Anyone who has tried to master a second language a s an adult knows the difficulty of language learning. And yet children learn languages easily and naturally. Children who are not exposed to language early in their lives will likely never learn one. Case studies, including Victor the “Wild Child,” who was abandoned as a baby in France and not discovered until he was 12, and Genie, a child whose parents kept her locked in a closet from 18 months until 13 years of age, are (fortunately) two of the only known examples of these deprived children. Both of these children made some progress in socialization after they were rescued, but neither of them ever developed language (Rymer, 1993). 1 This is also why it is important to determine quickly if a child is deaf and to begin immediately to communicate in sign language. Deaf children who are not exposed to sign language during their early years will likely never learn it (Mayberry, Lock, & Kazmi, 2002). 2

Research Focus: When Can We Best Learn Language? Testing the Critical Period Hypothesis

For many years psychologists assumed that there was a critical period (a time in which learning can easily occur) for language learning, lasting between infancy and puberty, and after which language learning was more difficult or impossible (Lenneberg, 1967; Penfield & Roberts, 1959). 3 But more recent research has provided a different interpretation.

An important study by Jacqueline Johnson and Elissa Newport (1989) 4 using Chinese and Korean speakers who had learned English as a second language provided the first insight. The participants were all adults who had immigrated to the United States between 3 and 39 years of age and who were tested on their English skills by being asked to detect grammatical errors in sentences. Johnson and Newport found that the participants who had begun learning English before they were 7 years old learned it as well as native English speakers but that the ability to learn English dropped off gradually for the participants who had started later. Newport and Johnson also found a correlation between the age of acquisition and the variance in the ultimate learning of the language. While early learners were almost all successful in acquiring their language to a high degree of proficiency, later learners showed much greater individual variation.

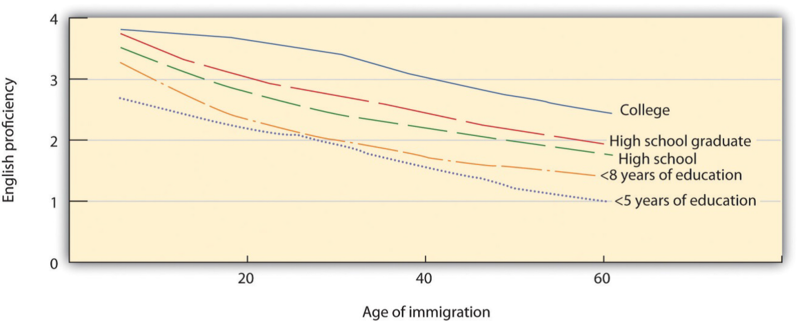

Johnson and Newport’s finding that children who immigrated before they were 7 years old learned English fluently seemed consistent with the idea of a “critical period” in language learning. But their finding of a gradual decrease in proficiency for those who immigrated between 8 and 39 years of age was not—rather, it suggested that there might not be a single critical period of language learning that ended at puberty, as early theorists had expected, but that language learning at later ages is simply better when it occurs earlier. This idea was reinforced in research by Hakuta, Bialystok, and Wiley (2003), 5 who examined U.S. census records of language learning in millions of Chinese and Spanish speakers living in the United States. The census form asks respondents to describe their own English ability using one of five categories: “not at all,” “not well,” “well,” “very well,” and “speak only English.” The results of this research dealt another blow to the idea of the critical period, because it showed that regardless of what year was used as a cutoff point for the end of the critical period, there was no evidence for any discontinuity in language-learning potential. Rather, the results (Figure 9.7) showed that the degree of success in second-language acquisition declined steadily throughout the respondent’s life span. The difficulty of learning language as one gets older is probably due to the fact that, with age, the brain loses its plasticity—that is, its ability to develop new neural connections.

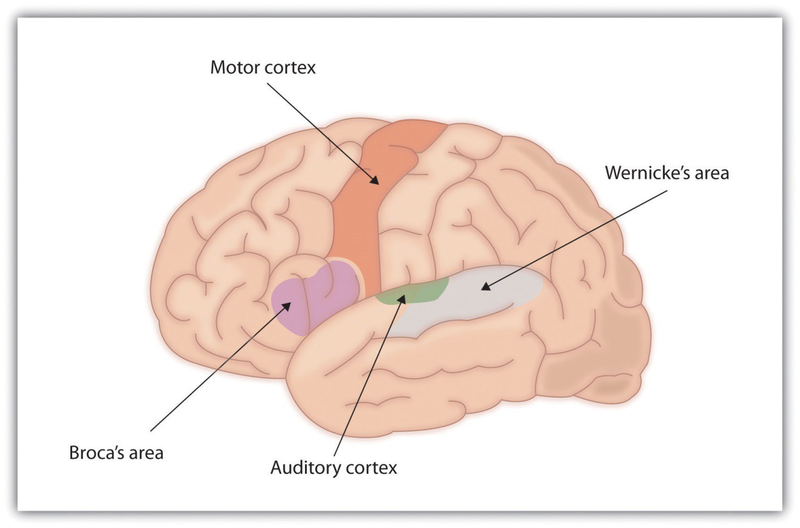

For the 90% of people who are right-handed, language is stored and controlled by the left cerebral cortex, although for some left-handers this pattern is reversed. These differences can easily be seen in the results of neuroimaging studies that show that listening to and producing language creates greater activity in the left hemisphere than in the right. Broca’s area, an area in front of theleft hemispherenear themotor cortex, is responsible for language production (Figure 9.8). This area was first localized in the 1860s by the French physician Paul Broca, who studied patients with lesions to various parts of the brain.Wernicke’s area, an area of thebrain next to theauditory cortex, is responsible for language comprehension.

language.Broca’sarea, near the motor cortex, is involved in language production,whereas Wernicke’s area, near the auditory cortex, is specialized for language comprehension.

Evidence for the importance of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas in language is seen in patients who experience aphasia, a condition in which languagefunctions areseverelyimpaired. People with Broca’s aphasia have difficulty producing speech, whereas people with damage to Wernicke’s area can produce speech, but what they say makes no sense and they have trouble understanding language.

- 3504 reads