As we have seen in our earlier discussion, accommodation (i.e., the changing of beliefs on the basis of new information) does occur; indeed it is the process of learning itself. For example, your belief about Italians may well change through your encounters with Bianca. However, there are many factors that lead us to assimilate information into our expectations rather than to accommodate our expectations to fit new information. In fact, we can say that in most cases, once a schema is developed, it will be difficult to change it because the expectation leads us to process new information in ways that serve to strengthen it rather than to weaken it.

The tendency toward assimilation is so strong that it has substantial effects on our everyday social cognition. One outcome of assimilation is the confirmation bias, the tendency for people to seek out and favor information that confirms their expectations and beliefs, which in turn can further help to explain the often self-fulfilling nature of our schemas. The confirmation bias has been shown to occur in many contexts and groups, although there is some evidence of cultural differences in its extent and prevalence. Kastenmuller and colleagues (2010), for instance, found that the bias was stronger among people with individualist versus collectivist cultural backgrounds, and argued that this partly stemmed from collectivist cultures putting greater importance in being self-critical, which is less compatible with seeking out confirming as opposed to disconfirming evidence.

Research Focus: The Confirmation Bias

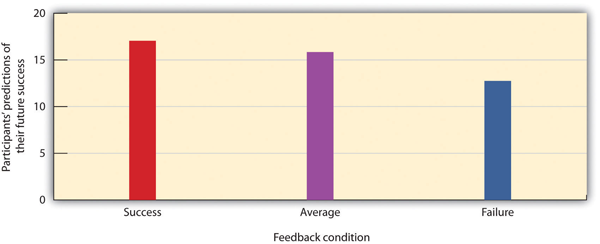

Consider the results of a research study conducted by Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975) that demonstrated the confirmation bias. In this research, high school students were asked to read a set

of 25 pairs of cards, in which each pair supposedly contained one real and one fake suicide note. The students’ task was to examine both cards and to decide which of the two notes was written

by an actual suicide victim. After the participants read each card and made their decision, the experimenter told them whether their decision was correct or incorrect. However, the feedback

was not at all based on the participants’ responses. Rather, the experimenters arranged the feedback so that, on the basis of random assignment, different participants were told either that

they were successful at the task (they got 24 out of 25 correct), average at the task (they got 17 out of 25 correct), or poor at the task (they got 10 out of 25 correct), regardless of their

actual choices. At this point, the experimenters stopped the experiment and explained to the participants what had happened, including how the feedback they had received was predetermined so

that they would learn that they were either successful, average, or poor at the task. They were even shown the schedule that the experimenters had used to give them the feedback. Then the

participants were asked, as a check on their reactions to the experiment, to indicate how many answers they thought they would get correct on a subsequent—and real—series of 25 card pairs. As

you can see in Figure 2.7, the results of

this experiment showed a clear tendency for expectations to be maintained even in the face of information that should have discredited them. Students who had been told that they were

successful at the task indicated that they thought they would get more responses correct in a real test of their ability than those who thought they were average at the task, and students who

thought they were average thought they would do better than those told they were poor at the task. In short, once students had been convinced that they were either good or bad at the task,

they really believed it. It then became very difficult to remove their beliefs, even by providing information that should have effectively done so.

