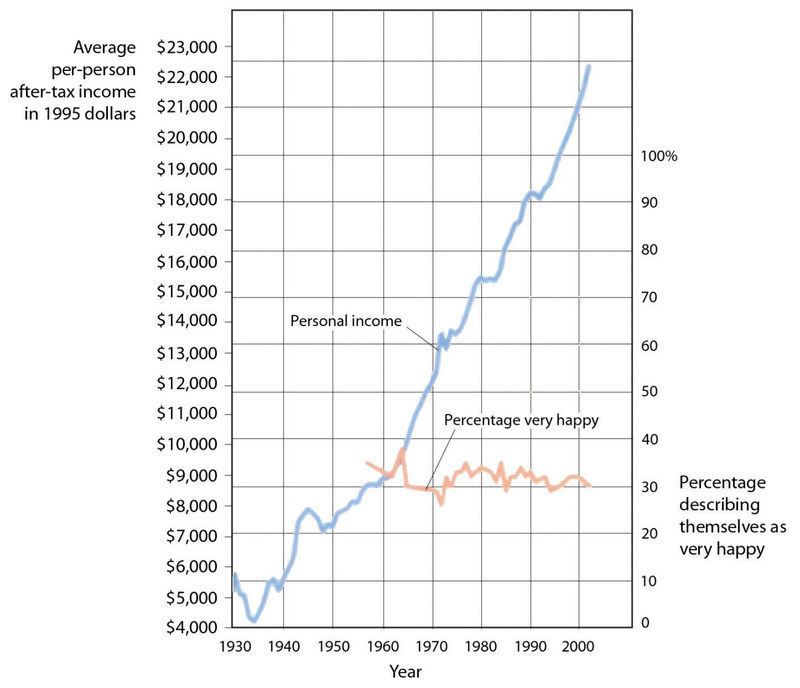

One difficulty that people face when trying to improve their happiness is that they may not always know what will make them happy. As one example, many of us think that if we just had more money we would be happier. While it is true that we do need money to afford food and adequate shelter for ourselves and our families, after this minimum level of wealth is reached, more money does not generally buy more happiness (Easterlin, 2005). 1 For instance, as you can see in , even though income and material success has improved dramatically in many countries over the past decades, happiness has not. Despite tremendous economic growth in France, Japan, and the United States between 1946 to 1990, there was no increase in reports of well-being by the citizens of these countries. Americans today have a bout three times the buying power they had in the 1950s, and yet overall happiness has not increased. The problem seems to be that we never seem to have enough money to make us “really” happy. Csikszentmihalyi (1999) 2 reported that people who earned $30,000 per year felt that they would be happier if they made $50,000 per year, but that people who earned $100,000 per year said that they would need $250,000 per year to make them happy.

These findings might lead us to conclude that we don’t always know what does or what might make us happy, and this seems to be at least partially true. For instance, Jean Twenge and her colleagues (Twenge, Campbell & Foster, 2003) 3 have found in several studies that although people with children frequently claim that having children makes them happy, couples who do not have children actually report being happier than those who do.

Psychologists have found that people’s ability to predict their future emotional states is not very accurate (Wilson & Gilbert, 2005). 4 For one, people overestimate their emotional reactions to events. Although people think that positive and negative events that might occur to them will make a huge difference in their lives, and although these changes do make at least some difference in life satisfaction, they tend to be less influential than we think they are going to be. Positive events tend to make us feel good, but their effects wear off pretty quickly, and the same is true for negative events. For instance, Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman (1978) 5interviewed people who had won more than $50,000 in a lottery and found that they were not happier than they had been in the past, and were also not happier than a control group of similar people who had not won the lottery. On the other hand, the researchers found that individuals who were paralyzed as a result of accidents were not as unhappy as might be expected.

How can this possibly be? There are several reasons. For one, people are resilient; they bring their coping skills to play when negative events occur, and this makes them feel better. Secondly, most people do not continually experience very positive, or very negative, affect over a long period of time, but rather adapt to their current circumstances. Just as we enjoy the second chocolate bar we eat less than we enjoy the first, as we experience more and more positive outcomes in our daily lives we habituate to them and our life satisfaction returns to a more moderate level (Small, Zatorre, Dagher, Evans, & Jones-Gotman, 2001). 6

Another reason that we may mispredict our happiness is that our social comparisons change when our own status changes as a result of new events. People who are wealthy compare themselves to other wealthy people, people who are poor tend to compare with other poor people, and people who are ill tend to compare with other ill people, When our comparisons change, our happiness levels are correspondingly influenced. And when people are asked to predict their future emotions, they may focus only on the positive or negative event they are asked about, and forget about all the other things that won’t change. Wilson, Wheatley, Meyers, Gilbert, and Axsom (2000) 7 found that when people were asked to focus on all the more regular things that they will still be doing in the future (working, going to church, socializing with family and friends, and so forth), their predictions about how something really good or bad would influence them were less extreme.

If pleasure is fleeting, at least misery shares some of the same quality. We might think we can’t be happy if something terrible, such as the loss of a partner or child, were to happen to us, but after a period of adjustment most people find that happiness levels return to prior levels (Bonnano et al., 2002). 8Health concerns tend to put a damper on our feeling of well-being, and those with a serious disability or illness show slightly lowered mood levels. But even when health is compromised, levels of misery are lower than most people expect (Lucas, 2007; Riis et al., 2005). 9 For instance, although disabled individuals have more concern about health, safety, and acceptance in the community, they still experience overall positive happiness levels (Marinić & Brkljačić, 2008). 10 Taken together, it has been estimated that our wealth, health, and life circumstances account for only 15% to 20% of life satisfaction scores (Argyle,1999). 11 Clearly the main ingredient in happiness lies beyond, or perhaps beneath, external factors.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Positive thinking can be beneficial to our health.

- Optimism, self-efficacy, and hardiness all relate to positive health outcomes.

- Happiness is determined in part by genetic factors, but also by the experience of social support.

- People may not always know what will make them happy.

- Material wealth plays only a small role in determining happiness.

EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Are you a happy person? Can you think of ways to increase your positive emotions?

- Do you know what will make you happy? Do you believe that material wealth is not as important as you might have thought it would be?

- 3641 reads