Causal attribution is involved in many important situations in our lives; for example, when we attempt to determine why we or others have succeeded or failed at a task. Think back for a moment to a test that you took, or another task that you performed, and consider why you did either well or poorly on it. Then see if your thoughts reflect what Bernard Weiner (1985) considered to be the important factors in this regard.

Weiner was interested in how we determine the causes of success or failure because he felt that this information was particularly important for us: accurately determining why we have succeeded or failed will help us see which tasks we are good at already and which we need to work on in order to improve. Weiner proposed that we make these determinations by engaging in causal attribution and that the outcomes of our decision-making process were attributions made either to the person (“I succeeded/failed because of my own personal characteristics”) or to the situation (“I succeeded/failed because of something about the situation”).

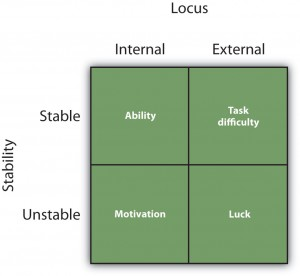

Weiner’s analysis is shown in Figure 5.8. According to Weiner, success or failure can be seen as coming from personal causes (e.g., ability, motivation) or from situational causes (e.g., luck, task difficulty). However, he also argued that those personal and situational causes could be either stable (less likely to change over time) or unstable (more likely to change over time).

This figure shows the potential attributions that we can make for our, or for other people’s, success or failure. Locus considers whether the attributions are to the person or to the situation, and stability considers whether or not the situation is likely to remain the same over time.

If you did well on a test because you are really smart, then this is a personal and stable attribution of ability. It’s clearly something that is caused by you personally, and it is also quite a stable cause—you are smart today, and you’ll probably be smart in the future. However, if you succeeded more because you studied hard, then this is a success due to motivation. It is again personal (you studied), but it is also potentially unstable (although you studied really hard for this test, you might not work so hard for the next one). Weiner considered task difficulty to be a situational cause: you may have succeeded on the test because it was easy, and he assumed that the next test would probably be easy for you too (i.e., that the task, whatever it is, is always either hard or easy). Finally, Weiner considered success due to luck (you just guessed a lot of the answers correctly) to be a situational cause, but one that was more unstable than task difficulty. It turns out that although Weiner’s attributions do not always fit perfectly (e.g., task difficulty may sometimes change over time and thus be at least somewhat unstable), the four types of information pretty well capture the types of attributions that people make for success and failure.

We have reviewed some of the important theory and research into how we make attributions. Another important question, that we will now turn to, is how accurately we attribute the causes of behavior. It is one thing to believe that that someone shouted at us because he or she has an aggressive personality, but quite another to prove that the situation, including our own behavior, was not the more important cause!

Key Takeaways

- Causal attribution is the process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior.

- Attributions are made to personal or situational causes.

- It is easier to make personal attributions when a behavior is unusual or unexpected and when people are perceived to have chosen to engage in it.

- The covariation principle proposes that we use consistency information, distinctiveness information, and consensus information to draw inferences about the causes of behaviors.

- According to Bernard Weiner, success or failure can be seen as coming from either personal causes (ability and motivation) or situational causes (luck and task difficulty).

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Describe a time when you used causal attribution to make an inference about another person’s personality. What was the outcome of the attributional process? To what extent do you think that the attribution was accurate? Why?

- Outline a situation where you used consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness information to make an attribution about someone’s behavior. How well does the covariation principle explain the type of attribution (internal or external) that you made?

- Consider a time when you made an attribution about your own success or failure. How did your analysis of the situation relate to Weiner’s ideas about these processes? How did you feel about yourself after making this attribution and why?

References

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1985b). The group attribution error. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21(6), 563-579.

Campbell, W. K., Sedikides, C., Reeder, G. D., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Among friends: An examination of friendship and the self-serving bias. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 229-239.

Cheng, P. W., & Novick, L. R. (1990). A probabilistic contrast model of causal induction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 545–567.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jones, E. E., & Harris, V. A. (1967). The attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3(1), 1–24.

Jones, E. E., Davis, K. E., & Gergen, K. J. (1961). Role playing variations and their informational value for person perception. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(2), 302–310.

Jones, E. E., Kanouse, D. E., Kelley, H. H., Nisbett, R. E., Valins, S., & Weiner, B. (Eds.). (1987). Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kassin, S. M. (1979). Consensus information, prediction, and causal attribution: A review of the literature and issues. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 37, 1966-1981.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 15, pp. 192–240). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Lyon, H. M., & Startup, M., & Bentall, R. P. (1999). Social cognition and the manic defense: Attributions, selective attention, and self-schema in Bipolar Affective Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2), 273-282.Frubin

Uleman, J. S., Blader, S. L., & Todorov, A. (Eds.). (2005). Implicit impressions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Weiner, B. (1985). Attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548–573.

- 23823 reads