Asch’s Line Matching Studies

Watch this video to see a demonstration of Asch’s line studies.

The tendency to conform to thosein authority, known as obedience, was demonstrated in a remarkable set of studies performed by Stanley Milgram (1974). 1 Milgram designed a study in which he could observe the extent to which a person who presented himself a s an authority would be able to produce obedience, even to the extent of leading people to cause harm to others. Like many other researchers who were interested in conformity, Milgram’s interest stemmed in part from his desire to understand how the presence of a powerful social situation—in this case the directives of Adolph Hitler, the German dictator who ordered the killing of millions of Jews and other “undesirable” people during World War II—could produce obedience.

Milgram used newspaper ads to recruit men (and in one study, women) from a wide variety of backgrounds to participate in his research. When the research participant arrived at the lab, he or she was introduced to a man who was ostensibly another research participant but who actually was a confederate working with the experimenter as part of the experimental team. The experimenter explained that the goal of the research was to study the effects of punishment on learning. After the participant and the confederate both consented to be in the study, the researcher explained that one of them would be the teacher, and the other the learner. They were each given a slip of paper a nd asked to open it and indicate what it said. In fact both papers read “teacher,” which allowed the confederate to pretend that he had been assigned to be the learner and thus to assure that the actual participant was always the teacher.

While the research participant (now the teacher) looked on, the learner was taken into the adjoining shock room and strapped to an electrode that was to deliver the punishment. The experimenter explained that the teacher’s job would be to sit in the control room and read a list of word pairs to the learner. After the teacher read the list once, it would be the learner’s job to remember which words went together. For instance, if the word pair was “blue sofa,” the teacher would say the word “blue” on the testing trials, and the learner would have to indicate which of four possible words (“house,” “sofa,” “cat,” or “carpet”) was the correct answer by pressing one of four buttons in front of him.

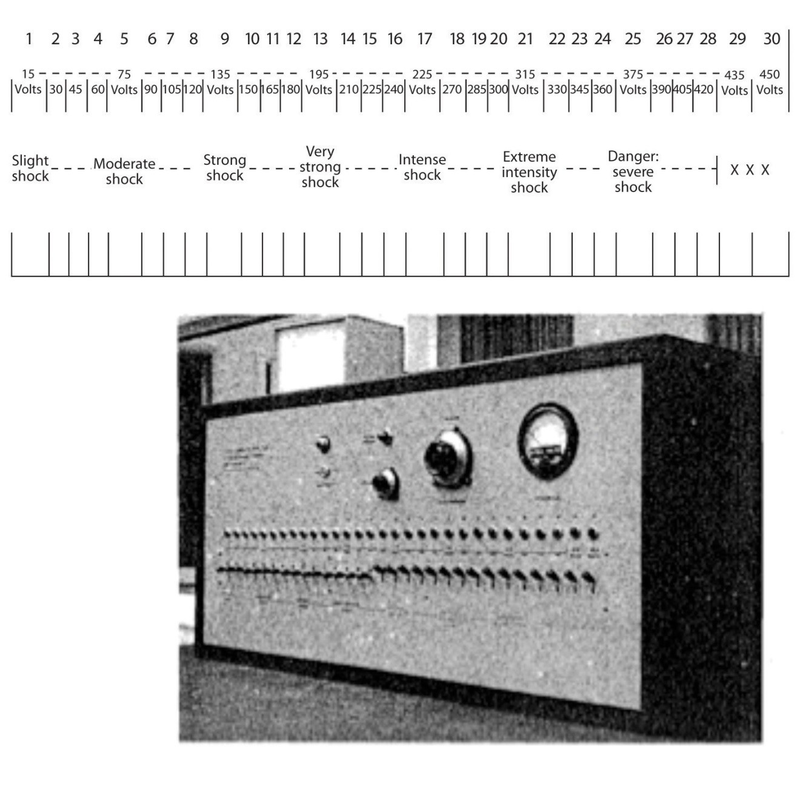

After the experimenter gave the “teacher” a mild shock to demonstrate that the shocks really were painful, the experiment began. The research participant first read the list of words to the learner and then began testing him on his learning. The shock apparatus (Figure 14.7) was in front of the teacher, and the learner was not visible in the shock room. The experimenter sat behind the teacher and explained to him that each time the learner made a mistake he was to press one of the shock switches to administer the shock. Moreover, the switch that was to be pressed increased by one level with each mistake, so that each mistake required a stronger shock.

Once the learner (who was, of course, actually the experimental confederate) was alone in the shock room, he unstrapped himself from the shock machine and brought out a tape recorder that he used to play a prerecorded series of responses that the teacher c ould hear through the wall of the room.

The teacher heard the learner say “ugh!” after the first few shocks. After the next few mistakes, when the shock level reached 150 V, the learner was heard to exclaim, “Let me out of here. I have heart trouble!” As the shock reached about 270 V, the protests of the learner became more vehement, and after 300 V the learner proclaimed that he was not going to answer any more questions. From 330 V and up, the learner was silent. At this point the experimenter responded to participants’ questions, if any, with a scripted response indicating that they should continue reading the questions and applying increasing shock when the learner did not respond.

The results of Milgram’s research were themselves quite shocking. Although all the participants gave the initial mild levels of shock, responses varied after that. Some refused to continue af ter about 150 V, despite the insistence of the experimenter to continue to increase the shock level. Still others, however, continued to present the questions and to administer the shocks, under the pressure of the experimenter, who demanded that they continue. In the end, 65% of the participants continued giving the shock to the learner all the way up to the 450 V maximum, even though that shock was marked as “danger: severe shock” and no response had been heard from the participant for several trials. In other words, well over half of the men who participated had, as far as they knew, shocked another person to death, all as part of a supposed experiment on learning.

In case you are thinking that such high levels of obedience would not be observed in today’s modern culture, there is fact evidence that they would. Milgram’s findings were almost exactly replicated, using men and women from a wide variety of e thnic groups, in a study conducted this decade at Santa Clara University (Burger, 2009). 2 In this replication of the Milgram experiment, 67% of the men and 73% of the women agreed to administer increasingly painful electric shocks when an authority figure ordered them to. The participants in this study were not, however, allowed to go beyond the 150 V shock switch.

Although it might be tempting to conclude that Burger’s and Milgram’s experiments demonstrate that people are innately bad creatures who are ready to shock others to death, this is not in fact the case. Rather it is the social situation, and not the people themselves, that is responsible for the behavior. When Milgram created variations on his original procedure, he found that changes in the situation dramatically influenced the amount of conformity. Conformity was significantly reduced when people were allowed to choose their own shock level rather than being ordered to use the level required by the experimenter, when the experimenter communicated by phone rather than from within the experimental room, and when other research participants refused to give the shock. These findings are consistent with a basic principle of social psychology: The situation in which people find themselves has a major influence on their behavior.

- 2453 reads