Psychoanalytic models of personality were complemented during the 1950s and 1960s by the theories of humanistic psychologists. In contrast to the proponents of psychoanalysis, humanists embraced the notion of free will. Arguing that people ar e free to choose their own lives and make their own decisions, humanistic psychologists focused on the underlying motivations that they believed drove personality, focusing on the nature of the self-concept,theset of beliefs about who weare, and self-esteem, our positive feelings about the self.

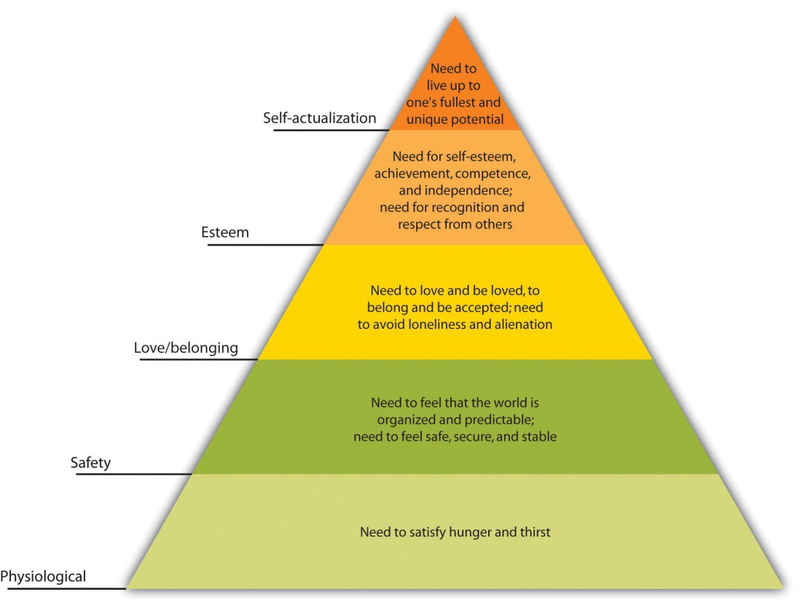

One of the most important humanists, Abraham Maslow (1908–1970), conceptualized personality in terms of a pyramid-shaped hierarchyof motivesFigure 11.8. At the base of the pyramid are the lowest-level motivations, including hunger and thirst, and safety and belongingness. Maslow argued that only when people are able to meet the lower-level needs are they able to move on to achieve the higher-level needs of self- esteem, and eventually self-actualization, which is the motivation to develop our innate potential to the fullest possible extent.

Maslow studied how successful people, including Albert Einstein, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Helen Keller, and Mahatma Gandhi had been able to lead such successful and productive lives. Maslow (1970) 1 believed that self-actualized people are creative, spontaneous, and loving of themselves and others. They tend to have a few deep friendships rather than many superficial ones, and are generally private. He felt that these individuals do not need to conform to the opinions of others because they are very confident and thus free to express unpopular opinions. Self-actualized people ar e also likely to have peak experiences, or transcendent moments of tranquility accompanied by a strong sense of connection with others.

Perhaps the best-known humanistic theorist is Carl Rogers (1902–1987). Rogers was positive about human nature, viewing people as primarily moral and helpful to others, and believed that we can achieve our f ull potential for emotional fulfillment if the self-concept is characterized byunconditional positive regard—a set of behaviors including being genuine, open toexperience, transparent,ableto listen to others, and self-disclosing and empathic. When we treat ourselves or others with unconditional positive regard, we express understanding and support, even while we may acknowledge failings. Unconditional positive regard allows us to admit our fears and failures, to drop our pretenses, and yet at the same time to feel completely accepted for what we are. The principle of unconditional positive regard has become a foundation of psychological therapy; therapists who use it in their practice are more effective than those who do not (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007; Yalom, 1995). 2

Although there are critiques of the humanistic psychologists (e.g., that Maslow focused on historically productive rather than destructive personalities in his research and thus drew overly optimistic conclusions about the capacity of people to do good), the ideas of humanism are so powerful and optimistic that they have continued to influence both everyday experiences as well as psychology. Today the positivepsychologymovement argues for many of these ideas, and research has documented the extent to which thinking positively and openly has important positive consequences for our relationships, our life satisfaction, and our psychological and physical health (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). 3

Research Focus: Self-Discrepancies, Anxiety, and Depression

Tory Higgins and his colleagues (Higgins, Bond, Klein, &

Strauman, 1986; Strauman & Higgins, 1988) 4 have studied how different aspects of the self-concept relate to personality characteristics. These researchers focused on

the types of emotional distress that we might experience as a result of how we are currently evaluating our self- concept. Higgins proposes that the emotions we experience are determined both

by our perceptions of how well our own behaviors meet up to the standards and goals we have provided ourselves (our internal standards) and by our perceptions of how others think about us

(our external standards). Furthermore, Higgins argues that different types of self-discrepancies lead to different types of negative emotions.