Why do we tend to hold onto our beliefs rather than change them? One reason that our beliefs often outlive the evidence on which they are supposed to be based is that people come up with reasons to support their beliefs. People who learned that they were good at detecting real suicide notes probably thought of a lot of reasons why this might be the case—“I predicted that Suzy would break up with Billy,” or “I knew that my mother was going to be sad after I left for university”—whereas the people who learned that they were not good at the task probably thought of the opposite types of reasons—“I had no idea that Jean was going to drop out of high school.” You can see that these tendencies will produce assimilation—the interpretation of our experiences in ways that support our existing beliefs. Indeed, research has found that perhaps the only way to reduce our tendencies to assimilate information into our existing belief is to explicitly force people to think about exactly the opposite belief (Anderson & Sechler, 1986). In some cases, our existing knowledge acts to direct our attention toward information that matches our expectations and prevents us from attempting to attend to or acknowledge conflicting information (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). To return to our example of Bianca from Rome, when you first meet her, you may immediately begin to look for signs of expressiveness in her behavior and personality. Because we expect people to confirm our expectations, we frequently respond to new people as if we already know what they are going to be like. For example, Trope and Thompson (1997) found in their research that individuals addressed fewer questions to people about whom they already had strong expectations and that the questions they did ask were likely to confirm the expectations they already had. If you believe that Italians are expressive, you would expect to see that behavior in Bianca, you would preferentially attend to information that confirms those beliefs, and you would tend to ignore any disconfirming information. The outcome is that expectations resist change (Fazio, Ledbetter, & Towles-Schwen, 2000).

Not only do we often seek out evidence more readily if it fits our pre-existing beliefs, but we also tend to evaluate its credibility more favorably than we do evidence that runs against what we believe (Stanovich, West, & Toplak, 2013). These tendencies in turn help to explain the inertia that our beliefs often display, and their resistance to contradictory evidence, even when they are inaccurate or dysfuntional.

Applying these insights to the case study that opened this chapter, perhaps the financial meltdown of 2008 was caused in part by key decision-makers continuing with high-risk investment strategies, even in the face of growing evidence of the potential negative consequences. Seen through the lens of the confirmation bias, these judgments start to make sense. Confirmation bias can lead investors to be overconfident, ignoring evidence that their strategies will lose money (Kida, 2006). It seems, then, that too much effort was spent on finding evidence confirming the wisdom of the current strategies and not enough time was allocated to finding the counterevidence.

Our reliance on confirmatory thinking can also make it more difficult for us to “think outside the box.” Peter Wason (1960) asked college students to determine the rule that was used to generate the numbers 2-4-6 by asking them to generate possible sequences and then telling them if those numbers followed the rule. The first guess that students made was usually “consecutive ascending even numbers,” and they then asked questions designed to confirm their hypothesis (“Does 102-104-106 fit?” “What about 434-436-438?”). Upon receiving information that those guesses did fit the rule, the students stated that the rule was “consecutive ascending even numbers.” But the students’ use of the confirmation bias led them to ask only about instances that confirmed their hypothesis and not about those that would disconfirm it. They never bothered to ask whether 1-2-3 or 3-11-200 would fit; if they had, they would have learned that the rule was not “consecutive ascending even numbers” but simply “any three ascending numbers.” Again, you can see that once we have a schema (in this case, a hypothesis), we continually retrieve that schema from memory rather than other relevant ones, leading us to act in ways that tend to confirm our beliefs.

Because expectations influence what we attend to, they also influence what we remember. One frequent outcome is that information that confirms our expectations is more easily processed and understood, and thus has a bigger impact than does disconfirming information. There is substantial research evidence indicating that when processing information about social groups, individuals tend to remember information better that confirms their existing beliefs about those groups (Fyock & Stangor, 1994; Van Knippenberg & Dijksterhuis, 1996). If we have the (statistically erroneous) stereotype that women are bad drivers, we tend to remember the cases where we see a woman driving poorly but to forget the cases where we see a woman driving well. This of course strengthens and maintains our beliefs and produces even more assimilation. And our schemas may also be maintained because when people get together, they talk about other people in ways that tend to express and confirm existing beliefs, including stereotypes (Ruscher & Duval, 1998; Schaller & Conway, 1999).

