy, were biased against women. Horney argued that women’s sense of inferiority was not due to their lack of a penis but rather to their dependency on men, an approach that the culture made it difficult for them to break from. For Horney, the underlying motivation that guides personality development is the desire for security, the ability to develop appropriate and supportive relationships with others.

Another important neo-Freudian was Erich Fromm (1900–1980). Fromm’s focus was on the negative impact of technology, arguing that the increases in its use have led people to feel increasingly isolated from others. Fromm believed that the independence that technology brings us also creates the need “escape from freedom,” that is, to become closer to others.

Research Focus: How the Fear of Death Causes Aggressive Behavior

Fromm believed that the primary human motivation was to escape the fe ar of death, and contemporary research has shown how o ur concerns about dying can influence our behavior. In this research, people have been made to confront their death by writing about it or otherwise being reminded of it, and effects on their behavior are then observed. In one relevant study, McGregor et al. (1998) 2demonstrated that people who are provoked may be particularly aggressive after they have been reminded of the possibility of their own death. The participants in the study had been selected, on the basis of prior reporting, to have either politically liberal or politically conservative views. When they arrived at the lab they were asked to write a short paragraph describing their opinion of politics in the United States.

In addition, half of the participants (the mortality salient condition) were asked to “briefly describe the emotions that the thought of your own death arouses in you” and to “jot down as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you as you physically die, and once you are physically dead.” Participants in the exam control condition also thought about a negative event, but not one associated with a fear of death. They were instructed to “please briefly describe the emotions that the thought of your next important exam arouses in you” and to “jot down as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you as you physically take your next exam, and once you are physically taking your next exam.”

Then the participants read the essay that had supposedly just been written by another person. (The other person did not exist, but the participants didn’t know this until the end of the experiment.) The essay that they read had been prepared by the experimenters to be ve ry negative toward politically liberal views or to be very negative toward politically conservative views. Thus one-half of the participants were provoked by the other person by reading a statement that strongly conflicted with their own political beliefs, whereas the other half read an ess ay in which the other person’s views supported their own (liberal o r conservative) beliefs.

At this point the participants moved on to what they thought was a completely separate study in which they were to be tasting and giving their impression of some foods. Furthermore, they were told that it was necessary for the participants in the research to administer the food samples to each other. At this point, the participants found out that the food they were going to be sampling was spicy hot sauce and that they were going to be administering the sauce to the very person whose essay they had just read. In addition, the participants read some information about the other person that indicated that he very much disliked eating spicy food. Participants were given a taste of the hot sauce (it was really hot!) and then instructed to place a quantity of it into a cup for the other person to sample. Furthermore, they were told that the other person would have to e at all the sauce.

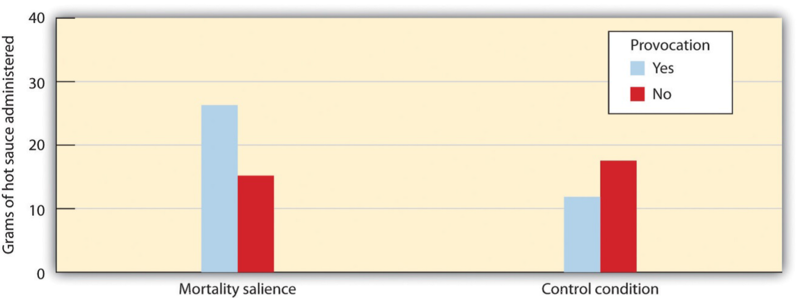

As you can see in "Aggression as a Function of Mortality Salience and Provocation[Missing]", McGregor et al. found that the participants who had not been reminded of their own death, even if they had been insulted by the partner, did not retaliate by giving him a lot of hot sauce to eat. On the other hand, the participants who were both provoked by the other person and who had also been reminded of their own death administered significantly more hot sauce than did the participants in the other three conditions. McGregor et al. (1998) argued that thinking about one’s own death creates a strong concern with maintaining one’s one cherished worldviews (in this case our political beliefs). When we are concerned about dying we become more motivated to defend these important beliefs from the challenges made by others, in this case by aggressing through the hot sauce.

- 26736 reads