Psychologists have developed criteria that help them determine whether behavior should be considered a psychological disorder and which of the many disorders particular behaviors indicate. These criteria are laid out in a 1,000-page manual known as theDiagnostic a nd Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a document that provides a common languageand standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). 1 The DSMis used by therapists, researchers, drug companies, health insurance companies, and policymakers in the United States to determine what services are appropriately provided for treating patients with given symptoms.

The first edition of the DSMwas published in 1952 on the basis of ce nsus data and psychiatric hospital statistics. Since then, the DSMhas been revised five times. The last major revision was the fourth edition (DSM-IV), published in 1994, and an update of that document was produced in 2000 (DSM-IV-TR). The fifth edition (DSM-V) is currently undergoing review, planning, and preparation and is scheduled to be published in 2013. The DSM-IV-TR was designed in conjunction with the World Health Organization’s 10th version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which is used as a guide for mental disorders in Europe and other parts of the world.

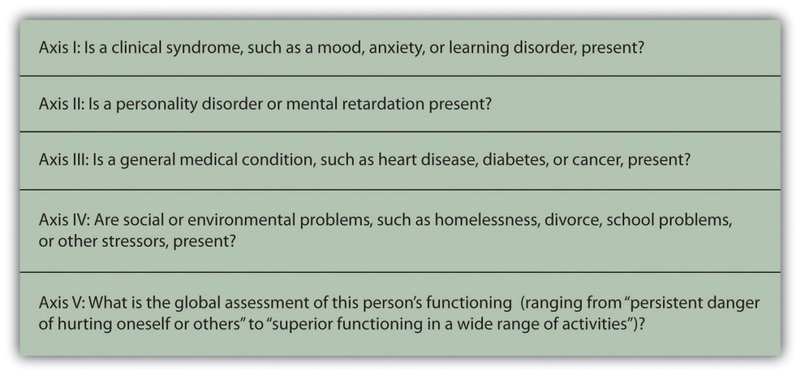

As you can see in Figure 12.3, the DSM organizes the diagnosis of disorder according to five dimensions (or axes) relating to different aspects of disorder or disability. The axes are important to remember when we think about psychological disorder, because they make it clear not only that there are different types of disorder, but that those disorders have a variety of different causes. Axis Iincludes the most usual clinical disorders, including mood disorders and anxietydisorders; Axis IIincludes the less severe but long-lasting personalitydisorders as well as mental retardation; Axis IIIand Axis IV relate to physical symptoms and social-cultural factors, respectively. The axes remind us that when making a diagnosis we must look at the complete picture, including biological, personal, and social-cultural factors.

The DSM does not attempt to specify the exact symptoms that are required for a diagnosis. Rather, the DSM uses categories, and patients whose symptoms are similar to the description of the category are said to have that disorder. TheDSM frequently uses qualifiers to indicate different levels of severity within a category. For instance, the disorder of mental retardation can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Each revision of the DSMtakes into consideration new knowledge as well as changes in cultural norms about disorder. Homosexuality, for example, was listed as a mental disorder in the DSM until 1973, when it was removed in response to advocacy by politically active gay rights groups and changing social norms. The current version of the DSM lists about 400 disorders. Some of the major categories are shown in Table 12.3, and you may go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DSM- IV_Codes_(alphabetical) and browse the complete list.

|

Categoryanddescription |

Examples |

|

Disorders diagnosed in infancy and childhood |

Mental retardation |

|

Communication, conduct, elimination, feeding, learning, and motor skills disorders |

|

|

Autism spectrum disorders |

|

|

Attention-deficit and disruptive behavior disorders including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

|

|

Separation anxiety disorder |

|

|

Delirium, dementia, and amnesia (forgetting or memory distortions caused by physical factors) |

Delirium |

|

Dementia and Alzheimer disease |

|

|

Dissociative disorders (forgetting or memory distortions that do not involve physical factors) |

Dissociative amnesia |

|

Dissociative fugue |

|

|

Dissociative identity disorder (“multiple personality”) |

|

|

Substance abuse disorders |

Alcohol abuse |

|

Drug abuse |

|

|

Caffeine abuse |

|

|

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders |

|

|

Mood disorders |

Mood disorder |

|

Major depressive disorder |

|

|

Bipolar disorder |

|

|

Anxiety disorders |

Generalized anxiety disorder |

|

Panic disorder |

|

|

Specific phobia including agoraphobia |

|

|

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) |

|

|

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

|

|

Somatoform disorders (physical symptoms that do not have a clear physical cause and thus must be psychological in origin) |

Conversion disorder |

|

Pain disorder |

|

|

Hypochondriasis |

|

|

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) |

|

|

Factitious disorders (conditions in which a person acts as if he or she has an illness by deliberately producing, feigning, or exaggerating symptoms) |

|

|

Sexual disorders |

Sexual dysfunctions including erectile and orgasmic disorders |

|

Paraphilias |

|

|

Gender identity disorders |

|

|

Sexual abuse |

|

|

Eating disorders |

Anorexia nervosa |

|

Bulimia nervosa |

|

|

Sleep disorders |

Narcolepsy |

|

Sleep apnea |

|

|

Impulse-control disorders |

Kleptomania (stealing) |

|

Pyromania (fire lighting) |

|

|

Pathological gambling (addiction) |

|

|

Personality disorders |

|

|

Cluster A (odd or eccentric behaviors) |

Paranoid personality disorder |

|

Schizoid personality disorder |

|

|

Schizotypal personality disorder |

|

|

Cluster B (dramatic, emotional, or erratic behaviors) |

Antisocial personality disorder |

|

Borderline personality disorder |

|

|

Histrionic personality disorder |

|

|

Narcissistic personality disorder |

|

|

Cluster C (anxious or fearful behaviors) |

Avoidant personality disorder |

|

Dependent personality disorder |

|

|

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder |

|

|

Other disorders |

Includes academic problems, antisocial behavior, bereavement, child neglect, occupational problems, relational problems, physical abuse, and malingering |

Although the DSMhas been criticized regarding the nature of its categorization system (and it is frequently revised to attempt to address these criticisms), for the fact that it tends to classify more behaviors as disorders with every revision (even “academic problems” are now listed as a potential psychological disorder), and for the fact that it is primarily focused on Western illness, it is nevertheless a comprehensive, practical, and necessary tool that provides a common language to describe disorder. Most U.S. insurance companies will not pay for therapy unless the patient has a DSMdiagnosis. The DSM approach allows a systematic assessment of the patient, taking into account the mental disorder in question, the patient’s medical condition, psychological and cultural factors, and the way the patient functions in everyday life.

- 5122 reads