Darley and Gross (1983) demonstrated how schemas about social class could influence memory. In their research, they gave participants a picture and some information about a girl in grade 4, named Hannah. To activate a schema about her social class, Hannah was pictured sitting in front of a nice suburban house for one half of the participants and in front of an impoverished house in an urban area for the other half. Then the participants watched a video that showed Hannah taking an intelligence test. As the test went on, Hannah got some of the questions right and some of them wrong, but the number of correct and incorrect answers was the same in both conditions. Then the participants were asked to remember how many questions Hannah got right and wrong. Demonstrating that stereotypes had influenced memory, the participants who thought that Hannah had come from an upper-class background judged that she had gotten more correct answers than those who thought she was from a lower-class background. It seems, then, that we have a reconstructive memory bias, as we often remember things that match our current beliefs better than those that don’t and reshape those memories to better align with our current beliefs (Hilsabeck, Gouvier, & Bolter, 1998).

This is not to say that we only remember information that matches our expectations. Sometimes we encounter information that is so extreme and so conflicting with our expectations that we cannot help but attend to and remember it (Srull & Wyer, 1989). Imagine that you have formed an impression of a good friend of yours as a very honest person. One day you discover, however, that he has taken some money from your wallet without getting your permission or even telling you. It is likely that this new information—because it is so personally involving and important—will have a dramatic effect on your perception of your friend and that you will remember it for a long time. In short, information that is either consistent with, or very inconsistent with, an existing schema or attitude is likely to be well remembered.

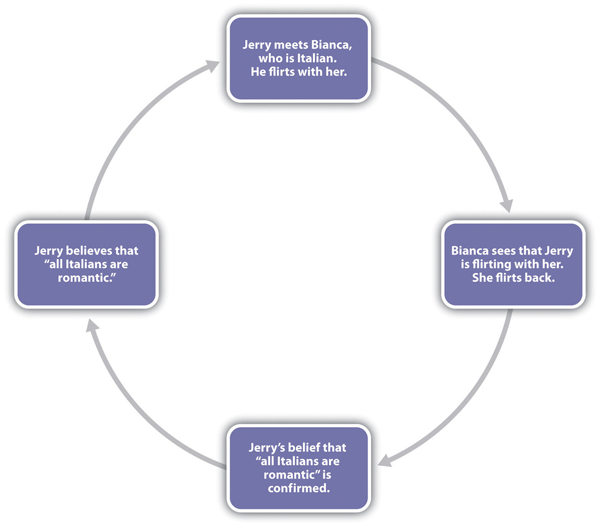

Still another way that our expectations tend to maintain themselves is by leading us to act toward others on the basis of our expectations, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. A self-fulfilling prophecy is a process that occurs when our expectations about others lead us to behave toward those others in ways that make our expectations come true. If I have a stereotype that Italians are friendly, then I may act toward Bianca in a friendly way. My friendly behavior may be reciprocated by Bianca, and if many other people also engage in the same positive behaviors with her, in the long run she may actually become a friendlier person, thus confirming my initial expectations. Of course, the opposite is also possible—if I believe that Italian people are boring, my behavior toward them may lead me to maintain those more negative, and probably inaccurate, beliefs as well (Figure 2.8).

We can now begin to see why an individual who initially makes a judgment that a person has engaged in a given behavior (e.g., an eyewitness who believes that he or she saw a given person commit a crime) will find it very difficult to change his or her mind about that decision later. Even if the individual is provided with evidence that suggests that he or she was wrong, that individual will likely assimilate that information to the existing belief. Assimilation is thus one of many factors that help account for the inaccuracy of eyewitness testimony.

Research Focus: Schemas as Energy Savers

If schemas serve in part to help us make sense of the world around us, then we should be particularly likely to use them in situations where there is a lot of information to learn about, or when we have few cognitive resources available to process information. Schemas function like energy savers, to help us keep track of things when information processing gets complicated. Stangor and Duan (1991) tested the hypothesis that people would be more likely to develop schemas when they had a lot of information to learn about. In the research, participants were shown information describing the behaviors of people who supposedly belonged to different social groups, although the groups were actually fictitious and were labeled only as the “red group,” the “blue group,” the “yellow group,” and the “green group.” Each group engaged in behaviors that were primarily either honest, dishonest, intelligent, or unintelligent. Then, after they had read about the groups, the participants were asked to judge the groups and to recall as much information that they had read about them as they could. Stangor and Duan found that participants remembered more stereotype-supporting information about the groups when they were required to learn about four different groups than when they only needed to learn about one or two groups. This result is consistent with the idea that we use our stereotypes more when “the going gets rough”—that is, when we need to rely on them to help us make sense of new information.