In one of Higgins’s experiments (Higgins, Bond, Klein, &

Strauman., 1986), 5 participants were first asked to describe themselves using a self-report measure. The participants listed 10 thoughts that

they thought described the kind of person they actually are; this is the actualself-concept. Then, participants also listed 10 thoughts that they thought described the

type of person they would “ideally like to be” (the idealself-concept) as well as 10 thoughts describing the w ay that someone else—for instance, a

parent—thinks they “ought to be” (the ought self-concept). Higgins then divided his participants into two groups. Those

with low self-concept discrepancies were those who listed similar traits on all three lists. Their ideal,

ought, and actual self-concepts were all pretty similar and so they were no t considered to be vulnerable to threats to their self-concept. The other half of the participants, those

with high self-concept discrepancies, were those for whom the traits listed on the ideal and ought lists were very

different from those listed on the actual self list. These participants were expected to be vulnerable to threats to the self-concept.

Then, at a later research session, Higgins first asked people to

express their current emotions, including those related to sadness and anxiety. After obtaining this baseline measure Higgins activated either ideal or ought discrepancies for the

participants. Participants in the ideal self-discrepancy priming condition were asked to think about and discuss their own and their

parents’ hopes and goals for them. Participants in the oughtself-priming conditionlisted their own and their parents’ beliefs concerning their duty and

obligations. Then all participants again indicated their current emotions.

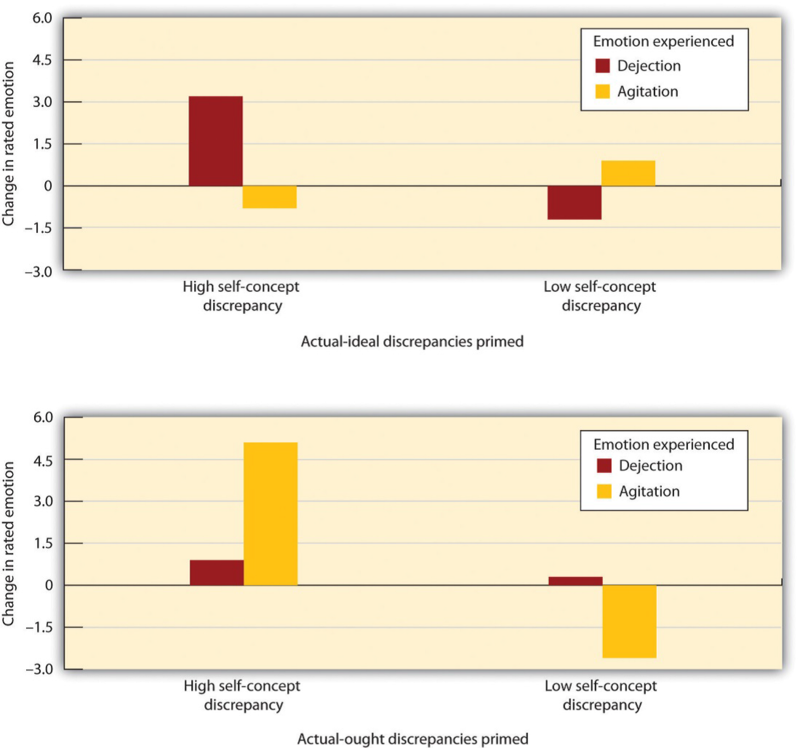

As you can see in Figure 11.9, for low self-concept discrepancy participants,

thinking about their ideal or ought selves did not much change their emotions. For high self-concept discrepancy participants, however, priming the ideal self-concept increased their sadness

and dejection, whereas priming the ought self-concept increased their anxiety and agitation. These results are consistent with the idea that discrepancies between the ideal and the actual

self lead us to experience sadness, dissatisfaction, and other depression-related emotions, whereas discrepancies between the actual and ought self are more likely to lead to fear, worry,

tension, and other anxiety-related emotions.

One of the critical aspects of Higgins’s approach is that, as is our personality, our feelings are also influenced both by our own behavior and by our expectations of how other people view us. This makes it clear that even though you might not care that much about achieving in school, your failure to do well may still produce negative emotions because you realize that your parents do think it is important.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- One of the most important psychological approaches to understanding personality is based on the psychodynamic approach to personality developed by Sigmund Freud.

- For Freud the mind was like an iceberg, with the many motivations of the unconscious being much larger, but also out of sight, in comparison to the consciousness of which we are aware.

- Freud proposed that the mind is divided into three components: id, ego, and superego, and that the interactions and conflicts among the components create personality.

- Freud proposed that we use defense mechanisms to cope with anxiety and to maintain a positive self-image.

- Freud argued that personality is developed through a series of psychosexual stages, each focusing on pleasure from a different part of the body.

- The neo-Freudian theorists, including Adler, Jung, Horney, and Fromm, emphasized the role of the unconscious and early experience in shaping personality, but placed less evidence on sexuality as the primary motivating force in personality.

- Psychoanalytic and behavioral models of personality were complemented during the 1950s and 1960s by the theories of humanistic psychologists, including Maslow and Rogers.

EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Based on your understanding of psychodynamic theories, how would you analyze your own personality? Are there aspects of the theory that might help you explain your own strengths and weaknesses?

- Based on your understanding of humanistic theories, how would you try to change your behavior to better meet the underlying motivations of security, acceptance, and self-realization?

- Consider your own self-concept discrepancies. Do you have an actual-ideal or actual-ought discrepancy? Which one is more important for you, and why?

- 16154 reads