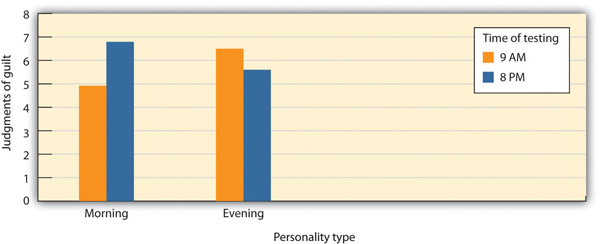

Bodenhausen (1990) presented research participants with information about court cases in jury trials. Furthermore, he had obtained self-reports from the participants about whether they considered themselves to be primarily “morning people” (those who feel better and are more alert in the morning) or “evening people” (those who are more alert in the evening). As shown in Figure 2.9, Bodenhausen found that participants were more likely to make use of their stereotypes when they were judging the guilt or innocence of the individuals on trial at the time of day when the participants acknowledged that they were normally more fatigued. People who reported being most alert in the morning stereotyped more at night, and vice versa. This experiment thus provides more support for the idea that schemas—in this case, those about social groups—serve, in part, to make our lives easier and that we rely on them when we need to rely on cognitive efficiency—for instance, when we are tired.

Key Takeaways

- Human beings respond to the social challenges they face by relying on their substantial cognitive capacities.

- Our knowledge about and our responses to social events are developed and influenced by operant learning, associational learning, and observational learning.

- One outcome of our experiences is the development of mental representations about our environments—schemas and attitudes. Once they have developed, our schemas influence our subsequent learning, such that the new people and situations we encounter are interpreted and understood in terms of our existing knowledge.

- Accommodation occurs when existing schemas change on the basis of new information. Assimilation occurs when our knowledge acts to influence new information in a way that makes the conflicting information fit with our existing schemas.

- Because our expectations influence our attention and responses to, and our memory for, new information, often in a way that leads our expectations to be maintained, assimilation is generally more likely than accommodation.

- Schemas serve as energy savers. We are particularly likely to use them when we are tired or when the situation that we must analyze is complex.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Describe a time when you learned new social information or new behaviors through operant, associational, or observational learning.

- Think about a time when you made a snap judgment about another person. How did your expectations about people influence your judgment of this person? Looking back on this, to what extent do you think that the judgment fair or unfair?

- Consider some of your beliefs about the people you know. Were these beliefs formed through assimilation, accommodation, or a combination of both? To what degree do you think that your expectations now influence how you respond to these people?

- Describe a time when you had a strong expectation about another person’s likely behavior. In what ways and to what extent did that expectation serve as an energy saver?

References

Akers, R. L. (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Anderson, C. A., & Sechler, E. S. (1986). Effects of explanation and counterexplanation on the development and use of social theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(1), 24–34.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1959). Adolescent aggression. New York, NY: Ronald Press.

Bodenhausen, G. V. (1990). Stereotypes as judgmental heuristics: Evidence of circadian variations in discrimination. Psychological Science, 1, 319–322.

Darley, J. M., & Gross, P. H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20–33.

Das, E. H. H. J., de Wit, J. B. F., & Stroebe, W. (2003). Fear appeals motivate acceptance of action recommendations: Evidence for a positive bias in the processing of persuasive messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(5), 650–664.

Fazio, R. H., Ledbetter, J. E., & Towles-Schwen, T. (2000). On the costs of accessible attitudes: Detecting that the attitude object has changed. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 197–210.

Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from category based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 1–74). New York, NY: Academic.

Fyock, J., & Stangor, C. (1994). The role of memory biases in stereotype maintenance. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 331–343.

Gorn, G. J. (1982). The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: A classical conditioning approach. Journal of Marketing, 46(1), 94–101.

Hawkins, D., Best, R., & Coney, K. (1998.) Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy (7th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill

Hilsabeck, R. C., Gouvier, W., & Bolter, J. F. (1998). Reconstructive memory bias in recall of neuropsychological symptomatology. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 20(3), 328-338 doi:10.1076/jcen.20.3.328.813

Kastenmuller, A., Greitemeyer, T., Jonas, E., Fischer, P., & Frey. D. (2010). Selective exposure: The impact of individualism and collectivism. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 745-763.

Kida, Thomas E. (2006), Don’t believe everything you think: the 6 basic mistakes we make in thinking, Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). Damage to the prefontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature, 446(7138), 908–911.

Lamb, C. S., & Crano, W. D. (2014). Parent’s beliefs and children’s marijuana use: Evidence for a self-fulfilling prophecy effect. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 127-132.

Lewicki, P. (1985). Nonconscious biasing effects of single instances on subsequent judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 563–574.

Mae, L., & Carlston, D. E. (2005). Hoist on your own petard: When prejudiced remarks are recognized and backfire on speakers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(3), 240–255.

Mitchell, J. P., Mason, M. F., Macrae, C. N., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). Thinking about others: The neural substrates of social cognition. In J. T. Cacioppo, P. S. Visser, & C. L. Pickett (Eds.), Social neuroscience: People thinking about thinking people (pp. 63–82). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Piaget, J., and Inhelder, B. (1962). The psychology of the child. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception: Biased attributional processes in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 32, 880–892.

Ruscher, J. B., & Duval, L. L. (1998). Multiple communicators with unique target information transmit less stereotypical impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 329–344.

Schaller, M., & Conway, G. (1999). Influence of impression-management goals on the emerging content of group stereotypes: Support for a social-evolutionary perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 819–833.

Schemer, C., Matthes, J. R., Wirth, W., & Textor, S. (2008). Does “passing the Courvoisier” always pay off? Positive and negative evaluative conditioning effects of brand placements in music videos. Psychology & Marketing, 25(10), 923–943.

Sigall, H., & Landy, D. (1973). Radiating beauty: Effects of having a physically attractive partner on person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(2), 218–224.

Skowronski, J. J., Carlston, D. E., Mae, L., & Crawford, M. T. (1998). Spontaneous trait transference: Communicators take on the qualities they describe in others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 837–848.

Srull, T., & Wyer, R. (1989). Person memory and judgment. Psychological Review, 96(1), 58–83.

Stangor, C., & Duan, C. (1991). Effects of multiple task demands upon memory for information about social groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27, 357–378.

Stanovich, K. E., West, R. F., & Toplak, M. E. (2013). Myside bias, rational thinking, and intelligence. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 22(4), 259-264. doi:10.1177/0963721413480174

Tambling, R. B. (2012). A literature review of expectancy effects. Contemporary Family Therapy, 34(3), 402-415.

Taylor, S. E., & Crocker, J. (1981). Schematic bases of social information processing. In E. T. Higgins, C. P. Herman, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Social cognition: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 1, pp. 89–134). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Van Knippenberg, A., & Dijksterhuis, A. (1996). A posteriori sterotype activation: The preservation of sterotypes through memory distortion. Social Cognition, 14, 21–54.

Wason, P. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140.

Wurm, S. W., Ziegelmann, L. M., Wolff, J. K., & Schuz, B. (2013). How do negative self-perceptions of aging become a self-fulfilling prophecy? Psychology and Aging, 28(4), 1088-1097.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615.

- 15313 reads